The base map is provided by OpenTopoMap’s volunteer servers.

Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

___ Glacial Features

___ Rock Exposure Ages Determined by Cosmogenic Isotope Dating

___ Complications of Beryllium-10 Dating

___ Exposure Ages of Pinedale Moraines

___ Exposure Age of “Titcomb Lakes” Moraine

___ Exposure Ages of “Temple Lake” and “Alice Lake” Moraines

___ Exposure Ages of Glacier Retreat East of the Continental Divide

___ Exposure Ages of Moraines in Stough Creek Basin

___ Little Ice Age Glaciation

___ Summary of Pond History

Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

___ What Is Fish-stocking?

___ Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

___ How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

___ How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Wind River Mountains?

___ If the stocked fish die without establishing a reproducing population, can previously eliminated invertebrate species recover?

___ What happens when fish become residents of a previously fishless lake in the Wind River Mountains?

___ What experimental evidence can be used to determine the effects of fish-stocking on fairy shrimp?

___ What other experiments with fish and invertebrates can be used to infer what happened to fairy shrimp in stocked lakes?

___ Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

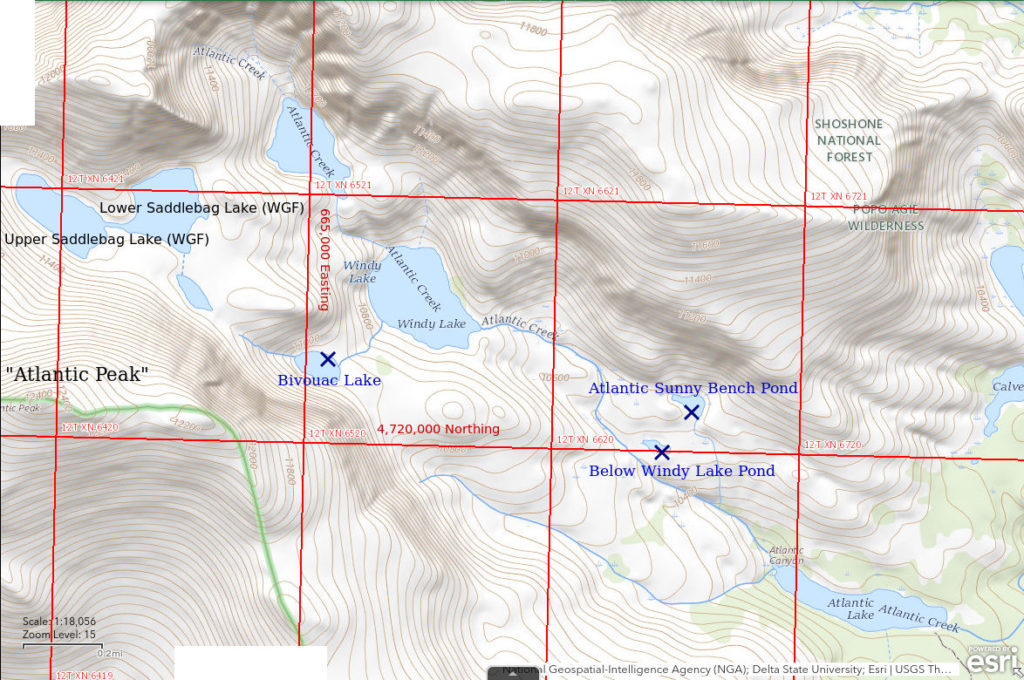

Bivouac Lake

Atlantic Sunny Bench Pond

Below “Windy Lake” Pond

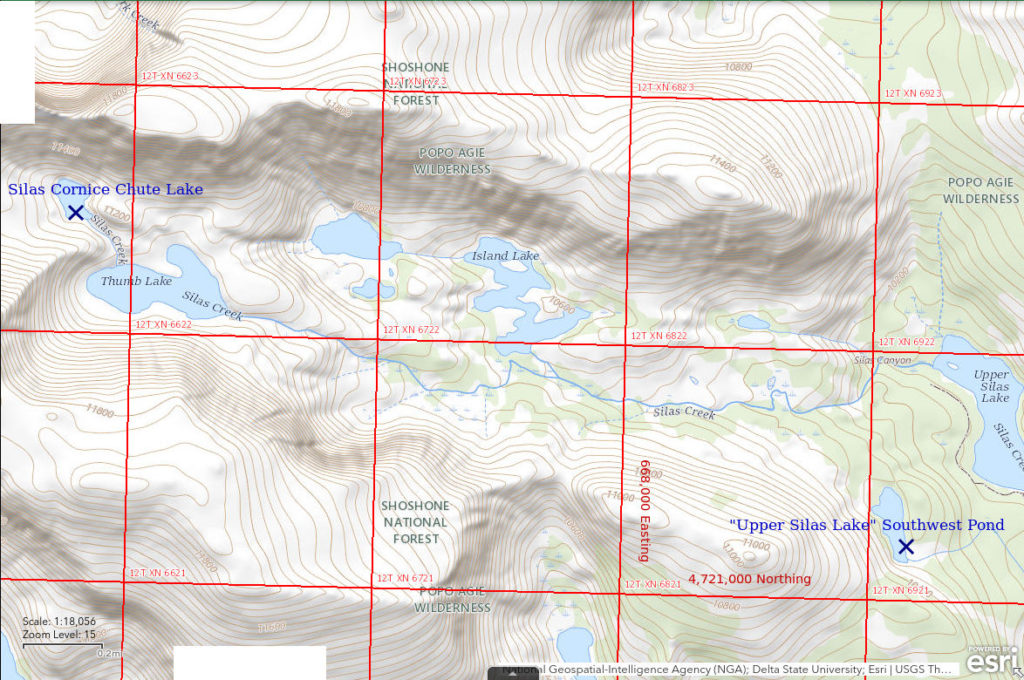

“Upper Silas Lake” Southwest Pond

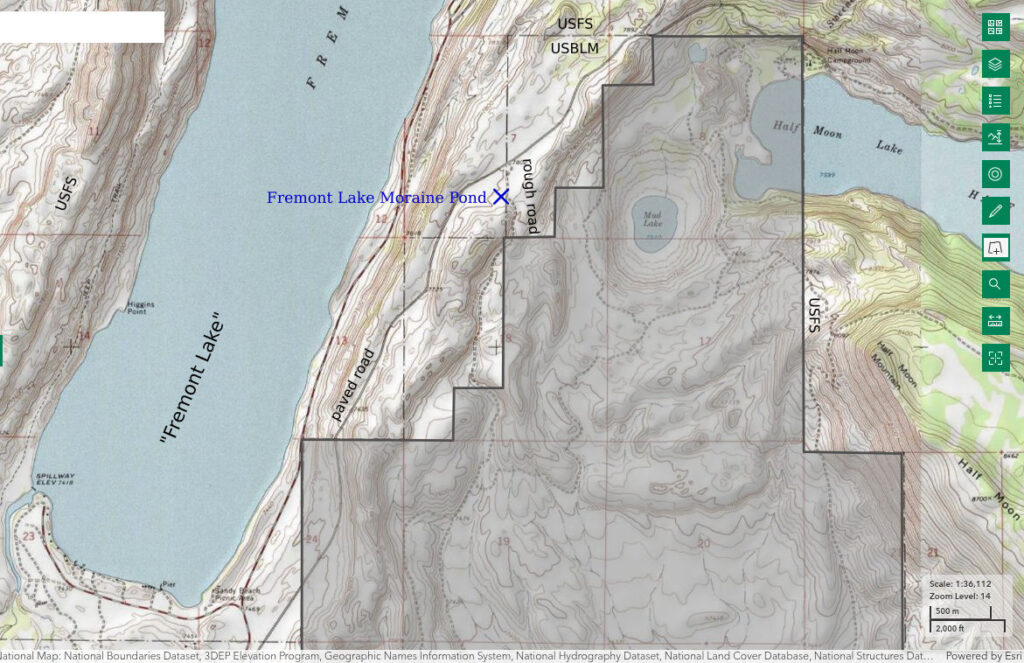

“Fremont Lake” Moraine Pond

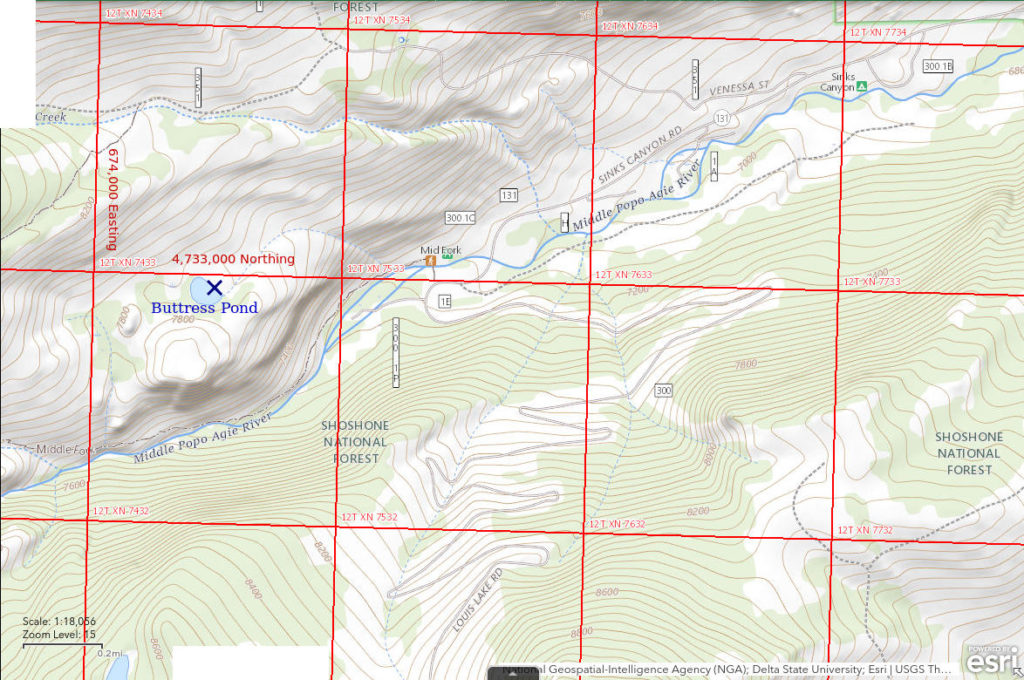

Buttress Pond

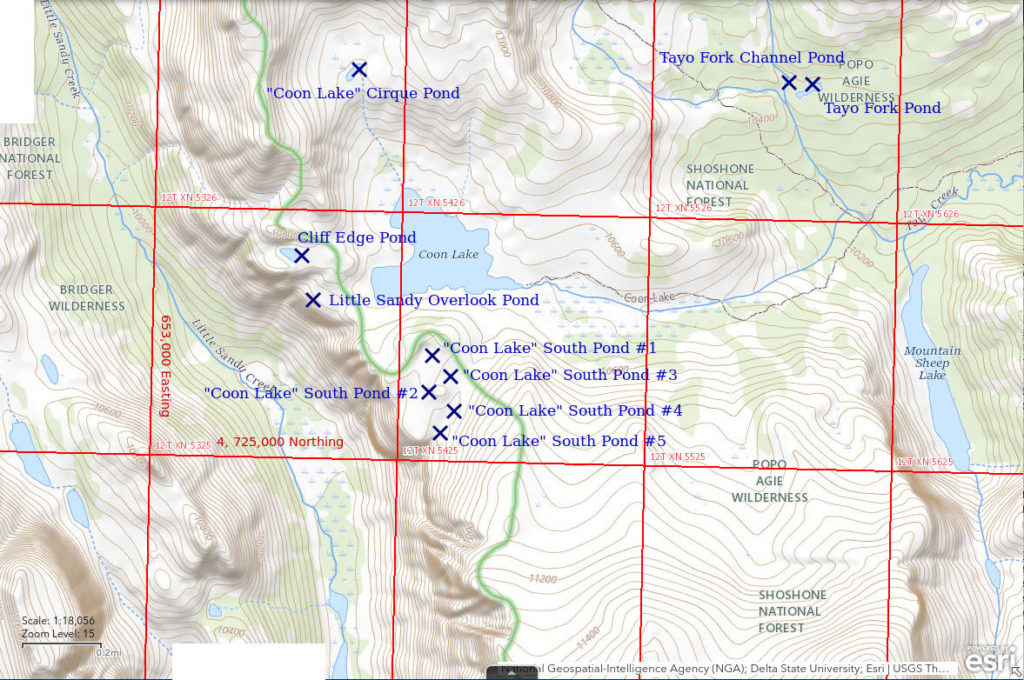

Little Sandy Overlook Pond

“Coon Lake” South Pond #1

“Coon Lake” South Pond #2

“Coon Lake” South Pond #3

Cliff Edge Pond

“Coon Lake” South Pond #4

“Coon Lake” South Pond #5

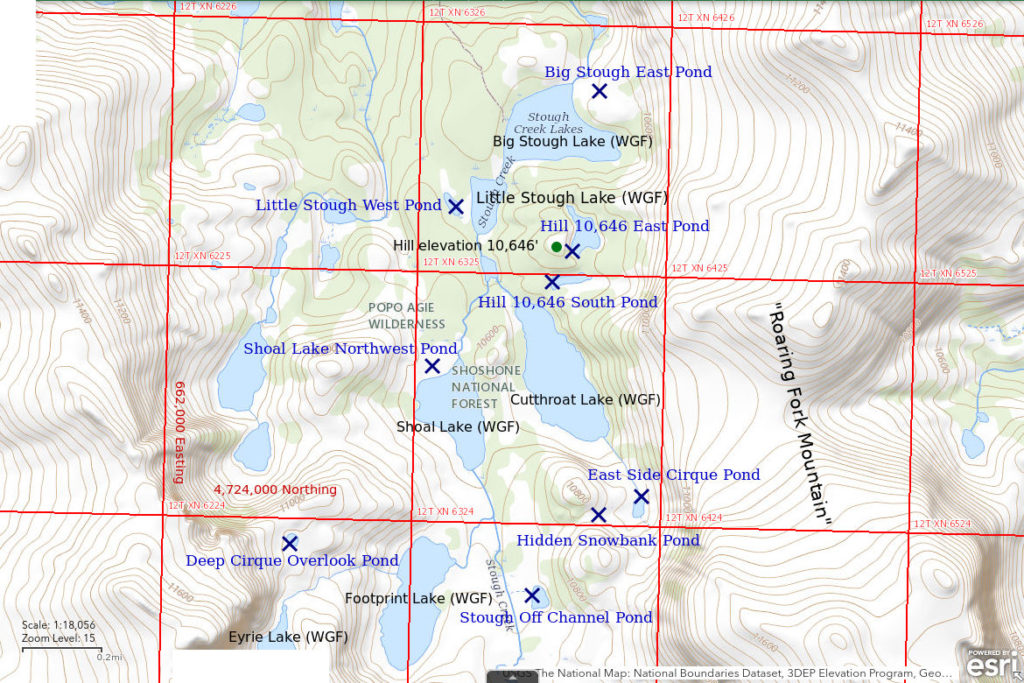

Big Stough East Pond

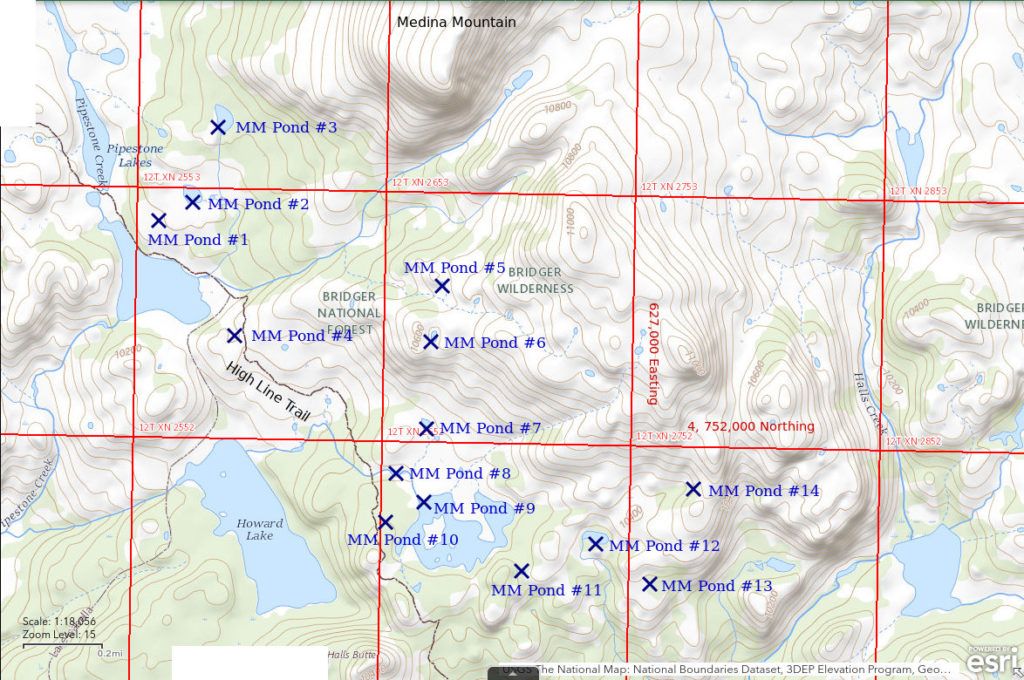

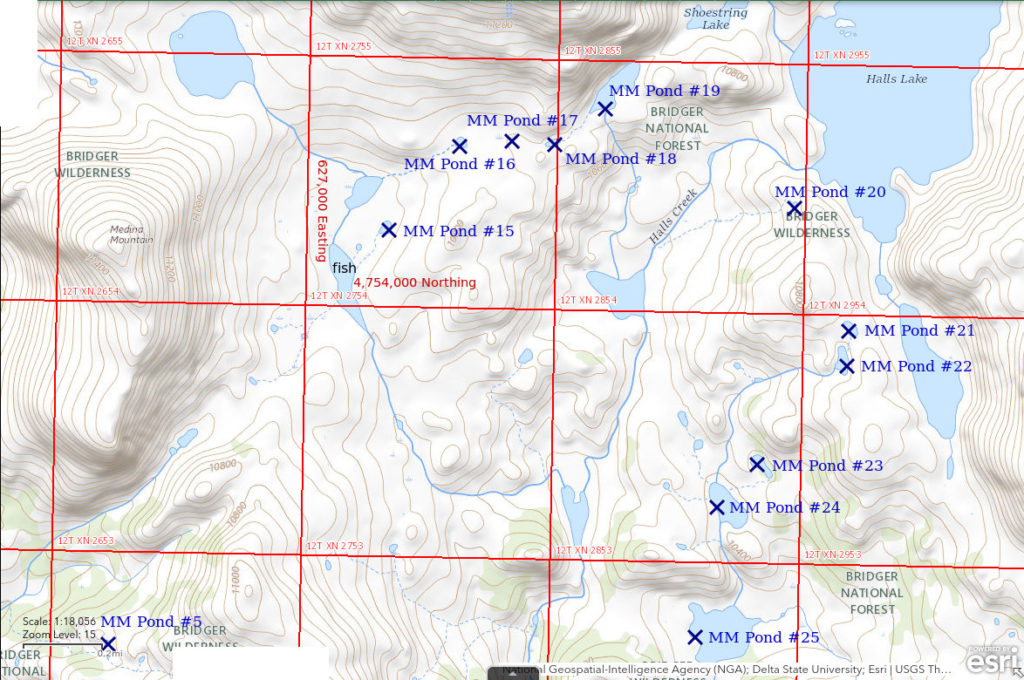

Medina Mountain Ponds

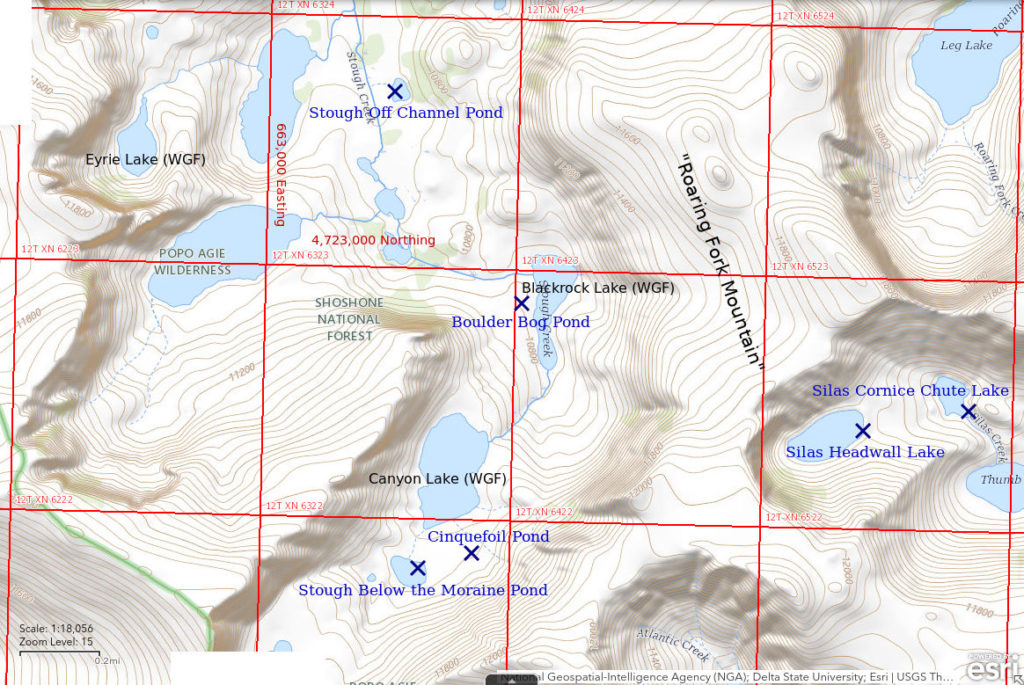

Silas Headwall Lake

Silas Cornice Chute Lake

Cinquefoil Pond

Stough Below the Moraine Pond

Boulder Bog Pond

Deep Cirque Overlook Pond

Shoal Lake Northwest Pond

Hill 10,646 East Pond

Hill 10,646 South Pond

East Side Cirque Pond

Hidden Snowbank Pond

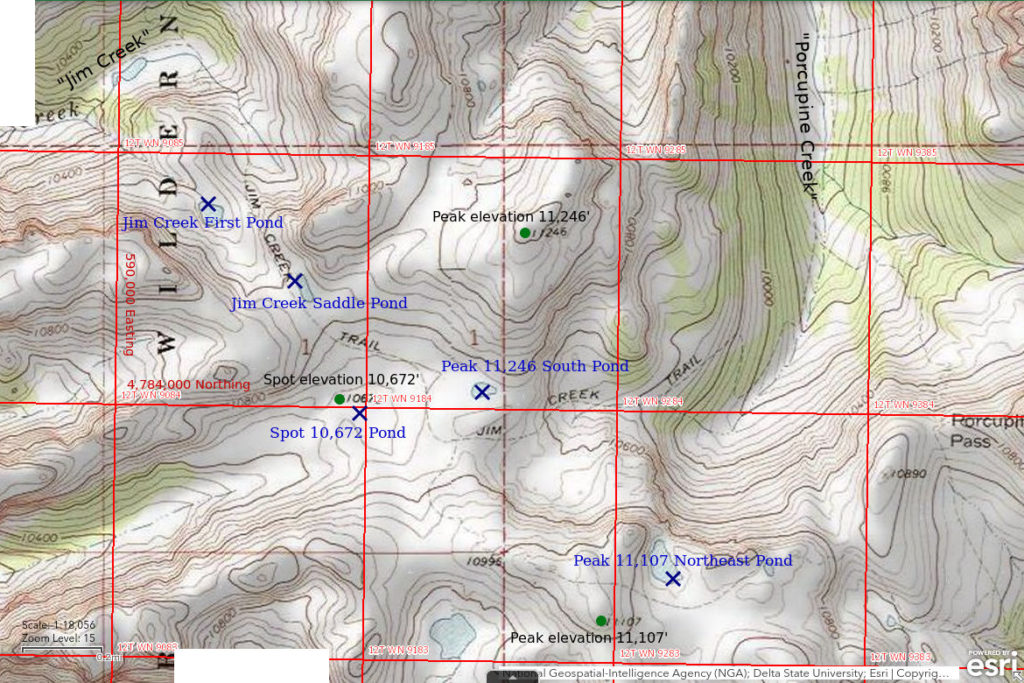

Jim Creek Saddle Pond

Jim Creek First Pond

Spot 10,672 Pond

Peak 11,246 South Pond

Peak 11,107 Northeast Pond

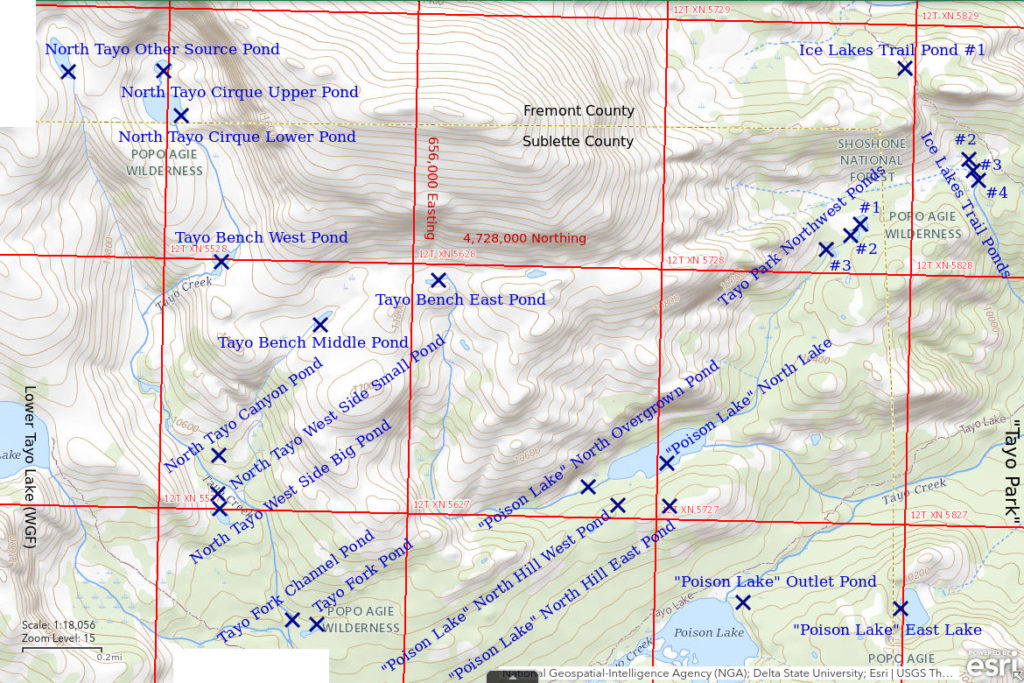

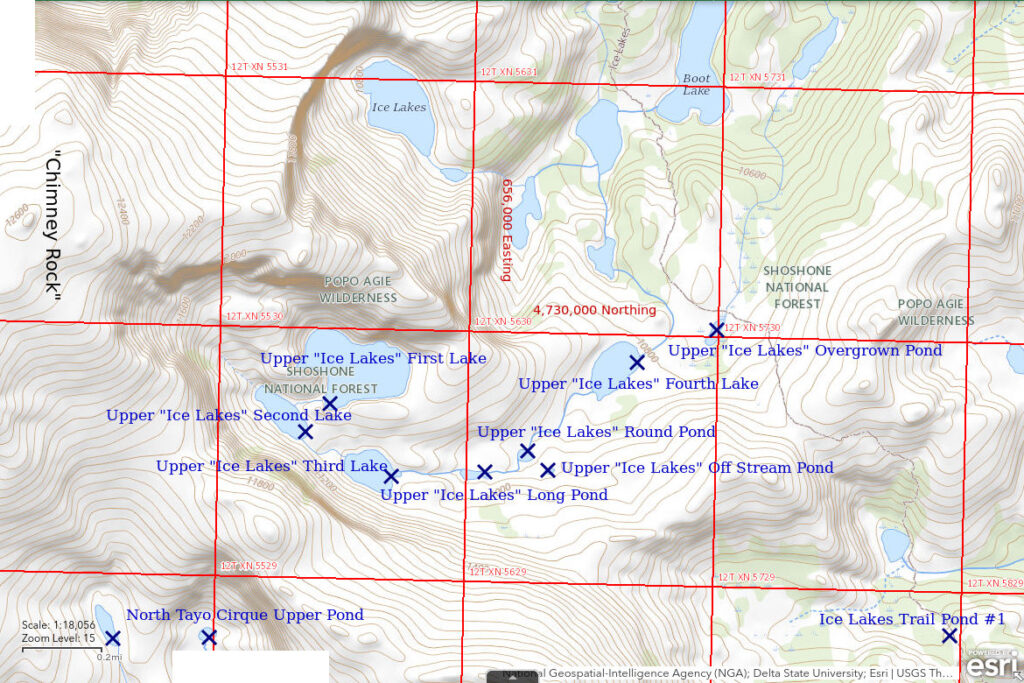

Wind River Peak Ponds

Little Stough West Pond

Stough Off Channel Pond

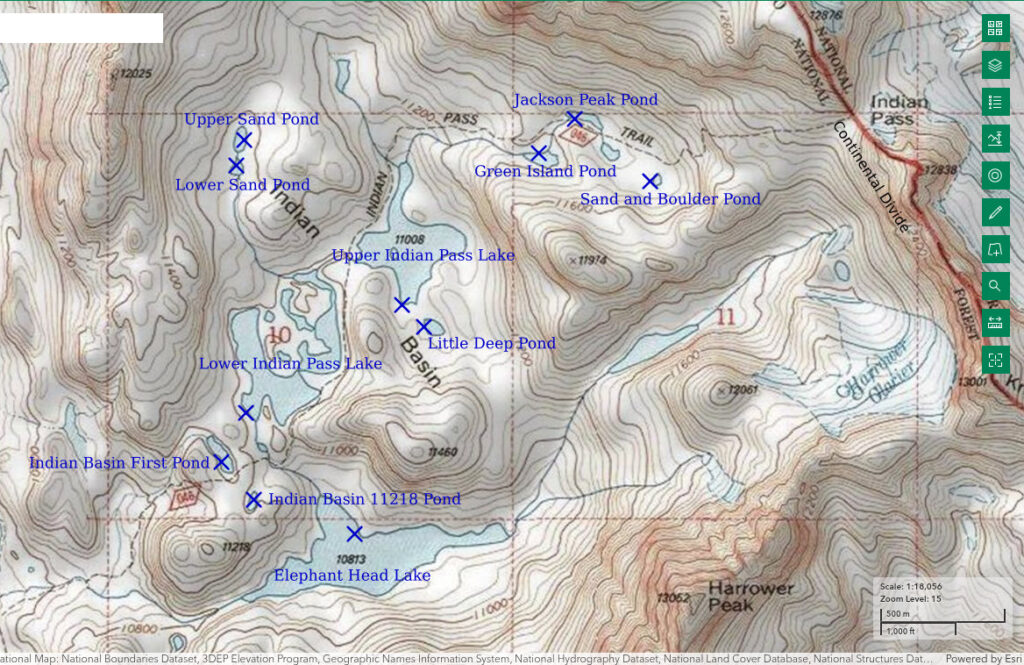

Lower Indian Pass Lake

Jackson Peak Pond

Little Deep Pond

Upper Indian Pass Lake

Upper Sand Pond

Lower Sand Pond

Indian Basin 11218 Pond

Indian Basin First Pond

Elephant Head Lake

Sand and Boulder Pond

Green Island Pond

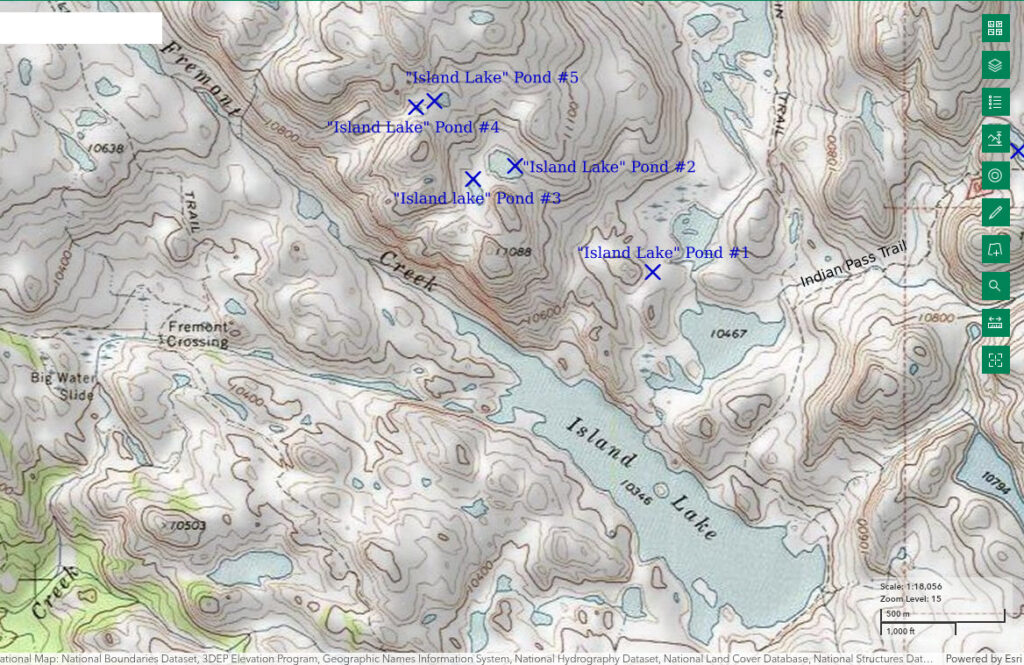

“Island Lake” Pond #1

“Island Lake” Pond #2

“Island Lake” Pond #3

“Island Lake” Pond #4

“Island Lake” Pond #5

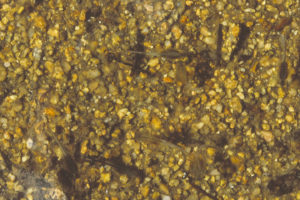

What Can We Learn from the Ponds in the Wind River Mountains?

The Wind River Mountains are the highest and largest mountain range with the most glaciers in Wyoming, although the Laramie Mountains are longer (visual estimates of 1:500,000-scale map of state). They are 170 km (105 miles) long from the US 26 crossing of the continental divide at Togwotee Pass to the Wyoming 28 crossing of the divide at South Pass. The Wind River Mountains are 60 km (37 miles) wide at their mid-section from the lower end of “Fremont Lake” at the edge of the Green River Basin to the upper end of Bull Lake at the edge of the Wind River Basin. At their north end, they give way to the Gros Ventre Mountains to the west and the Absaroka Mountains to the north. At the south end, the Wind River Mountains become more and more subdued until they are lost in the low hills and ridges of the South Pass area and the Antelope Hills.

The elevation range of the Wind River Mountains is about 2,000 m (6,560′). Gannett Peak has an elevation 4,207 m (13,804′) and there are several other peaks above 4,000 m (13,120′), such as Wind River Peak 68 km (42 miles) to the southeast. Elevations along the base of the range are variable. “Fremont Lake” at the base of the mountains on the west side is 2,260 m (7,410′) while “Bull Lake” on the east side is 1,770 m (5,810′). 55 km (34 miles) to the southeast of “Bull Lake”, the mouth of Sinks Canyon is at 2,260 m (7,410′). South of “Fremont Lake” on the west side, “Boulder Lake” is at an elevation of 2,222 m (7,290′) and the mouth of Big Sandy River is at 2,304 m (7,560′). On the northeastern side of the range, the slope up to the divide is more or less continuous. On the southwestern side of the divide, however, there is commonly a sharp rise from the Green River Basin, then a more horizontal but still quite rugged area up to 12 km (7.5 miles) wide (e.g., Pine Mountain to “Lower Jean Lake”) between the elevations of 3,000 m (9,840′) and 3,500 m (11,480′), and finally another rise to the highest peaks and ridges near the Continental Divide.

The average annual precipitation on the Wind River Mountains prior to 1986 was greater than 40 inches (102 cm), as water, according to Pochop and others (1989). Mean Annual Precipitation according to the Wyoming Climate Atlas by the Water Resources Data System and State Climate Office at http://www.wrds.uwyo.edu/sco/climateatlas/precipitation.html, Parameter-Elevation Regressions on Independent Slopes Model, PRISM, with 1971-2000 data at very widely spaced weather stations (I have eyeballed the values from a very small scale map with 11 precipitation bins marked with indistinct colors and further obscured by a shaded relief base map):

31″-40″ (79-102 cm) up to maybe 51″-60″ (130-152 cm) on the crest

Much of the Wind River Mountains is above timberline where the vegetation is dominantly alpine tundra. With decreasing elevation, trees become abundant, starting with white pine krummholz and proceeding downward through full-size white pine, fir, spruce, douglas fir, and lodgepole pine. Lush meadows are common. Sagebrush is abundant in the foothills.

The Wind River Indian Reservation occupies a part of the Wind River Mountains. The reservation is approximately a rectangle with west-east and north-south boundaries. The southwestern corner of this rectangle is truncated at the Continental Divide, where it lies between the Fitzpatrick and Popo Agie wildernesses. The reservation boundary along the divide is 16 km (10 miles) long and the reservation expands northeastward from there to cover approximately 1,994 square kilometers (770 square miles) of the mountain range, including foothills. For comparison, this area is 15% larger than that of the Bridger Wilderness alone, which doesn’t include foothills.

The Wind River Mountains are a paradise of public lands for hikers. The car-tethered masses are drawn to the scenic wonders of Teton and Yellowstone National Parks farther to the northwest. There are no roads through the Wind River Mountains south of Union Pass, near the northern end. The only choices are to walk or ride a horse. The Bridger-Teton National Forest manages the mountains to the southwest of the Continental Divide and the Shoshone National Forest manages the mountains to the northeast. Probably 75% (EIGWUU) of the National Forest lands in the mountains are Wilderness Areas totaling about 2,947 square kilometers (1,138 square miles) (as stated on U.S. Forest Service recreation maps): the Bridger Wilderness on the Bridger-Teton and the Fitzpatrick and Popo Agie wildernesses on the Shoshone. Other than a few parcels of private land along the upper Green River north of Pinedale, there are no private in-holdings. Non-tribal members who want to visit or cross the Wind River Indian Reservation must purchase a trespass permit.

Black bears and grizzly bears roam throughout the Wind River Mountains. Black bears were never extirpated from the Wind River Mountains. Grizzly bears have spread southward from Yellowstone National Park over the last 30 years or so. Neither the U.S. Forest Service nor the Wyoming Game and Fish Department provide information on bear populations, where they are most common, sightings, or attacks. Carrying bear spray is advised. Visit https://www.fs.usda.gov/r04/bridger-teton/safety-ethics/be-bear-wise-keep-bears-wild-people-safe for more about bears. The Bridger-Teton National Forest requires that off-road campers secure all food and any other items that may attract bears in bear-resistant containers or in bags hung at least 10′ (3 m) above the ground. The June 14, 2023 order by the Forest Supervisor is at https://www.fs.usda.gov/r04/bridger-teton/alerts/food-storage-blackrock-jackson-pinedale-greys-river-big-piney-ranger. At the same time, WGF allows hunters to set bear baits. In 2025, black bear seasons in the Bridger Wilderness (Area 19) were May 1 – June 15 and August 1-31. If you notice something that smells like rotten meat or a dead animal, do not linger.

Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Glacial Features

Rock Exposure Ages Determined by Cosmogenic Isotope Dating

Complications of Beryllium-10 Dating

Exposure Ages of Pinedale Moraines

Exposure Age of “Titcomb Lakes” Moraine

Exposure Ages of “Temple Lake” and “Alice Lake” Moraines

Exposure Ages of Glacier Retreat East of the Continental Divide

Exposure Ages of Moraines in Stough Creek Basin

Little Ice Age Glaciation

Summary of Pond History

Glacial Features

Glaciers have played a major role in creating an abundance of potential fairy shrimp habitat in the Wind River Mountains. The landscape is a wonderland of heart-stopping cliffs, compelling cirques, deep u-shaped valleys, polished knobs of bedrock, daunting piles of boulders, and incredible vistas. Static water bodies though are limited to the flatter areas. Cirques, the floors of valleys, benches on the canyon walls left by successive glacial advances, and glacial gouges between the major canyons are all important sites for ponds. The highest density of ponds seems to be in a broad, rugged upland southwest of the high peaks and of the Highline and Fremont trails, generally. Have a look at “Ross Lake” to see what only glaciers can do.

The narrow glacial canyon of “Ross Lake”. The valley glacier that formed “Ross Lake” didn’t head straight down hill toward the Wind River Basin. It started out headed east but then turned sharply to the north to follow a zone of weakness in the bedrock. But gravity wanted it to go down hill more. The ice spilled out of the valley where “Ross Lake” now lies and cut a broad path through the rock where West Torrey Creek now flows. The outlet of the lake is on the far side of the bare rock hill at lower left.

Of course, all these glacial features were previously covered by ice. The ice had to melt before the fairy shrimp could arrive. When the ice melted has important implications for the timing and rate of pond colonization by fairy shrimp. The earlier the ice melted, the more likely a pond has been colonized. However, colonization also depends on the dispersal rate and the dispersal rate depends on the activities of the dispersing animals and the presence of habitats favorable for those animals. Habitats could change with climate fluctuations after the ice melted and predators could eliminate fairy shrimp from previously colonized ponds but those are second-order effects. The ice had to melt first.

Earth has experienced several glaciations in the last million years but only the most recent in the Wind River Mountains is relevant for the current distribution of fairy shrimp there. The last major glacial advance in the Wind River Mountains is marked topographically and geomorphologically by Pinedale moraines. Moraines are piles of angular boulders, cobbles, gravel, sand, and finer material that were pushed down or across slopes by the leading and lateral edges of glaciers. They are called Pinedale because a prominent such moraine formed around “Fremont Lake”, near Pinedale. Moraines are usually ridges with arcuate or linear forms mimicking the former ice margins and have heights up to a few tens of meters (up to a few 100 feet) (Schaller and others, 2009). Pinedale moraines have been identified in several valleys of the Wind River Mountains. The term Pinedale has also been applied to glacial features elsewhere in the western United States that are approximately the same age as the Pinedale moraines in the Wind River Mountains (e.g., Young and others, 2011a).

The loose rock in this photograph is part of a moraine above Upper “Par Value Lake” in the East-Central Sierra Nevada. Here, the moraine does not form a narrow ridge but is more a broad mass with local ridges (at left) and troughs (center, with “Par Value” 2nd West Pond).

Here’s an arcuate moraine below Wind River Peak that has only recently been revealed by the retreating ice. The lowest part of the glacier is covered by rock debris that may be from rock falls and slides or that was previously buried in the ice.

Moraines can be used as time markers. Glaciers moving down valley destroy any existing moraines they cross. Consequently, the moraine that is the farthest down the valley is the oldest and any other moraines get younger up the valley. These recessional moraines represent minor pulses of glaciation during the overall retreat or a more limited advance after a retreat. The lateral moraines on valley walls are older at the top. Once the ice starts melting, lateral moraines formed by minor subsequent glacial pulses are lower on the valley walls because the glacier is thinner. Typically, the youngest moraines are near the bowl-like cirques at the upper ends of glacial valleys. Or they may form below shadowed cliffs without a bowl. In addition to relative position, the angularity of the rocks on a moraine, the steepness of the piles, and the depths of soil can be used to determine relative moraine ages. Older moraines have more rounded boulders and deeper soils due to weathering and their slopes are shallower due to erosion (Schaller and others, 2009).

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Rock Exposure Ages Determined by Cosmogenic Isotope Dating

While relative ages of moraines are helpful, absolute ages are necessary to determine fairy shrimp colonization rates. And now we have them thanks to super-precise instruments and analytical techniques developed by the mid-1980s (Bierman and others, 2002). Earth’s surface receives a continuous shower of cosmic rays. When cosmic rays collide with atoms, the ensuing reactions result in the formation of various nuclides. “Nuclide” seems to be jargon for an atom that started off as a fragment of a nucleus. The nuclide most commonly used for dating geological surfaces is beryllium-10. The most common isotope of beryllium is beryllium-9. Beryllium-10 has 4 protons and 6 neutrons and is produced in greatest abundance by the splitting of silicon-28 (14 protons and 14 neutrons) and of oxygen-16 (8 protons, 8 neutrons) by those cosmic rays that are fast neutrons. Cosmic ray muons can also cause reactions that produce beryllium-10. However, muon production rates are so low that they can usually be ignored (Balco and others, 2008). Nonetheless, some labs include muon production rates in their calculations (e.g., Bierman and others, 2002). Using equations for how much beryllium-10 is produced by cosmic rays over time and for how much beryllium-10 is lost due to radioactive decay over time, how long a rock has been exposed at the surface can be calculated. These exposure ages indicate when the glacier above the rock melted away.

Quartz is the most commonly analyzed mineral for cosmogenic nuclide dating (Bierman and others, 2002). It has relatively high beryllium-10 production rates because it is composed of silicon and oxygen but it also has a few impurities. Quartz is a common mineral that occurs in many rocks, most notably granite and sandstone. Serendipitously, granite and similar rocks are commonly exposed in the glaciated mountain ranges of the western United States.

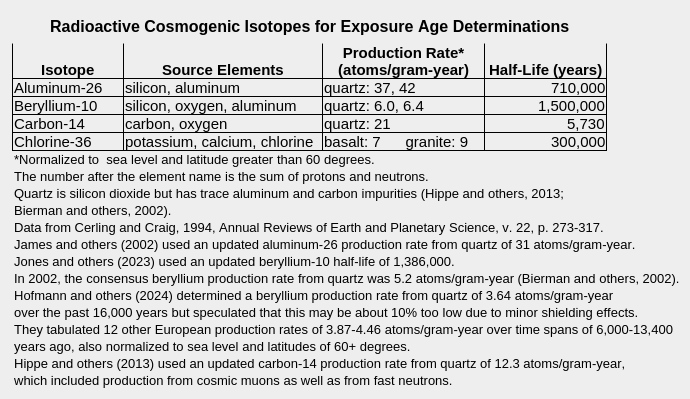

Radioactive cosmogenic isotopes of aluminum, chlorine, and carbon have also been used for exposure dating, as summarized in the table of Radioactive Cosmogenic Isotopes for Exposure Age Determinations. Stable cosmogenic isotopes such as helium-3, xenon-131, and neon-21 have been used to determine ages of young volcanic flows with low potassium concentrations that make them unsuitable for potassium-argon dating. They have also been used to determine exposure ages of 3 billion year old shale in Swaziland, of alluvial diamonds in Zaire, and of desert pavement in the western U.S. (Cerling and Craig, 1994).

For exposure age studies, chlorine-36 concentration has generally been measured in rocks rather than in individual minerals. Unlike minerals, rocks don’t have fixed concentrations of potassium, calcium, and chlorine, the sources of cosmogenic chlorine-36. Consequently, the concentrations of potassium, calcium, and nonradioactive chlorine in the rock must be measured before an exposure age can be calculated. By analyzing calcium-rich plagioclase and potassium-rich sanidine in independently dated volcanic flows, Schimmelpfennig and others (2011), determined chlorine-36 production rates of 42 atoms/gram-year for calcium and 125 atoms/gram-year for potassium. The source cited by Cerling and Craig (1994) for the chlorine-36 production rates from basalt and granite in the table above estimated calcium production rates of 76 atoms/gram-year and potassium production rates of 106 atoms/gram-year (Schimmelpfennig and others, 2011, Table 1). These production rates, combined with the much smaller production rate of chlorine-36 from chlorine-35 by capture of thermal neutrons, can be multiplied by the concentrations of calcium and potassium in a rock sample to derive the chlorine-36 production rate for the rock.

The flux of cosmic rays is attenuated as it passes through atmosphere, ice, and rock somewhat in proportion to the density of the medium transited. Atmospheric attenuation is weak and a large proportion of cosmic rays make it through. Ice 5.5 m (18′) thick blocks most cosmic rays and renders the beryllium-10 production rate negligible (Fabel and Harbor, 1999). A rock thickness of 45 cm absorbs about half of the fast neutrons (Bierman and others, 2002). Below a depth of 175 cm (69″) in rock, the production rate of beryllium-10 is only 5% of the rate at the surface (Fabel and Harbor, 1999).

Rocks that have never been at the surface have negligible beryllium-10. Rocks that have been buried for a long time also have negligible beryllium-10. After about 7 million years, the concentration of beryllium-10 is reduced to about 3% of its starting value due to radioactive decay. Glaciers rip up and scour the rocks beneath them. If a glacier removes 2 m (6.6′) or more of rock, the rock remaining at the surface below the glacier will have negligible beryllium-10. If the glacier is thick enough to block cosmic rays, the rock underneath it will continue to lack beryllium-10. Once the ice melts, though, the surface rock will begin to accumulate beryllium-10 due to cosmic ray impacts on silicon and oxygen atoms. The math is complicated but the date when the ice melted can be calculated using the cosmogenic production rate and the half-life of radioactive decay (Cerling and Craig, 1994). Due to the slow cosmogenic production rate, it takes more than decades to accumulate a measurable amount of beryllium-10. For what it’s worth, Jones and others (2025) reported a beryllium-10 date of 0 years with an uncertainty of 30 years. Beryllium-10 dating works better for time spans of a thousand to a few hundred thousand years (Bierman and others, 2002). Dating exposure more than a few million years ago is dubious. Over such long time spans, rocks are likely to have complex and unknowable histories of burial, which blocks cosmic rays, and erosion, which removes rock that has been exposed to cosmic rays (Fabel and Harbor, 1999).

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Complications of Beryllium-10 Dating

Beryllium-10 dating is complicated by several processes. First, one needs an estimate of the local production rate of beryllium-10. This usually requires comparing beryllium-10 dates to dates obtained by other methods. This has been done at only a few sites globally (Hofmann and others, 2024). Assuming that a study area has the same production rate, after appropriate scaling, as that measured at a site far away adds uncertainty to the results of dating. For example, Hoffman and others (2024) determined a production rate in the Black Forest of Germany that was 89% of the nearest previously determined production rate in Switzerland. They attributed the difference to thin soil, moss, and shrubs blocking more cosmic rays from the boulders at the German site than at the Swiss site.

Another factor that has to be taken into account is geometric shielding of cosmic rays (Fabel and Harbor, 1999). The same areas on horizontal or inclined rock surfaces will not be impacted by the same flux of cosmic rays. Most researchers sample the most horizontal surfaces they can find (e.g., Dahms and others, 2018). The blocking of low-angle cosmic rays by mountains, trees, and other elevated objects has to be considered. Hippe and others (2013) estimated topographic shielding factors of 0.821-0.993 for 12 samples in the Gotthard Pass area of Switzerland. A factor of 1.0 would indicate no shielding.

To allow comparisons of exposure ages at different locations, scaling by elevation accounts for variable cosmic-ray attenuation in the atmosphere and scaling by latitude accounts for variations in cosmic ray flux due to Earth’s dipole geomagnetic field (Bierman and others, 2002). The orientation and strength of the dipole field varies with latitude. Latitude scaling alone though ignores changes in the orientation and strength of the geomagnetic field over time (e.g., polar wander, dipole weakening, and reversal). Desilets and Zreda (2006) proposed corrections for temporal changes in the geomagnetic field. Hippe and others (2013) did not consider changes in geomagnetic field intensity over time but Hofmann and others (2024) did. Cosmic ray fluxes also vary with solar flares, the decadal solar cycle, and other heliospheric and galactic properties over centuries and millennia (Desilets and Zreda, 2003). If such variations cancel out over thousands of years, they can be ignored in studies of Earth’s most recent major glaciation.

In addition to the physical processes that affect the accumulation of beryllium-10 in a rock, there are geological processes to consider. A sample used to determine the time when ice melted off a rock must not have been buried or eroded since the ice melted. Burial reduces the beryllium-10 exposure age by blocking cosmic rays. Erosion, even of a few centimeters, also reduces the exposure age by removing the parts of the rock that were impacted by the most cosmic rays (Fabel and Harbor, 1999). In sampling moraines for dating, glaciologists choose the biggest boulders that rise the farthest above the adjacent moraine in order to avoid the effects of burial (e.g., “only tall boulders should be sampled”, James and others, 2002). Boulders higher than slope wash would also avoid erosion. In contrast, low boulders on the slopes of moraines could have been buried and then more recently exposed by erosion of overlying moraine material. In sampling bedrock, outcrops that rise well above surrounding rock debris and soil are less likely to have been buried than low lying outcrops. Glaciers themselves provide key clues for avoiding eroded bedrock. In scraping the underlying rock, they leave smoothly polished surfaces, striations gouged by rocks embedded in the lowest layer of ice, and chatter marks or crescentic fractures caused by plucking chunks off the underlying rock (e.g., Figure 2 in Hippe and others, 2013). If these features are present, erosion since the ice melted off must have been minimal. Quartz veins are good sample sites as quartz is one of the hardest and least easily eroded minerals.

In spite of the care taken to minimize the possibilities of burial and erosion effects, many studies of glacial exposure ages have reported young outliers that could be due to burial or erosion. For example:

- Of 10 samples from a transect of striated bedrock above Fordyce Creek on the west side of the Sierra Nevada, the uppermost yielded an anomalously young age of 8,400 years (standard deviation 1,600 years, James and others, 2002). The next lower sample, which would have been exposed more recently as the glacier melted, had an age of 16,800 years (standard deviation 1,600 years) and a sample from the bottom of the valley had an age of 14,700 years. The outlier was “interpreted as the result of postglacial burial or nivation”.

- Phillips and others (2009) reported 2 anomalously young samples in their study of moraines on the east side of the Sierra Nevada: 6,600 years (BPCR91-2) vs. a mean of 17,600 years (standard deviation 800 years) for the other 6 samples from one site and 10,400 years (BPCR90-23) vs. a mean of 17,900 years (standard deviation 700 years) for the other 4 samples from another site.

- Young and others (2011a) excluded a young outlier age of 13,500 years from a Pine Creek valley, Colorado, cluster averaging 15,800 years (standard deviation 400 years, n=6) due to suspected burial.

- Rood and others (2011) found no young age outliers for the northern lobe of a Tioga moraine at Sonora Junction on the east side of the Sierra Nevada but 1 each for the Tioga southern lobe and for a Tenaya moraine: 16,300 years vs. a mean of 19,200 years (standard deviation 600 years, n=6) and 3,300 years vs. 8 other samples ranging from 16,700 to 24,000, respectively. 10 boulders from a Tahoe moraine had exposure ages ranging from 57,000 years to 115,000 years after excluding 2 old outliers. Rood and others (2011) assumed most of the scatter was due to burial or erosion and chose the 3rd oldest age of 115,700 years as the most reliable. Rood and others (2011) further presented all their exposure ages calculated with possible erosion rates of 0, 0.6, and 3.1 meters/million years. They considered the 0.6 rate the most plausible “average” erosion rate for all samples. That rate would result in 1-1.5 cm (0.4-0.6″) of erosion over the 18,000-25,000 year range of the exposure ages. Table 1 of Rood and others (2011) presents previously published ages for 8 other Sierra Nevada glacial features and some appear to have young outliers or mixed populations.

- One of the erratic boulders in the lower Kogalu River valley on Baffin Island had an anomalously young age of 10,500 years (standard deviation 600 years) whereas 12 other ages scatter from 11,900 to 23,900 years (Briner and others, 2005). A cobble south of the outer Eglinton Fiord with an age of 29,500 years (standard deviation 800 years) was also considered a young outlier compared to other samples from the same area (Briner and others, 2005).

- Among 18 data sets with more than 5 samples each from the western United States shown in Figure 1 of Marcott and others (2019), 6 have 1 or 2 young outliers.

- In a review of 24 glaciation dating studies involving 638 boulders, Putkonen and others (2003) found that the difference between the youngest and oldest boulders at a single site averaged 38% of the maximum age, after removal of author-identified outliers. This is more than 3 times the average estimated uncertainties of 12%. How many sites were likely to have young outlier ages could not be determined as I was unable to find the “Appendix” online.

Burial and erosion effects can be detected by discrepancies between exposure ages determined using 2 different radioactive cosmogenic isotopes. The concentration of the isotope with the shortest half-life declines faster after burial or during erosive stripping and this results in a younger exposure age than that of the longer-lived isotope. Interpretation is non-unique but curve-plotting techniques illustrate the possibilities and, combined with geologic knowledge of the site, provide plausible explanations (Fabel and Harbor, 1999). Trial-and-error and Monte Carlo simulations can also yield useful results (e.g., Hippe and others, 2013, and Jones and others, 2023, respectively).

Hippe and others (2013) determined exposure ages of bedrock rather than of moraine boulders using beryllium-10 and carbon-14. They considered erosion unlikely due to well preserved glacial features on rock surfaces but found that 6 of 9 samples had carbon-14 ages 6-20% lower than beryllium-10 ages, which could be due to burial. By assuming 100 cm of snow cover for 6 months every year for the past 11,700-15,900 years, discrepancies between the beryllium-10 and carbon-14 ages were reduced to 2-12% and 2 of the carbon-14 ages were then greater than the beryllium-10 ages.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Jones and others (2023) used Monte Carlo simulations to unravel the exposure histories of bedrock adjacent to the Kokanee Glacier in the Selkirk Mountains, British Columbia, and to Mammoth Glacier in the Wind River Mountains, Wyoming. Bedrock samples were collected less than 200 m from 2018 or 2020 ice margins, respectively, and up slope of the most recent moraine. Multiple simulations of the beryllium-10 and carbon-14 ages indicated the most likely scenario for the Kokanee Glacier was exposure from 11,000 to 7,000 years and then burial by the glacier from about 6,000 years ago to less than 100 years ago. In contrast, Mammoth Glacier did not cover the adjacent bedrock until about 1,000 years ago when it advanced during the Little Ice Age.

The studies of Hippe and others (2013) and Jones and others (2023) illustrate the possibilities for interpreting somewhat complex exposure histories involving burial by comparing the ages of 2 different radioactive cosmogenic isotopes. The simulations of Jones and others (2023) also included the effects of subglacial erosion.

A more inscrutable geologic problem is inheritance. If a rock was exposed before it was covered by a glacier, it would have accumulated beryllium-10. For glaciations younger than a few hundred thousand years, most of that inherited beryllium-10 would still be present when the rock was sampled. More beryllium-10 means an older calculated age and that misleading age could be tens of years or several times as old as the actual exposure age depending on how long the rock was exposed before the glacier buried it and how much of the upper surface of the rock the glacier has scraped off. In fact, several studies have reported anomalously old ages that were explicitly or implicitly interpreted to be due to inheritance. For example:

- A sample from an outcrop that was glacially rounded by the Tioga 3 glacier on the east side of the Sierra Nevada gave an anomalously old age of 21,200 years (BPCR91-11) whereas nearby samples from a Tioga 3 moraine had a mean exposure age of 15,200 years (standard deviation 1,000 years, n=5) (Phillips and others (2009). This was interpreted to mean that the Tioga 3 glacier did not remove all of the outcrop that had been exposed before the Tioga 3 advance.

- Rood and others (2011) considered ages of 21,200 and 22,000 years to be outliers compared to a mean age of 19,200 years (standard deviation 600 years, n=6) for a Tioga moraine at Sonora Junction, in the Sierra Nevada. For the widely scattered ages of 10 boulders of a Tahoe moraine, they excluded old outliers of 148,200 and 159,500 years as the next youngest age was 115,700 years (standard deviation 3,600 years). Table 1 of Rood and others (2011) presented previously published ages for 8 other Sierra Nevada glacial features and some appear to have old outliers or mixed populations.

- Briner and Gifford (2005) found a few old outliers in the exposure ages of various glacial features on the west side of Baffin Island, Canada. Samples from the Patricia Bay moraine gave an average exposure age of 12,500 years (standard deviation 700 years, n=3) and an outlier age of 18,000 years. An outlier of 26,200 years occurred among erratic boulders of the Upper Kogalu River valley, which had a mean exposure age of 13,000 years (standard deviation 1,000 years, n=5). In the Lower Gallup River valley, erratic boulders had exposure ages which clustered at 15,000 years and 24,000 years (sample uncertainties 2,100 years or less, n=13) but there were 2 outliers with ages of 50,500 years and 73,900 years.

- Among 18 data sets with more than 5 samples from the western United States shown in Figure 1 of Marcott and others (2019), 4 have 1 or 2 old outliers.

- In a review of 24 glaciation dating studies, Putkonen and others (2003) found that the respective authors identified 2% of the exposure ages of 638 boulders as too old due to inheritance.

Matthews and others (2017) found no evidence of inheritance in cobbles below a couple of glaciers in Norway. A moraine cobble (maximum length 20 cm, 7.9″) collected 100 m (330′) from the front of a small glacier had a beryllium-10 age of 99 years with an uncertainty of 98 years (2 standard deviations of beryllium-10 analytical error and production rate). A sample of 75 pebbles (sizes 2-13 cm, 0.8-5.1″) collected from a moraine that became ice-free approximately 50 years ago adjacent to another glacier was found to have minimal inheritance (Matthews and others, 2017). The beryllium-10 age of the combined pebbles was 368 years with 90 years as 2 standard deviations of the beryllium-10 analytical error and production rate. Bedrock at both sites was exposed for up to 4,000 years since about 10,000 years ago when the glaciers in southern Norway had disappeared (Matthews and others, 2017). From this, the authors gallantly concluded that warm-based glaciers “are likely to have had their pre-deglaciation cosmogenic signals zeroed” by erosion (Matthews and others, 2017).

However, the study of Jones and others (2023) (see above) can be recast as a study of inheritance. Bedrock samples adjacent to Kokanee and Mammoth glaciers should have had beryllium-10 exposure ages of less than 100 years based on historical evidence of recent glacier shrinkage. In fact, beryllium-10 ages at Mammoth were 5,309-9,307 years (excluding a young outlier) and those at Kokanee were 2,572-5,562 years. Cosmogenic carbon-14 ages were significantly younger but still too old. 6,000 years of glacial action at Kokanee and 1,000 years at Mammoth didn’t come close to zeroing out inherited beryllium-10. Moreover, Jones and others (2023) calculated bedrock abrasion (i.e., without plucking) rates of 20 cm (7.9″) per thousand years at the moderately sloping Mammoth Glacier and 4 cm (1.6″) per thousand years at the steeper Kokanee. At those rates, it would take a glacier 10,000-50,000 years to abrade the 2 m (6.6′) of rock that could contain inherited beryllium-10 if it had been previously exposed (see above).

My sampling of less than about 15 articles is but a small, non-representative sample of the glacier dating literature. No doubt, there are many studies other than those mentioned here that found no evidence of burial, erosion, or inheritance in the sampled rocks.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Exposure Ages of Pinedale Moraines

A good starting point for beryllium-10 exposure ages of moraines in the Wind River Mountains is Young and others (2011b). Those authors compiled close to 100 ages for moraines in Colorado, the Wallowa Mountains in Oregon, the Uinta Mountains in Utah, Teton and Yellowstone National Parks, and the Wind River Mountains. To achieve comparability, all ages were recalculated with the same production rates and scaling factors. This is important to the deglaciation timing arguments of Young and others (2011a). It also “corrects” previously published ages for terminal Pinedale moraines as production rates and scaling factors have been progressively refined. Individual boulders from terminal Pinedale moraines yielded exposure ages of 22,700, 24,300, and 24,700 years ago at “Fremont Lake”; 20,500 and 24,700 years at nearby “Soda Lake”; and 21,800 and 22,100 years at nearby “Half Moon Lake” (Young and others, 2011b, Table DR-1). For analytical uncertainty, standard deviations of 700 years were reported. All 3 “Fremont Lake” dates are within analytical error of the 24,300 years median and have a mean of 23,900 years. The “Soda Lake” and “Half Moon Lake” age pairs each have an age that is well below the “Fremont Lake” median and could be due to erosion or burial. Including the other 2 ages in the “Fremont Lake” mean doesn’t change much and seems arbitrary.

Boulders on a terminal Pinedale moraine at “Bull Lake” on the Wind River Indian Reservation east of the Wind River Mountains had beryllium-10 ages of 16,000-23,000 years ago (Phillips and others, 1997, abstract only). These ages were said to be “nearly identical” to ages for the Pinedale moraine at “Fremont Lake”. Presumably, the maximum age of 23,000 years would still be consistent with the “Fremont Lake” mean after correction. Ages much younger than 23,000 years must apply to recessional (see below) rather than terminal moraines.

On the southeastern flank of the Wind River Mountains south of the Wind River Indian Reservation, a terminal Pinedale moraine has been dated at the mouth of North Popo Agie River canyon. Boulders on the moraine at Pine Bar Ranch gave ages of 22,500 and 23,300 years ago with standard deviations of 2,300 years (Dahms and others, 2018). Both are within analytical uncertainty of the “Fremont Lake” mean but a mean of 22,900 years is more appropriate for this site.

Dating of recessional moraines up valley from the terminal Pinedale moraines at “Fremont Lake” documents a period of retreat lasting 4,000 years. Recessional moraine boulders near “Fremont Lake” had beryllium-10 ages of 16,300, 17,600, 17,700, 17,800, 18,100, 18,200, 18,600, 18,700, 19,100, and 19,100, years ago (Young and others, 2011b, Table DR-1). The locations of the moraines and how far they are from the terminal moraine are not known as only the abstract of the source of the dates is available (Gosse and others, 1995, abstract only). During this time, the glacier that formed the terminal moraine could have retreated the 14 km (8.4 miles) to the north end of “Fremont Lake” and then some distance up the deep valleys of Pine Creek and Fremont Creek. Other valley glaciers draining the rugged upland southwest of the high peaks could have retreated up the deep, u-shaped valleys of “Willow Lake” and Bluff Park Creek, “New Fork Lake” and New Fork River, Porcupine Creek, and Green River above “Lower Green River Lake”. Concurrently, ice and snow would have melted off the uplands to some extent, perhaps revealing “Bridger Lakes”, “No Name Lakes”, “Thomson Lakes”, and others by about 16,000 years ago. Slopes of the higher hills probably rose above the remaining ice.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Exposure Age of “Titcomb Lakes” Moraine

The next time marker up hill from Pinedale recessional moraines is the inner “Titcomb Lakes” moraine between upper and lower “Titcomb Lakes”. Gosse and others (1995, abstract only) published beryllium-10 ages of 11,400-13,800 years ago. The recalculated individual boulder ages are 12,000, 12,000, 12,600, 12,700, 12,800, 12,900, 13,200, 13,200, and 13,500 (standard deviations of 400 years for all) (Young and others, 2011b, Table DR-1). The mean is 12,800 years. The difference between the oldest and youngest of 1,500 years exceeds analytical uncertainty and suggests the mean would be more precise (and maybe more accurate) if the 2 youngest ages were omitted. Doing so would give a mean of 13,000 years. Dahms and others (2018) reported a recalculated mean of 13,300 years. This could be 13,500 years if Dahms and others (2018) included the 2 youngest ages.

Titcomb Basin is the first flat spot west of the Continental Divide between Mt. Wilson and Fremont Peak and the moraine is about 3 km (1.8 miles) below the 1966 terminus of Twins Glacier. The location of a moraine this high in the mountains indicates that almost all of the Wind River Mountains had become ice-free by about 13,300 years ago. The glaciers remaining at that time were tucked up close to both sides of the Continental Divide but were more extensive than their mid-20th century areas.

Upper Indian Pass Lake has fairy shrimp and is in a different drainage only 2,200 m (7,220′) southeast of lower “Titcomb Lake”. It has an elevation of 3,355 m (11,010′) compared to 3,223 m (10,575′) for lower “Titcomb Lake”. Although a little higher than the dated moraine, it was probably also uncovered by 13,300 years ago because there is no glacier, or even a cirque, above it. There are just the exposed southern and western flanks of Fremont Peak and Jackson Peak, which are not conducive to permanent ice. Indian Basin is entirely free of fish. I found fairy shrimp in 4 of 11 ponds in Indian Basin. 3 are appreciably higher than Upper Indian Pass Lake. Assuming they were all ice-free by 12,000 years ago (i.e., melt-off of Cirque of the Towers, see below), the implied colonization rate is 3.0% of available ponds per 1,000 years, averaged over the whole period. That seems pretty slow but I haven’t read of any other colonization rates that I can compare it to.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Exposure Ages of “Temple Lake” and “Alice Lake” Moraines

Glaciers melted off the southwestern Wind River Mountains a little earlier. Dahms and others (2018) reported beryllium-10 ages for boulders on “Temple Lake” moraines from Marcott (Ph.D. dissertation, 2011) of 12,400, 14,300, 14,800, 15,500, 15,700, 15,800, and 16,500 years with standard deviations of 1,200-1,600 years. Excluding 12,400 years, a mean age of 15,300 years was favored by Dahms and others (2018). The difference between the 13,300 age of the “Titcomb Lakes” moraine and the 15,300 age of the “Temple Lake” moraine could reflect real geographic variability. “Temple Lake” and lower “Titcomb Lake” are approximately the same elevation (3,246 m vs. 3,223 m) and the “Temple Lake” moraine is barely 1,500 m (4,920′) below the 1968 Temple Peak glacier (based on 1968 aerial photographs for the 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle). Earlier glacial retreat at “Temple Lake” is nevertheless plausible because its ice-shed is much smaller than that of “Titcomb Lakes”.

“Coon Lake”, south of Wind River Peak, is more exposed to sunshine and at about the same elevation as “Temple Lake”, 3,210 m (10,530′). It, and the fairy shrimp ponds to the south (e.g., Little Sandy Overlook Pond map) could have melted off by 15,300 years ago too.

There is one more time marker southwest of the Continental Divide, a moraine above the “Temple Lake” moraine. This moraine impounds “Alice Lake”, which is in contact with the Temple Peak glacier on the 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle (1968 aerial photographs and “limited revisions” based on 1989 photos). “Alice Lake” is labeled in Figure 1 of Zielinski and Davis (1987). I haven’t found ages for this moraine but Dahms and others (2018) correlated exposure ages of 13,200-13,900 years for moraines in Stough Creek Basin to those of the “Alice Lake” moraine. In a confusing twist, Dahms and others (2018) also considered ages of 9,900-13,600 as correlative with the exposure age of the “Alice Lake” moraine. In any case, given the high elevation of “Alice Lake”, most of the ponds west of the Divide from “Little Sandy Lake” to “North Fork Lake” that were not in close proximity to the Divide were likely free of ice by 13,550 years ago (middle of 13,200 and 13,900 range). This exposure age conveniently matches the 13,300 years age for exposure of “Titcomb Lakes” and, by implication, most other ponds in the northern Wind River Mountains not adjacent to current glaciers. Accordingly, Dahms and others (2018) correlated the “Titcomb Lakes” moraine age with the “Alice Lake” moraine age (although they used the term alloformation).

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Exposure Ages of Glacier Retreat East of the Continental Divide

Boulders in Sinks Canyon in the southeastern Wind River Mountains near Lander were interpreted as belonging to distinct Pinedale recessional moraines. The 2 boulders farthest downstream gave beryllium-10 ages of 19,700 and 21,400 years ago and were estimated to be 1.1 km (0.7 mile) upstream of an ill defined terminal moraine (Dahms and others, 2018). 2 boulders 1.5 km (0.9 mile) farther upstream gave ages of 18,700 and 20,100. Standard deviations were 1,800-2,100 years. Because the terminal moraine at Pine Bar Ranch was approximately 22,900 years old, the boulder with the 18,700 age indicates glacier retreat was well underway within 4,000 years of the terminal moraine melting off. At “Fremont Lake”, the oldest recessional boulder age of 19,100 years ago pegs significant glacial retreat within 5,000 years of terminal moraine exposure but the relevant distances are not available.

The retreat of the glacier up Sinks Canyon and the Middle Popo Agie River valley is further constrained by beryllium-10 ages on glacially polished and striated bedrock surfaces on the canyon walls. A sample 6 km (3.6 miles) up valley from the inferred position of the terminal Pinedale moraine in Sinks Canyon and about 100 m (330′) above the valley floor had a beryllium-10 exposure age of 15,400 years (standard deviation 1,700 years) (Dahms and others, 2018). The glacier had melted off Buttress Pond by then as the pond is down the valley from the sample and well up on the canyon wall. Fairy shrimp could not have arrived at “Poison Lake” Outlet Pond by 15,400 years ago as the pond is something like 22 km (13.2 miles) upstream from the dated bedrock. The other ponds in the Middle Popo Agie River drainage south and east of Wind River Peak, including the “Ice Lakes” ponds would likely also have been covered by ice then (e.g., Wind River Peak Ponds, “Ice Lakes” ponds).

Exposure ages for moraine boulders high in the North Popo Agie River drainage attest to a very different glacial history. A boulder in Lizard Head Meadows had a beryllium-10 age of 17,600 years ago (standard deviation of 1,700 years) (Dahms and others, 2018). This location is less than 5 km (3 miles) from the Continental Divide and implies that the valley glacier in the North Popo Agie Canyon had retreated 27 km from its terminal moraine in 4,000 years (Dahms and others, 2018). Such rapid melting could have exposed many lakes, such as those in “Smith Lake” Creek Canyon and High Meadow Creek Canyon by 17,600 years ago. Given the different retreat rates of the Middle and North Popo Agie glaciers, speculating on when various upland ponds and lakes melted off is problematic.

About 2 km farther up valley from Lizard Head Meadows, boulders on the moraine below “Lonesome Lake” yielded ages of 15,100 and 16,100 years ago (standard deviation of 1,600 years, mean 15,600 years) (Dahms and others, 2018). That this was the lower end of the North Popo Agie glacier while the Middle Popo Agie glacier still extended almost all the way to Sinks Canyon is surprising, to me. Dahms and others (2018) suggested the different behaviors of the glaciers could be due to different ice-shed areas or topography.

The glaciers’ last stand up against the Continental Divide circling Cirque of the Towers was also dated by Dahms and others (2018). 2 boulders on a moraine below the southern headwall of the Cirque gave beryllium-10 ages of 11,200 and 12,300 years ago (standard deviations of 1,100 and 1,300 years, mean 11,750 years). These ages are 1,000 or more years younger than those from the “Titcomb Lakes” moraine. The dated boulders were at 3,225 m (10,580′). The fairy shrimp-hosting Bivouac Lake has an elevation of 3,334 m (10,940′) and has a similar topographic setting (Bivouac Lake map). It is immediately below the Continental Divide at Atlantic Peak but is below an east-facing slope rather than a north-facing slope. More sun exposure may cancel out effects of the higher elevation. Fairy shrimp have maybe had 11,750 years to get there.

If they hadn’t melted off by 15,300 years ago, the ponds in the vicinity of “Coon Lake” (Little Sandy Overlook Pond map) would certainly have melted off by 11,750 years ago.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Exposure Ages of Moraines in Stough Creek Basin

In a serendipitous coincidence, Dahms and others (2018) provided ages on boulders in Stough Creek Basin (Deep Cirque Overlook Pond map) that constrain the appearance of fairy shrimp ponds that I visited there. Samples of glaciated bedrock and lateral moraine boulders along a west-east transect between Footprint Lake and Shoal Lake (Dahms and others, 2018, did not use these Wyoming Game and Fish Department names) give a somewhat consistent pattern of beryllium-10 ages decreasing with elevation on both sides of the basin as the ice melted down. A sample on the hill south of Cutthroat Lake at about 3,330 m (10,830′) gave an exposure of 14,800 years ago (standard deviation of 1,400 years) while a lower one just east of the creek gave 12,500 years ago (standard deviation of 1,300 years) (Dahms and others, 2018). This indicates the ice melted off the fairy shrimp-hosting Shoal Lake Northwest Pond and Stough Off Channel Pond by about 12,500 years ago and off East Side Cirque Pond at some time between 12,500 and 14,800 years ago. The transect extends west of these points up the ridge north of Deep Cirque Overlook Pond. The bedrock samples on the ridge above the pond had exposure ages of 18,300 and 18,400 years ago (standard deviations 1,800 and 2,000 years). Even though this indicates Deep Cirque Overlook Pond could have been colonized much earlier than Stough Off Channel Pond, that seems unlikely. With the large lakes in Stough Creek Basin still covered by ice, what bird or other animal dispersal agent would want to visit the basin?

Moving up canyon (Cinquefoil Pond map), boulders on a moraine south of Stough Below the Moraine Pond gave exposure ages of 12,700 and 13,600 years ago (standard deviations 1,200 and 1,500 years, mean 13,150) (Dahms and others, 2018). Although it is difficult to tell from the small-scale map in Figure 6 of Dahms and others (2018), I think these boulders are from the small moraine close to the pond and not from the monster moraine farther south (see photo below). Boulders on the smaller moraine below and north of the pond were found to have beryllium-10 ages of 13,900 and 17,200 years ago (standard deviations of 1,500 and 1,700 years). The older age could be due to inheritance of beryllium-10 in a boulder that tumbled off a cliff above the glacier and ended up on the moraine next to boulders that had been below the ice. The younger age fits better with the 2 ages for the moraine less than 200 m (660′) away on the other side of Stough Below the Moraine Pond and with the absence for such old ages for the moraines above Footprint Lake (Deep Cirque Overlook Pond map) (additional ages in Dahms and others, 2018). Either way, Cinquefoil Pond would have been ready for its fairy shrimp by 13,150 years ago and Boulder Bog Pond perhaps a little sooner.

That ice remained on the floor of the basin at 12,500 years ago indicates that it had become stagnant and detached from nearby cirque glaciers. Dahms and others (2018) suggested the Stough Creek Basin glacier became detached from the glaciers overlying Canyon Lake and Stough Below the Moraine Pond by 16,000 years ago and remained stagnant until melting off by about 12,500 years ago. Such stagnant ice would have impeded colonization of ponds above the valley floor even if they were not covered by ice.

The pond in the middle distance is Stough Below the Moraine Pond. The nearer pond at left is Cinquefoil Pond. 3 moraines are visible. The low ridge of rock on the near side of Stough Below the Moraine Pond is the oldest. 2 boulders from there have exposure ages of 13,900 and 17,200 years ago. The darker, higher ridge of rock on the far side of the pond has boulders that were exposed 12,700 and 13,600 years ago. There is a small snowbank at the bottom of the left end of this 2nd moraine. There is a pond-like depression behind the 2nd moraine but I didn’t find any water in it. The very high, steep pile of rock behind the 2nd moraine is the 3rd and youngest moraine. Aerial imagery of The National Map currently shows a partially ice-covered pond behind the 3rd moraine. The 3rd moraine may have taken its final form at the end of the Little Ice Age (see below).

As reviewed by Dahms (2002), some Wind River Mountains moraines were attributed to glacial advances between 10,000 and 2,000 years ago. Some of these attributions have been contradicted by more recent beryllium-10 dating (Dahms, 2002). After obtaining pre-10,000 years exposure ages on the “Alice Lake” age-correlative moraines in Stough Creek Basin and Cirque of the Towers, Dahms and others (2018) noted “it is possible that evidence no longer exists for early- to mid-Holocene glacial events in the southern Wind River Range” (i.e., 10,000-5,000 years ago). This is consistent with Jones and others’ (2023) finding that bedrock adjacent to Mammoth Glacier had been buried by ice only for the last 1,000 years since 11,000 years ago (see above).

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Little Ice Age Glaciation

The Little Ice Age cooling from about 1200 (or 1300, according to others) to 1850 was sufficient to spur glacial advances world wide (Lowell, 2000). Little Ice Age advances in the Wind River Mountains appear to have been minor in that they did not override “Alice Lake” or “Titcomb Lakes” moraines. The Little Ice Age moraine below Mammoth Glacier is less than 500 m (1,640′) from the 2002 ice margin (Davies, 2011). Mammoth is southwest of Gannett Peak and is the largest glacier west of the Continental Divide.

In some cases, the Little Ice Age moraines are coincident with 1930 ice margins. According to Pochop and others (1989), “Dinwoody and Gannett Glaciers had readvanced by 1930 to their positions at the end of the Little Ice Age (Denton, 1975)”. I haven’t tried to find Denton’s book to verify this. Gannett Glacier is the largest in the range. An advance up to 1930 could have been caused by increased precipitation even as temperatures warmed. Pochop and others (1989) mapped the glaciers’ retreat from 1950 to 1983 using aerial and ground photographs. The 3 lobes of Gannett Glacier retreated 200 m (660′), 360 m (1,180′), and 500 m (1,640′) and the main lobe of Dinwoody Glacier pulled back 220 m (720′) during the period, as measured by me on Figures 2 and 3 of Pochop and others (1989, p. 5, p. 7). My measurements are subjective and I excluded a shallowly covered ridge that melted off between 1966 and 1983. Because tree ring data indicate that the period 1942-1954 was “especially favorable” for growth (Pochop and others, 1989) (i.e., wet), the 1950 glacier margins were probably close to those of 1930 and, hence, to the maximum advance of the Little Ice Age.

Recent work by Jones and others (2023) provides more information on the Little Ice Age extent and subsequent retreat of Mammoth Glacier. First, their maximum Little Ice Age extent of the glacier is slightly larger than that of Davies (2011) so that the retreat from the maximum to the 1966 ice margin (from topographic maps) was 560 m (1,840′) and that to the 2021 ice margin (based on satellite imagery) was 1,000 m (3,280′) (as measured by me from their Figure 1). Second, these distances indicate average retreat rates of 4.8 m (16′) per year from 1850 to 1966 (or 15.6 m, 51′, per year from 1930 to 1966) and 55 m (180′) per year from 1966 to 2021. The finding that bedrock adjacent to the 2021 ice margin of Mammoth Glacier was exposed for 10,000 of the last 11,000 years (Jones and others, 2023) indicates that all but a few, if not all, glaciers had disappeared from the Wind River Mountains prior to Little Ice Age glaciation.

The Little Ice Age glaciers necessarily destroyed any ponds that were previously up hill from the current positions of their terminal moraines. Due to the retreat of glaciers in the Wind River Mountains since 1930, or before, and especially in the last 30 years, there are current ponds behind some Little Ice Age moraines. They or may not have been there before the Little Ice Age advances. Examples include ponds at the head of Atlantic Canyon above Upper Saddlebag Lake (photo), at the head of Stough Creek Basin, North of Lizard Head Peak, below Knifepoint Glacier, below Lower Fremont Glacier, below the remaining pieces of Sacajawea Glacier, where the northern part of Minor Glacier used to be, and “Iceberg Lake”, which has doubled in size and now occupies what was the northern third of Sawtooth Glacier. These ponds were identified using aerial imagery and topography of The National Map. The first 3 are located on massive piles of rock rubble at the heads of cirques; the others are where glaciers were previously shown on 7.5-minute topographic quadrangles. The location of the pond north of the glacier north of Wind River Peak is both (see below). Ponds that were adjacent to ice shown on the 1960s topographic maps may also be impounded by Little Ice Age moraines. Such ponds include the previously mentioned “Iceberg Lake”, and ponds adjacent to Mammoth and Stroud glaciers. For these ponds, any pre-Little Ice Age fairy shrimp populations were lost and the colonization clock has been reset to as recently as 1930.

The small pond north of Wind River Peak between a glacier and its moraine. The fact that the pond is still in contact with the glacier suggests that retreat from the moraine was recent, possibly since 1930. There is no moraine above the one below the pond. Therefore, the moraine probably formed during the Little Ice Age.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Summary of Pond History

To summarize the pond history of the Wind River Mountains based on beryllium-10 dating of glacial materials, essentially all of the mountains were covered by ice at the maximum extent of the Pinedale glaciation about 23,000 years ago. Glaciers had begun to retreat by about 19,000 years ago. Lower elevation lakes on the west side of the divide, like “Fremont Lake”, “Willow Lake”, and “Half Moon Lake” had been deglaciated by this time or soon after. Glaciers in different valleys retreated at different rates: 27 km by 17,600 years ago in North Popo Agie River valley but only 6 km by 15,400 years ago in Middle Popo Agie River valley. By 15,600 years ago, the North Popo Agie glacier had retreated another 2 km (1.2 miles) to above “Lonesome Lake”. At about the same time, glaciers had melted off “Temple Lake” on the west side of the divide. Quite a few ponds had probably been exposed by this time but identifying which ones is guess work. At 13,300 years ago, glaciers had pulled back from high elevation lakes like “Titcomb Lakes” and “Alice Lake” and probably from most other lakes and ponds in the range. Retreat from a well shaded Cirque of the Towers moraine at 11,750 years ago signaled melt off for essentially all Wind River Mountains ponds.

Glaciers in the Wind River Mountains expanded during the Little Ice Age but they didn’t get far. Where measured, Little Ice Age moraines are not more than 1 km (0.6 mile) below early 2000s ice margins. Regardless of when glaciers reached their maximum extents, they may have remained close to those limits until about 1930. Only a few ponds could have been affected by the Little Ice Age advance.

Ponds above Little Ice Age moraines may not be ready for fairy shrimp yet. High elevations and possible contacts with ice would keep water temperatures low. Fairy shrimp can hatch at 5 C (“Temperature Effects on Fairy Shrimp Hatching” on the Resting Eggs of Fairy Shrimp and Their Hatching page) but their growth is slow and they may not produce many eggs (“Temperatures of Fairy Shrimp Habitats” on the Habitats of Fairy Shrimp page).

The recent trend of warming temperature and decreasing ice cover at least since 1930 would be good for fairy shrimp colonization as higher ponds become warmer and additional ponds form in the footprints of disappearing glaciers, such as “Iceberg Lake” and the one below Knifepoint Glacier. There is also the possibility of negative impacts due to warming if that allows invasions by frogs, salamanders, or other predators. Although a warming climate could be good for fairy shrimp, it is bad for pikas, which are cute and furry and and have a squeaky voice.

All in all, glaciation has made the Wind River Mountains a great place for fairy shrimp. The huge negative impact is that the scenery attracts people and people have stocked the lakes with fish.

Back to Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains

Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

What Is Fish-stocking?

Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Wind River Mountains?

If the stocked fish die without establishing a reproducing population, can previously eliminated invertebrate species recover?

What happens when fish become residents of a previously fishless lake in the Wind River Mountains?

What experimental evidence can be used to determine the effects of fish-stocking on fairy shrimp?

What other experiments with fish and invertebrates can be used to infer what happened to fairy shrimp in stocked lakes?

Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

What Is Fish-stocking?

Fish-stocking is the dropping of 1 or more live fish into a body of water. Fish management agencies typically dump a couple hundred to a few thousand, small (7-18 cm, 2-7″) fish at a time into a mountain lake from a helicopter. The dumped fish are species that people like catching and are usually obtained from a state-supported fish hatchery. They are exotic to the receiving lake unless the fish management agency is trying to restore a native species that was wiped out by exotic fish. Larger fish that don’t need to grow as much before they become “catchable” are dumped in some cases. Most mountain lakes that are currently being stocked in the western United States are stocked repeatedly on periodic (e.g., every 2-4 years) or irregular schedules because the fish populations don’t reproduce. Individuals have also stocked lakes on their own initiative using the means at their disposal. Before helicopters, this included packing large cans of water with fish on horses. Individuals have also dumped bait fish, such as minnows, into lakes rather than carry them home or back to their water body of origin.

The effects of fish-stocking extend beyond the lakes where the fish were dropped. If one lake in a basin with several lakes above the fish-blocking topography were stocked, the fish would move to adjacent lakes through connecting streams to the extent possible. Those lakes could also be considered “stocked”.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

Most of the lakes and ponds in the Wind River Mountains are above waterfalls or steep rapids that fish cannot climb. Their natural states were fishless. Most people don’t value naturalness. They value well known and accepted recreational activities like fishing. Native aquatic invertebrates may just be creepy creatures to them. Lakes with fish might even seem more natural because lowland lakes and reservoirs all have fish. When questioned about their recreational activities, people who reply “I went fishing” are likely to garner more respect and be more likely to elicit a favorable reply than those who reply “Oh, I hiked around and admired the scenery”.

State governments have been responsible for most stocking in the United States. In the early days, private individuals stocked fish wherever they wanted to. At least in Wyoming, it is now illegal to stock fish without the authorization of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department. Violators can be punished by a fine of up to $10,000 and by up to 1 year in jail (2025 Fishing Regulations). There is no down side for states; they can’t be held responsible for wrecking ecosystems. Only if a species involved is threatened or endangered does the Endangered Species Act come into play. That Act is not relevant for naturally fishless alpine lakes because fish don’t eat birds or pikas and federal and state agencies generally don’t look beyond vertebrates.

The States’ goal for fish-stocking was and is to attract tourists who will spend money in the nearby towns and to satisfy the demands of residents who are now accustomed to fishing in alpine lakes. People who fish at stocked lakes are blithely unaware of the economic and environmental costs of fish-stocking. They paid only for a fishing license which costs the same regardless of where they fish. Most don’t even know if a lake was stocked. They almost certainly don’t know or care what animals lived in the lake before it was stocked.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

A 1988 compilation of estimates supplied by fish and wildlife agencies in the western United States (Colorado and states west) indicated that of approximately 16,000 mountain lakes, 60% (9,600) have fish but less than 5% (800) had fish before fish-stocking began (Bahls, 1992). Even lakes with native fish have been stocked so fish and wildlife managers thought that only 1% (160) of lakes have only native fish. Larger lakes are more likely to sustain populations of exotic trout. Fish and wildlife managers guessed that less than 5% of lakes larger than 2 hectares (5 acres) and deeper than 3 m (10′) remained free of fish.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Wind River Mountains?

The story of fish-stocking in the Wind River Mountains begins with Finis Mitchell, although there may have been others. Finis Mitchell enjoyed fishing. He also loved hiking and riding and climbing the peaks of the Wind River Mountains. He started a fishing camp at “Mud Lake” on Big Sandy Creek in 1930. By then, he already knew most of the high elevation lakes lacked fish. For the benefit of his customers, other anglers in Wyoming, and maybe, in his mind, for the benefit of all humanity, he started the arduous task of stocking lakes by horseback. By his own account, Mr. Mitchell stocked 314 lakes with 2.5 million fingerlings (from the story at www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/finis-mitchell-mountaineer; this account is consistent with what I remembered from reading a book about Finis Mitchell in the 1980s). Mr. Mitchell ultimately received numerous awards for his work popularizing the Wind River Mountains and its newly fabulous fishing.

Finis Mitchell’s efforts were hugely successful. The stocked trout populations thrived. At some point, Wyoming legislators noticed and provided money for WGF to stock even more lakes. By the 1970s, helicopters were being used. Employees of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department (WGF) were well aware of the effects of fish-stocking. In the 1980s, some in the Lander office told me that trout grew to huge sizes in the first few years after the first stocking event. They attributed the monstrous sizes to the abundance of invertebrate food. They did not know of any current or pre-stocking fairy shrimp populations.

Of “over 2,000 glacial carved lakes, ponds, and potholes” in the Bridger Wilderness, more than “500 are known to support fish” (Wyoming Game and Fish Department, 2013, Bridger Wilderness, A Guide to the Fishing Lakes). The Fitzpatrick and Popo Agie wildernesses have additional ponds, though probably less than 2,000 (EIGWUU). The WGF listed fish in ponds as small as 2 acres (0.8 hectares) (e.g., Lost Lake, WGF name, in the Boulder Creek drainage). A 2-acre square is small, only 295 feet (90 m) on a side. This illustrates the current pervasiveness of fish in the Wind River Mountains.

Use of helicopters for fish-stocking in the mountains of Wyoming has not been controversial but it conflicts with part of the Wilderness Act. Most of the alpine terrain in the Wind River Mountains has been designated as Wilderness by Congress. Although helicopters aren’t generally allowed in Wilderness Areas, Congress avoided angering states by including the following language in the Wilderness Act of 1964: “Nothing in this Act shall be construed as affecting the jurisdiction or responsibilities of the several States with respect to wildlife and fish in the national forests”. Such internal contradictions are a common feature of U.S. legislation. Congress could not even agree on the purpose of the act so it punted its responsibility and let the land management agencies take the crossfire from the public: “wilderness areas shall be devoted to the public purposes of recreational, scenic, scientific, educational, conservation, and historical use.” Although preserving native species might be included in the category “conservation”, it obviously doesn’t stand a chance against recreational and historical fishing.

Many of the Wind River Mountains’ alpine lakes are on the Wind River Indian Reservation. As the Northern Arapaho and Eastern Shoshone tribes evidently prefer fishing to admiring native aquatic species, aquatic invertebrate populations there have fared no better. WGF’s offer to stock the Reservation’s alpine lakes by helicopter was too good to pass up. The state got another draw for rich tourists and the tribes got new unsustainable fish populations for tribal members to exploit and the opportunity to collect trespass/fishing license fees from non-tribal members.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

If the stocked fish die without establishing a reproducing population, can previously eliminated invertebrate species recover?

Insect species that have aquatic larvae commonly have adults that can fly. If fish wiped out a population in 1 lake, a surviving population in a non-stocked, non-connected lake or pond could recolonize it. Early success would depend on the source lake and the stocked lake being within the normal flying range of the adults of the species. If no populations of a species survive in a lake nearby, maybe gravid flying adults could be blown in by a storm. Depending on the frequency of such events, it could be a very long time before the stocked lake is recolonized. Knapp and others (2001) found that many clinger-swimmer insect species recovered after fish died out in stocked lakes and noted that mayflies can “disperse tens of kilometers”. Caddisflies didn’t do so well.

For crustaceans that produce resting eggs, like fairy shrimp and cladocerans, eggs remaining on the lake bottom could hatch and re-establish a population that had been eliminated by fish provided that sufficient eggs remain viable after the fish die out. Some resting eggs that are 15 years old can be hatched. It all depends on how long the fish live and how long the eggs remain viable under local conditions. The copepod Hesperodiaptomus shoshone and the cladoceran Daphnia middendorffiana reappeared in stocked lakes in the Sierra Nevada that became fishless but Knapp and others (2001) ignored rare species like fairy shrimp.

At “Bighorn Lake” in Banff National Park, Canada, the cladoceran Daphnia middendorffiana reappeared a year after trout were removed by gill-netting (Parker and others, 2001). It must have hatched from eggs that were about 30 years old. The copepod Hesperodiaptomus arcticus had not recovered within 3 years and its eggs were not found in the lake sediment (Parker and others, 2001). Daphnia pulex reappeared in “Snowflake Lake”, also in Banff National Park, even before the last brook trout died in 1984 (McNaught and others, 1999). H. arcticus remained absent through 1991. H. arcticus did recover after stocked fish died out in “Pipit Lake”, also in Banff National Park (Parker and others, 1996). H. arcticus eggs were common in the sediment of that lake. Eggs collected from sediments as deep as 5 cm (2.0″) hatched in the laboratory. It was inferred that a larger population of egg-eating amphipods in “Snowflake Lake” than in “Pipit Lake” accounted for the disappearance of eggs there although a smaller pre-stocking egg reserve was also possible (Parker and others, 1996).

The reappearance of Daphnia melanica in a Sierra Nevada lake within a year of trout removal was also attributed to resting eggs (Latta and others, 2010, abstract only).

If the fish live longer than the eggs of fairy shrimp remain viable, then a new population could only be established by recolonization (see Fairy Shrimp Dispersal and Colonization). Recolonization rates are not known. I have yet to find any estimates in the scientific literature.

The key is dispersal. In deserts, resting eggs can be carried to new ponds from dried pond bottoms by wind. Recolonization of alpine lakes would almost certainly require animal dispersal agents. Resting eggs could conceivably get stuck in marmot fur at a nearby lake with fairy shrimp and be carried to the newly fish-free lake. The probability of that happening is, no doubt, low. If marmots never walk into lakes, the probability is 0. Birds can also be dispersal agents and would be the only likely agent if the nearest possible egg source is many kilometers away. The probability of bird dispersal is also low and could be driven lower by another factor – how many lakes still have fairy shrimp. Recolonization by bird dispersal almost requires that the bird, such as a duck, eat a female with an egg-filled ovisac in the source lake and defecate in the recipient lake. The more eggs defecated into the recipient lake, the more likely recolonization will be successful. If an area has lots of lakes with fairy shrimp or other invertebrate duck food, then ducks are likely to visit the area and stop at several lakes to find the most food. If an area has only a few lakes with duck food, ducks may not bother to visit the area at all. Recolonization then becomes exceedingly rare. My 2 estimates of the frequency of fairy shrimp ponds, 10% in 1 area and 16% in another (see What Can We Learn from the Ponds in the Wind River Mountains?) are not encouraging. Worse, I visited more than 90 ponds before I found ducks staying at a lake with abundant invertebrate duck food, Lower Indian Pass Lake.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

A related question is: Would fish management agencies continue to stock a lake with a non-reproducing fish population? The answer to that question is Damn Right! WGF even gloats over how much re-stocking it does. It tries to gain the public’s admiration, and maybe more funding, by posting numbers and sizes of fingerlings dropped in stocking events on its web page. You can even download a spreadsheet with stocking by fish species, county, or lake. Fish stocking reports are at https://wgfapps.wyo.gov/FishStock/FishStock, which is a form with drop-down menus. Results of fish surveys and photos of big trout held by a smiling employee are routinely published by WGF online. A 2019 newsletter for the Lander office has “Wind River Helicopter Stocking” on page 1. 73,365 golden, cutthroat, rainbow, brook, and tiger trout were dropped in 28 lakes in National Forest Wilderness Areas and in 12 lakes in the Wind River Indian Reservation (wgfd.wyo.gov/WGFD/media/content/PDF/Fishing/LR_ANGLERNEWS_2019.pdf). The article noted that “[m]ost wilderness lakes support wild, naturally reproducing fish populations” but that the stocked lakes do not and must be stocked every 2-4 years. Does that mean fish are dying faster than people can catch them?

WGF also has an online map that identifies which species of fish have been caught at which lakes. For the lake guide, go to https://wgfd.wyo.gov/fishing-boating/places-fish-wyoming and click on the link to the “Interactive Wyoming Fishing Guide”. Click on the lake for a pop-up with lake depth and fish species. If you want to find fairy shrimp, you could use the map to identify lakes to avoid.

WGF doesn’t just restock lakes to keep the fish numbers up. It also tries to keep body sizes up. “Tiger trout were stocked in Upper Silas Lake in 2014, 2016, and 2018 to improve a stunted brook trout population. The goal of stocking tiger trout in Upper Silas Lake is to reduce the number” of brook trout by predation and thereby increase the sizes of the survivors “as well as create a tiger trout fishery.” (“Tiger Trout in the Wind River Mountains”, June 26, 2020 news release by the Lander Regional Office; https://wgfd.wyo.gov/Regional-Offices/Lander-Region/Lander-Region-News/Tiger-trout-in-the-Wind-River-Mountains) The productivity of some high mountain lakes is evidently so low that brook trout don’t have enough to eat. Even so, they keep reproducing. Consequently, some lakes have lots of small brook trout, which people don’t like.

Small trout are not restricted to the Wind River Mountains or to Wyoming. Idaho has the same problem. “Brook trout also can become so abundant that the size of fish in the population becomes stunted and unappealing to anglers. . . . One new tool that biologists with the Idaho Department of Fish and Game have been investigating is stocking alpine lakes with super-male brook trout”. Super-male individuals have 2 Y chromosomes and consequently produce only male offspring (https://idfg.idaho.gov/blog/2021/08/can-super-male-brook-trout-improve-angling-alpine-lakes). Without females, the brook trout populations decline. Individual fish have more to eat and get bigger. Of course, if the population gets dangerously low, it would be restocked with fish raised at state expense.

In Banff National Park, Canada, brook trout in “Bighorn Lake” had very slow growth rates (Parker and others, 2001). Older individuals became large but were in “poor” condition. Parker and others (2001) noted “Severe emaciation of unexploited salmonids in alpine systems has been reported elsewhere”. This government perpetuation of failed fish ecosystems for recreational purposes makes the Endangered Species Act seem almost rational.

The answer to the original question above is “probably not”. WGF’s commitment to restocking and the spread of fish from stocked lakes to others via connecting streams would seem to make re-establishment of eliminated invertebrate populations very difficult. Rarity or lack of dispersal agents for fairy shrimp eggs such as birds impose further severe constraints on recolonization.

In the Sierra Nevada, the return of mountain yellow-legged frogs to some alpine lakes that previously had fish without assistance is considered a big success (Knapp and others, 2001). The presence of a lake with frogs within 1 km (0.6 mile) of the “stocked-now-fishless” lake was the determining factor. What are the determining factors for fairy shrimp?

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains

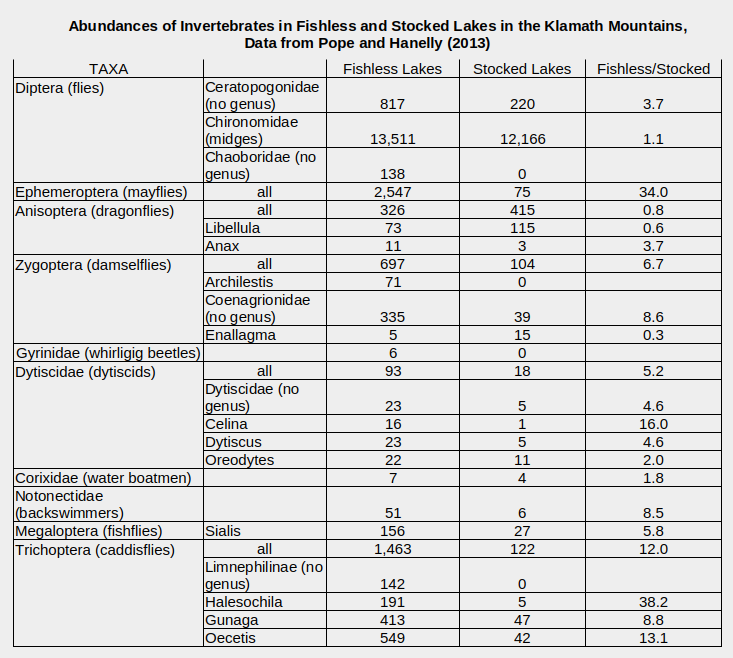

What happens when fish become residents of a previously fishless lake in the Wind River Mountains?