For how I arrived at this point, see In The Beginning

Fairy shrimp swimming in a peanut butter jar at Bivouac Lake.

In fall 1986, I hiked back to Bivouac Lake about a year after I had first seen fairy shrimp to collect specimens for identification. In February 1987, I finally got around to mailing them off to Denton Belk (DB), on the suggestion of Arthur Shoutis (see In The Beginning). DB had done research on fairy shrimp in the southwestern United States and had published an identification key for fairy shrimp (Belk, 1975; for citations, see the References page). He was obviously more than qualified to tell me if the specimens were fairy shrimp and, if so, what species they are. However, I really didn’t know what to expect. Maybe he would be too busy to respond to some ignorant wahoo from Wyoming. At this time, I wasn’t receiving responses to most of my job applications so that seemed like a likely outcome in this case, too. After all, it had been a couple of years since Arthur Shoutis had written him.

To my surprise, I received a 2-page letter from DB within a week. He identified the species in Bivouac Lake as Branchinecta coloradensis and enclosed copies of a few relevant journal articles for me to read. He asked for more specific location information. He answered all my questions, including advice on how to keep fairy shrimp in captivity. Unfortunately a 10-15 gallon, temperature-controlled aquarium was beyond my means. He also wrote “samples of other species or populations will be most appreciated . . . In time, my collection will be placed at the Smithsonian Institution.” So maybe my collecting would have some scientific value. I was hooked. DB even concluded with “If I can be of any additional help . . .” What luck! I could pursue my interests and this guy could, and would, answer my questions.

By the end of April, I had lined up a new job and it wasn’t in Wyoming. However, it didn’t start until September. I wasn’t likely to get any more work as a day-laborer shoveling snow (believe it or not, the Lander hospital had a flat roof) and I knew of no other opportunities. Wyoming was still deep in the throes of the oil bust. The bumper sticker “Oh God, give us one more boom; we won’t blow it this time” was popular. Could I think of anything to do in the next 4 months? Spring 1987 became a whirlwind of fairy shrimp discovery.

In early May, I began finding fairy shrimp in ponds out in the sagebrush of the Antelope Hills. This was surprising for 2 reasons. One, I hadn’t been aware that there were ponds out in the rolling hills of sagebrush that are so common in Wyoming. Two, the ponds, though ephemeral, had abundant animal life, including fairy shrimp in many cases. By the end of June, I had visited 31 ponds in the Antelope Hills and northern edge of the Great Divide Basin and collected 13 samples of fairy shrimp specimens (2 each from “Coyote Lake” and Bull Canyon Pond). My search for ponds was facilitated by the purchase of 1:100,000-scale BLM maps from the BLM office in Lander for only $4 each. They only show the largest bodies of water, ephemeral or not, but that’s a start and they show the roads, which is critical.

Meanwhile, I was carrying around identification keys and journal articles which allowed me to identify avocets, phalaropes, coots, and grebes in “Coyote Lake” and elsewhere and some small aquatic animals, such as ostracods (crustaceans of the class Ostracoda; see Other Crustaceans You May Find with Fairy Shrimp), dytiscid larvae (insects of the order Coleoptera, family Dytiscidae; see Predators of Fairy Shrimp), and backswimmers (insects of the sub-order Heteroptera, family Notonectidae; see Predators of Fairy Shrimp). I even became confident in identifying the little black specks swimming with a jerky motion as copepods (crustaceans of the class Maxillopoda, subclass Copepoda; see see Other Crustaceans You May Find with Fairy Shrimp). Finally, with the help of Arthur Shoutis’s binocular microscope, I tried my hand at identifying fairy shrimp with the keys of Belk (1975), Lynch (1964), and Pennak (1953 edition). I was becoming something of an amateur biologist. This is not something I had ever dreamed of doing but I saw no reason to resist the urge to learn about fairy shrimp.

I began my July 7, 1987 letter to DB with “You wrote, in your letter of March 2nd, that you would be interested in other anostracan specimens. I hope you meant it.” I then rambled on for 3 1/2 pages. I even speculated, in spite of my very limited knowledge, on why some ponds had fairy shrimp and some didn’t. I went so far as to request tips on field identifications of fairy shrimp. Although identification keys commonly use microscopic details of the male antennae II, maybe there was something visible (or visible with a 10x magnifying glass), like the length or shape of the distal segment, that would work in most cases. What a presumptuous newbie I was!

With Help from Denton Belk – top

The August 9, 1987 reply from DB was very gracious, and encouraging. He even thanked me for the “very interesting and valuable collections.” But the real kicker was “You have discovered two new fairy shrimp records for Wyoming – Streptocephalus seali and Branchinecta mackini.” Then, “the unusual paludosa-like branchinectid from Bull Canyon Pond may be a new species.” That is certainly more, in scientific value, than I could have hoped for in my first 2 months of fairy shrimping. Of course, the fact that I had found 2 species that had not previously been reported from Wyoming was also a reflection of the paucity of previous fairy shrimp work in Wyoming. They’re not popular with biologists. DB countered my speculation based on a very small number of ponds that amphipods and snails could prevent or eradicate fairy shrimp populations by writing that he had found fairy shrimp with both. With regards to my idea that wave action on the sandy shores of the ponds in Killpecker Dunes could abrade and destroy fairy shrimp eggs, thus accounting for the absence of fairy shrimp there, DB enclosed a relevant journal article and wrote that “eggs are tough and are not likely harmed by wave or wind action.” DB also described a method to tranquilize fairy shrimp with fizzy soda water first to prevent the convulsions when they are placed directly in alcohol. As for field identification, DB offered no encouragement. “I would never trust an identification without going to the microscope.” Finally, he explained that the pairs of stuck-together clam shrimp I had seen in Chinook Pond on June 28, 1987 were copulating and may remain stuck together for “several minutes”. After all that, he did not need to add “I look forward to more collections as you have time and interest in making them.”

The revelation that I had found B. mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi) in 3 ponds caught my interest. Brown and Carpelan (1971) had written an information-packed article on the B. mackini of “Rabbit Dry Lake” in the Mojave Desert. Their brief description of Branchinecta gigas, which was peripheral to their research, as a unique fairy shrimp carnivore that eats B. mackini and is much larger (Pennak, 1978, gave a length of 5-10 cm, or 2-4″) stuck with me. What would it be like to see fairy shrimp that big? Did I have a chance in Wyoming? In my September 7, 1987 letter to DB, I went so far as to write, half jokingly, that “I won’t rest until I find the monster fairy shrimp, B. gigas.” To be sure, I would be paying more attention to the large playa lakes in the Great Divide Basin.

Before I received DB’s response to my July letter, I went on another fairy shrimp search in early August. I wanted to take more photographs of the fairy shrimp in Bivouac Lake and find some in other alpine ponds. Imagine how much fun it would be if fairy shrimp were common throughout the Wind River Mountains. Of course, a backpack trip into the Winds is a great idea even without the fairy shrimp interest. I lucked out at “Coon Lake”. Although the lake has been stocked with fish, I found several small ponds west and south of the lake and most had fairy shrimp. Gorgeous scenery, spectacular flowers, – or is it the other way around? – and fairy shrimp.

“Coon Lake”, as another day of fairy shrimping dawns. Ponds nearby have fairy shrimp; did the lake have fairy shrimp before being stocked with fish?

About a week after I got back from my trip to the Wind River Mountains, something really unexpected happened in my already surprising adventure of fairy shrimp discovery. I was hiking in the Granite Mountains and came across a small puddle on some rocks in the sagebrush. It must have come from a recent thunderstorm as any snow was long gone from this elevation, i.e., this was a stroke of luck. I had by then read about fairy shrimp occurring in “rock pools”. I had never seen a rock pool before. Maybe this was one. The water was only 12 cm (5″) deep. Could it have fairy shrimp? I leaned forward, hands on knees. There were fairy shrimp. Wild Horse Rock Pool was my first rock pool and it had fairy shrimp, in the middle of the summer. It’s almost embarrassing to write this. If I were making this story up, I certainly wouldn’t put fairy shrimp in the first rock pool. Maybe the third, or fifth. It would make a better story to reward the fairy shrimper for persistence; the first is too easy. Anyway, hiking around Tin Cup Mountain, I found other rock pools and most had fairy shrimp. There’s a good chance rock-pool fairy shrimp are different species than alpine fairy shrimp so I collected more specimens for DB.

Can you believe this has fairy shrimp?

After moving and starting a new job, I sent DB 5 more samples on September 7, 1987, 3 from alpine ponds and 2 from rock pools. In my letter, I thanked DB for his responses to my questions and speculations. He was really being far more helpful than I had any reason to expect. I had not detected any hint of dismissiveness in his letters in spite of my minimal understanding of fairy shrimp and limnology. I tried to entertain him with brief accounts of finding the fairy shrimp in the ponds by “Coon Lake”; of the elusive, deep-swimming females in Bivouac Lake; and of collecting specimens from the rock pools with a cooking pot because I hadn’t thought to take my net.

DB sent me more fairy shrimp articles in his September 23, 1987 letter. That saved me from trying to track them down in a university library and burning time photocopying them. He told me I had found both Branchinecta packardi and Branchinecta lindahli, which are known to inhabit rock pools. He explained that 2 fairy shrimp species populate the ponds and rock pools at Enchanted Rock, in central Texas. B. packardi has a faster growth rate and prefers cooler temperatures so it dominates in the rock pools. Streptocephalus texanus prefers warmer temperatures but grows slower so it only occurs in the larger ponds, which don’t evaporate as quickly. He sent me some fairy shrimp eggs so I could see how tiny they are but wrote that he had not been able to hatch these. DB also wrote that he had specimens of “what appears to be a new species of Streptocephalus” that Francis Horne had collected in Wyoming in 1965 (same Horne as Horne, 1967; see References page). He asked me if I would collect some more specimens from the same pond to help with identification of the species. I agreed and put the southern Laramie Basin on my list of places to check for fairy shrimp.

By the end of September, I had received and looked through all the photographs I had taken over the summer. I was impressed by the scenery and the variety of ponds I had found fairy shrimp in. I was also gratified that I had been able to take a few good photographs of the fairy shrimp themselves. As a result, I had prints made and put together a scrap book. I thought the photographs were something that DB would enjoy looking at and it would also give him a much better understanding of the ponds where I had found fairy shrimp. I don’t think he had ever been to Wyoming. I mailed the scrap book off to DB but, still feeling poor, I asked that he mail it back. DB liked it and diligently returned it.

With Help from Denton Belk – top

I didn’t have much time for fairy shrimp searches in 1988 but I hit the southern Laramie Basin and made a quick swing through the Great Divide Basin in search of the giant, translucent fairy shrimp. I think B. gigas is at least as good an excuse for roaming the wilds as Captain Ahab’s great white whale. Horne’s Pond XII, which had previously hosted a possibly new species, didn’t have fairy shrimp but 3 of 6 nearby ponds did. I collected a sample of fairy shrimp from 1. In the Great Divide Basin, my primary target was the very large “Lost Creek Lake” playa. It had very shallow water when I arrived but I couldn’t find fairy shrimp. Part of the problem was that the mud was so sticky that I was staggering and splashing around like a drunk, especially if I stood in one place too long while testing the water with my hand net. A few of the “intermittent lakes” on the 1:100,000-scale BLM map that I visited were dry but I did find fairy shrimp in 2. I collected samples from both.

The shocker of Mud Springs Pond #1. Recently precipitated white minerals cover the shore and islands and indicate the water has a very high TDS that would be toxic to most aquatic animals. There is a dark reddish scum in the water that looks like some kind of algal or cyanobacterial red tide. There is also a dark gray slime along the shoreline rich in organic matter of some kind. The pond has a strong odor that reeks of decay. Compared to the alpine ponds I was familiar with at the time, this is the twilight zone. But the avocet (on island above center) knows. The dark reddish scum is actually a mass of fairy shrimp. The wind has pushed them to this side of the pond and has even blown some out of the water and stacked them in low heaps.

Due to DB’s interest in the new paludosa-like fairy shrimp in Bull Canyon Pond, I stopped there after my transit of the Great Divide Basin. There was only a small puddle of water and it lacked fairy shrimp. I collected several pounds of dirt in hopes that it would have fairy shrimp eggs that I could hatch and sample later. After the weather cooled off where I lived, I put the dirt in a 5-gallon (19 liters) bucket and added water. After a couple of weeks, it had 1 fairy shrimp, 2 copepods, and something that might have been an insect larva.

I mailed DB 1 sample from the southern Laramie Basin and 2 from the Great Divide Basin on November 19, 1988. I told DB I was a “serious student” of Anostraca because I had spent $10 photocopying the 200 pages of Linder (1941) at a library. He actually agreed and sent me more photocopied articles for my “anostracan literature collection”. The specimens from Mud Springs Pond #1 were quite different from other fairy shrimp I had collected. It turned out that they were of the genus Artemia, which are commonly referred to as “brine shrimp”. Due to the remarkable appearance of Mud Springs Pond #1, I sent DB a photograph and this time I told him he could keep it.

In his letter of December 4, 1988, DB gave a very brief explanation of why he didn’t assign a species name to the Artemia specimens from Mud Springs Pond #1. “The North American species are a complex of an as yet undetermined number of sibling species reproductively isolated in nature by adaptation to habitats of very different water chemistry (Bowen, et al. 1985: J Crustacean Biology 5:106-129).” He proposed that if I collected some dirt from the shore of the pond, he would send it to S. Bowen so that she could hatch the eggs and determine the species. DB also humored my interest in Branchinecta gigas: “They are fantastic animals.”

1989 proved to be relatively productive on the fairy shrimp side of things although finding time was tricky. I tried again to find the possibly new species of fairy shrimp in Horne’s Pond XII and Bull Canyon Pond but without success. Some ponds in the Antelope Hills that had previously had fairy shrimp, including Bull Canyon Pond, were dry. I had better luck in the Granite Mountains. Some of the “soda lakes” I visited had fairy shrimp and I found a few more rock pools with fairy shrimp. In August, I finagled 3 days for a trip into the Wind River Mountains west of the divide. One of the shortest routes to the high country was from Boulder Lake trailhead so that’s where I went. I peered into lots of ponds but found fairy shrimp in only 3. This at least confirmed my hypothesis of a widespread distribution in the Winds but it also indicated fairy shrimp were uncommon. Nonetheless, that gave me sufficient justification for even more backpacking trips to glacial wonderland. On drives going to and from Wyoming, I stopped in the Snowy Range and found fairy shrimp in both ponds I looked at. I also visited rock pools in the southern Laramie Range next to I-80 east of Laramie where a friend had seen something in the water. By the end of the summer, I had 15 samples for DB to identify and add to his collection. Where I had seen Artemia, I also collected dirt samples that DB could send to S. Bowen.

Of the samples I mailed to DB on October 1, 1989, DB identified 4 “soda lake” Artemia populations, 5 Branchinecta lindahli rock pool populations, another Branchinecta coloradensis population in the Wind River Mountains, another Branchinecta mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi) population in the Antelope Hills, a Branchinecta paludosa population in the Snowy Range (Horne, 1967, had also reported B. paludosa from the Snowy Range), and 3 Branchinecta campestris populations in the Granite Mountains. In response to my questions, DB confirmed that B. campestris inhabits high-TDS water and can occur in the same ponds as Artemia. He sent me a photocopy of Lynch (1960) with more details about B. campestris. DB replied that others have also reported 2 Artemia males clasping the same female at the same time but also mentioned that “there have never been any detailed studies made of Artemia mating behavior”. He also sent me a preprint of Eng, Belk, and Eriksen (1990) on California anostracans, which was the culmination of a 9-year project.

With Help from Denton Belk – top

1990 was a dry year for Wyoming and I had precious little time to spare for fairy shrimping. Horne’s Pond XII and Bull Canyon Pond were again dry and “Coyote Lake” was also dry. My only samples were from 3 rock pools at 1 location in the Granite Mountains. But what a location Lankin Dome is. I first visited the area in 1989 after a guy at the BLM office in Lander told me that students on a National Outdoor Leadership School climbing course had seen animals in rock pools on Lankin Dome. I confirmed that fairy shrimp were present in some rock pools but didn’t have the means to collect any at the time. I went back better prepared in 1990. The first sample did not go well. The fairy shrimp literally got blown away as I was transferring them from the net to a bottle of soda water. Wyoming is almost always windy but that had never happened before. I was aghast at the fate of those blown out into the void from the summit of Lankin Dome. Never mind that I would have killed them anyway. I finally mailed the samples off on November 12, 1990 and got a reply from DB on December 1, 1990. The result was scientifically interesting as 2 of the rock pools had Branchinecta lindahli but 1 had Branchinecta paludosa. B. paludosa does not typically occur in rock pools. This also added to the distribution of B. paludosa: sagebrush steppe ponds in the Antelope Hills, alpine ponds in the Snowy Range, and now rock pools in the Granite Mountains.

Lankin Dome from the north. It is tempting to turn this into something heroic: fairy shrimper scales sheer precipice and risks death to reach fairy shrimp rock pools. In fact, the rock is hard and rough with innumerable foot and hand holds. The slope on the west side (right) is moderate enough to allow a walk-up, although hand holds provide welcome security. The greatest challenge is psychological. I avoided looking down. That fairy shrimp can take up residence on the summit of Lankin Dome does say something about the adaptability of the anostracan order.

I didn’t do any fairy shrimping in 1991 but wrote a letter to DB in November. In his November 27, 1991 reply, DB included an August letter that had been returned to him by the Postal Service. The August letter said Texas had had above normal rainfall and that DB was going to give a slide show on fairy shrimp, tadpole shrimp, and clam shrimp (all in the class Branchiopoda) at Guadelupe Mountains National Park, east of El Paso. DB had been cogitating on the rectangular pulvillus on the basal segment of the male antenna II of the Branchinecta lindahli specimens I had sent him and had come to the conclusion that it is not a good character for identifying species. Consequently, he thought that the specimens from Antelope Pocket Overlook Rock Pool, Turtle Rock Southwest rock pools, and 2 of the Lankin Dome Summit rock pools were not B. lindahli but a new species. He suggested I send him some dirt from those rock pools so he could hatch some fairy shrimp to study in more detail. DB considered the specimens collected from Big Skunk Granite Rock Pool and Little Skunk Granite Rock Pool in 1989 as bona fide B. lindahli. This was pretty interesting. Maybe I had collected 2 previously unrecognized species: the paludosa-like branchinectids from Bull Canyon Pond and the lindahli-like branchinectids from rock pools in the Granite Mountains and southern Laramie Range.

In his November letter, DB also mentioned he would be trying to collect fairy shrimp near Stone Mountain, Georgia, after attending the meeting of the Crustacean Society and American Society of Zoologists in Atlanta. A species had been collected from a rock pool there in 1935 but never reported since. In September, DB had visited with M. Simovich in California and became involved in working on fairy shrimp that might qualify for listing under the Endangered Species Act. Lucky for him, that meant he could actually get paid for identifying fairy shrimp rather than just doing it for fun and science as he does with the specimens I send him.

1992 had the driest conditions I had ever seen in Wyoming. Bull Canyon Pond and “Coyote Lake” were dry again. Ponds I visited in the Great Divide Basin were dry or lacked fairy shrimp. Rock pools in the Granite Mountains had lower water levels than I had seen before but it was enough for quite a few fairy shrimp populations. I collected another sample of the lindahli-like fairy shrimp from Antelope Pocket Overlook Rock Pool and a first sample from another rock pool. I also collected lindahli-like fairy shrimp again from the Turtle Rock Southwest rock pools in the southern Laramie Range.

Collecting dirt from rock pools for fairy shrimp eggs as DB had requested was not really practical at the time of my visits. First, the rock pools generally lacked fine-grained dirt although they often had a little coarse gravel. Second, they still had water. I would likely lose eggs pulling the mud out of the water. Instead, I collected live fairy shrimp from one of the Turtle Rock Southwest rock pools. Many of the females already had eggs but I caught a few males, too, in case they weren’t fertilized. I kept the fairy shrimp in a bucket of pond water at home. They died off over a period of about 3 weeks. I dried out the dead females and saved them. Most had eggs. After the last fairy shrimp died, I filtered the bucket water. I mailed the filter paper and the dried females to DB so he could try hatching any eggs that might be present.

In his letter of August 2, 1992, DB wrote that all 4 of the rock pool samples I had collected were of the lindahli-like variety. “This is clearly a new species.” If fairy shrimp were a hot topic of academic interest, or even a room temperature topic, a species in rock pools at a popular recreation spot less than 20 miles from the University of Wyoming and less than 75 miles from Colorado State University would already have been identified. Maybe there is yet some value in non-funded citizen science.

Antelope Pocket Overlook Rock Pool. Is this the home of a previously unrecognized fairy shrimp species?

With Help from Denton Belk – top

1993 was a near-normal precipitation year for Wyoming and consequently much wetter than the previous 5. I also had more free time than usual after a summer project fell through. First up was the Bighorn Basin. I had to go through Wyoming on the way back from Idaho so instead of taking the Interstate, I planned a more interesting route. Several stock ponds and reservoirs off the Nowater road lacked fairy shrimp but I did find fairy shrimp in one roadside pond off the highway west of Worland. I subsequently found fairy shrimp at 1 pond in the Wind River Basin, too. Assuaging the disappointment of the Big Horn Basin trip, the latter pond, Castle Gardens Storm Pond, was found to have both Branchinecta packardi and Branchinecta lindahli by DB. I camped in the Granite Mountains overnight. Snow the next morning caused me to head out instead of continuing to search for fairy shrimp. I’m pretty sure Wyoming snowstorms and fairy shrimping don’t mix well, even in June.

All was not lost though as I found several fairy shrimp ponds along the highway north of Rawlins. In the complex of ponds in the vicinity of Screeching Avocets Pond, every one I looked at had fairy shrimp. I collected samples from 3. 2 of those had both an Artemia species and a Branchinecta species, probably B. campestris (later confirmed by DB). What was speculation in 1989 had become fact for Wyoming. I spent so much time with the avocets and fairy shrimp that it was pitch-black by the time I got to Laramie. Horne’s Pond XII would have to wait for another year.

I tried Wyoming again about a week later and this time I struck it rich. Although Bull Canyon Pond was dry, most of the ponds that had previously had fairy shrimp in the Antelope Hills had water and fairy shrimp again. “Coyote Lake” was about the smallest I had ever seen it but that didn’t matter. New hatches were presumably caused by the influx of water or snowmelt onto the dry pond floor. Interestingly, the new generation of Branchinecta paludosa was now joined by a generation of the typical playa fairy shrimp, Branchinecta mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi). The 3 “Lewiston Lakes” had lacked fairy shrimp in 1987 but now they offered up a branchiopod bonanza. All 3 lakes had fairy shrimp, clam shrimp, and tadpole shrimp.

“Lost Creek Lake” and most other ponds I visited in the Great Divide Basin were still dry. However, “Brannan Reservoir” was tantalizingly close to a eureka moment. It was big, it had abundant branchinectids (I guessed Branchinecta mackini based on the clay-rich water). I searched long and hard but couldn’t find the giant, Branchinecta gigas. Another interesting find was the branchinectid in the roadside puddle of Sweetwater Mill Road Pond. DB later identified it as Branchinecta coloradensis. Not only did Wyoming have B. coloradensis in alpine ponds, it also had the species in desert ponds. This would not be too surprising to those familiar with fairy shrimp but it demonstrated to me that Bull Canyon Pond was not a fluke. B. coloradensis could occur in a variety of habitats in Wyoming.

Photo for DB. On the road from finding fairy shrimp in the clay-rich waters of “Brannan Reservoir” to finding them in a puddle along the Sweetwater Mill road, I was reminded of DB, who is a horseman as well as a biologist, by these wild horses. I had to stop. Maybe they had never seen a human get out of a vehicle before. They put on a little show for me, prancing back and forth, checking me out. It was a remarkable performance but I dared not clap.

For my final fairy shrimp trip of 1993, I headed into the Wind River Mountains. You shouldn’t be surprised. This time my primary target was Stough Creek Basin, which has numerous lakes and ponds and is relatively close to a trailhead southwest of Lander. I found 5 more ponds with fairy shrimp. I didn’t bother with the lakes due to the likelihood of fish. At least visually (i.e., not microscopically), all the fairy shrimp looked like the Branchinecta coloradensis in Bivouac Lake so I didn’t collect any samples for DB.

In my June 20, 1993 letter to DB, I noted that I had seen Artemia males latched on to branchinectid females. Is that a failure of identification or has a species identification method not evolved for Artemia? Because it was becoming so hard to keep track of all the ponds where I had found fairy shrimp, I compiled tables with pond locations, pond sizes, sample dates and so on and sent copies of those and a small-scale map to DB. In addition, I listed co-occurrences of fairy shrimp or of fairy shrimp and other branchiopods in the letter as much for my benefit as for DB’s. As I had the opportunity to examine the 1993 specimens with a binocular microscope but still had trouble identifying all the features referred to by Belk (1975), I decided to sketch the differences of the distal segments of the male antennae II as a cheat-sheet for species identification. I included a copy for DB’s comments.

As usual, I couldn’t help but discuss aspects of the distribution of fairy shrimp species in the my 1993 letter. I opined that none of the Wyoming habitats I had visited had only 1 species of fairy shrimp and few of the species I had collected occurred in only 1 habitat. The apparent exceptions of the new lindahli-like species restricted to rock pools and the new paludosa-like species restricted to sagebrush steppe ponds could be due to non-representative sampling. Branchinecta mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi) might genuinely be restricted to clay-rich waters but the water in “Coyote Lake” isn’t always opaque.

DB was very busy in 1993 and 1994, presenting papers at scientific meetings, teaching fairy shrimp identification classes in California, and collecting in New Mexico and probably elsewhere. He sent me his identifications of the 1993 samples in a March 14, 1995 letter. Sure enough, DB sent a photocopy of a previous report of Artemia males clasping other species but it lacked an explanation. He gave a pass to my species identification cheat-sheet. DB mentioned that he had found fairy shrimp like the streptocephalid in Horne’s Pond XII in southern Texas and co-authored a paper on a description of the new species that was due to be published in the near future. So that mystery was solved in spite of the lack of cooperation from Horne’s Pond XII. In addition, DB identified the tadpole shrimp from the “Lewiston Lakes” as Lepidurus lemmoni and the clam shrimp from the “Lewiston Lakes” and “Coyote Lake” as Caenestheriella belfragei (now Cyzicus belfragei).

I was not able to search for more fairy shrimp in 1994 so the delayed response by DB for the 1993 samples was no problem.

With Help from Denton Belk – top

I managed 1 trip to Wyoming in 1995. The late June date was not ideal but it turned out well. I found fairy shrimp in 5 previously visited ponds and collected samples from 3. Bull Canyon Pond had water for a change and both Branchinecta coloradensis and the paludosa-like species (identified visually) so I collected a sample there. Horne’s Pond XII had water and fairy shrimp at long last. The fairy shrimp appeared to be a branchinectid based on visual characters rather than a streptocephalid so I didn’t collect a sample.

I drove out to “Lost Creek Lake” and was overcome by what I saw. It was huge. The clay-colored water was kilometers across. Was this the day? With waders on my feet and net in hand, I ventured forth. I found lots of fairy shrimp, at least up to about 2 cm long (0.8″). Clam shrimp were also common. There were ostracods and cladocerans and an occasional tadpole shrimp. Finally I nabbed one, a monster fairy shrimp at least 5 cm (2″) long. The first one was a female. I needed a male for species identification. I kept searching, and searching. The big fairy shrimp were very rare. I probably should have changed my plans and spent the rest of the day there but I didn’t. I gave up. I ended up with only 3 of the big fairy shrimp, all females. To make matters worse, I hadn’t brought any alcohol to preserve them. I emptied out 2 1-gallon milk jugs with drinking water, filled them with lake water, and dropped the 3 big fairy shrimp and several of the smaller ones in. When I got home late the next day, 2 of the big fairy shrimp had died. 1 had disintegrated without a trace and 1 was mush. I put the live 1 and the corpse in alcohol to send to DB. Maybe the size alone would be enough to identify them.

After “Lost Creek Lake”, I sped out to “Brannan Reservoir”. I had previously collected Branchinecta gigas’s food, Branchinecta mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi), there. Maybe I would have better luck netting B. gigas in “Brannan Reservoir”. I didn’t. I found only small fairy shrimp, which I didn’t bother to sample.

I mailed the 2 samples I had collected, 1 from “Lost Creek Lake” and 1 from Bull Canyon Pond, to DB on July 1, 1995. That was all for 1995. In his July 11, 1995 reply, DB confirmed B. coloradensis and the paludosa-like species in Bull Canyon Pond and B. gigas and B. mackini (DB later changed the identification to B. readingi) in “Lost Creek Lake”. He would be leaving shortly for California to teach more fairy shrimp identification classes.

“Lost Creek Lake” with plenty of water, at last.

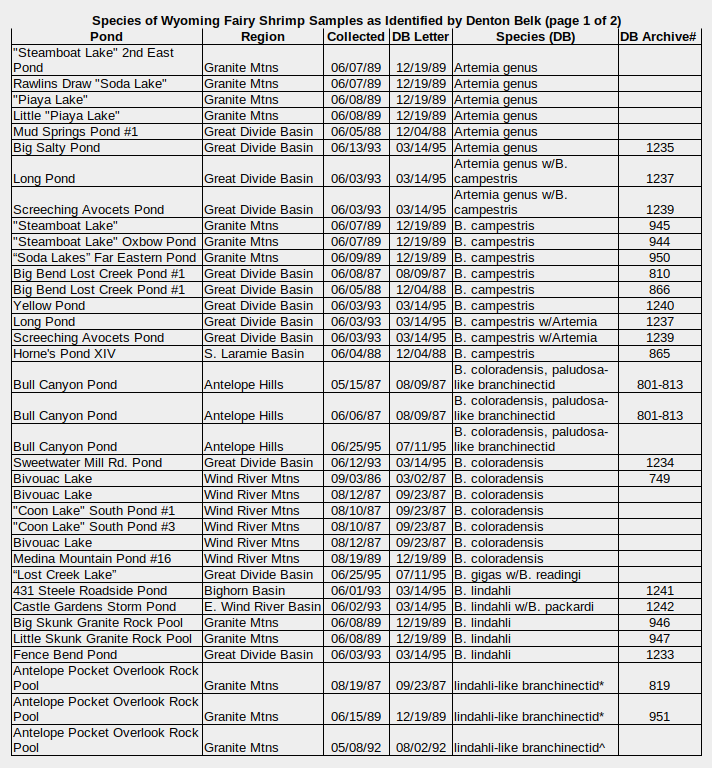

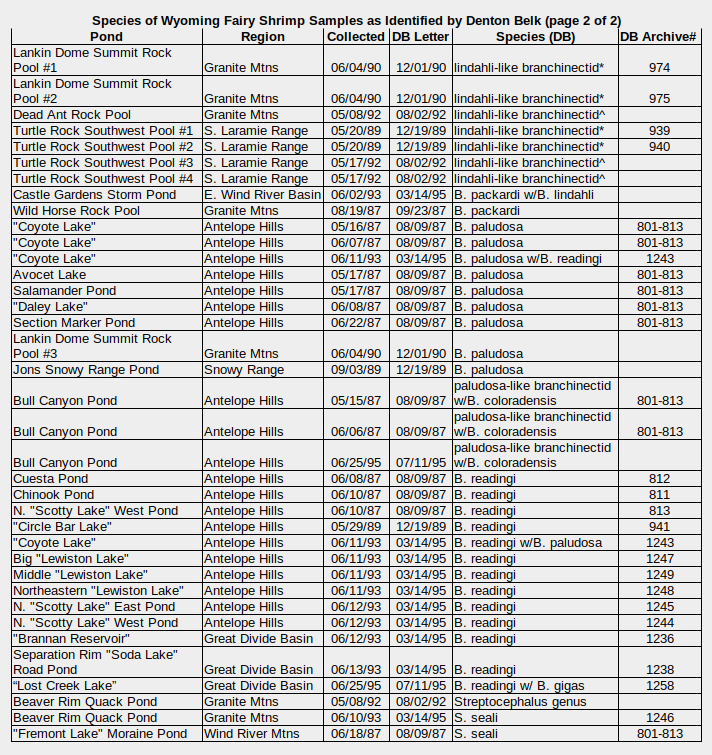

By July 1995, I had collected 64 fairy shrimp samples. DB’s species identifications are shown in the tables below. In all, the specimens included 11 species of fairy shrimp. Streptocephalus seali and Branchinecta gigas had not previously been reported in Wyoming. After DB’s death, the paludosa-like branchinectid was named and described as Branchinecta serrata and the lindahli-like branchinectid as Branchinecta constricta by Rogers (2006). In addition, Rogers (2006) determined that all the specimens DB had identified as Branchinecta campestris were Branchinecta lateralis, which he named and described. DB’s wife, Mary, had deposited DB’s extensive collection at the National Museum of Natural History (Rogers, 2006), where they are available to other researchers.

My searches covered a broad swath across central Wyoming from the northern Wind River Mountains in the northwest to the southern Laramie Range in the southeast and a few outliers. They are not representative of Wyoming but reflect my outdoor interests. They nonetheless include both ephemeral and semi-permanent water bodies and several environments.

- Alpine: Bighorn Mountains, Snowy Range, Wind River Mountains

- Sagebrush Steppe: Antelope Hills, Granite Mountains

- Short Grass Prairie: Southern Laramie Basin

- Rock Pool: Granite Mountains, Southern Laramie Range

- Sand Dunes: Killpecker Dune Field, Seminoe Dune Field

- Desert: Bighorn Basin, Eastern Wind River Basin, Great Divide Basin

Bivouac Lake, “Steamboat Lake”, and “Brannan Reservoir” may be the only permanent water bodies that I was able to find fairy shrimp in. Topographic maps suggest the Green River Basin and eastern Wyoming don’t have many ponds and eastern Wyoming is mostly private land anyway. I didn’t search woodland ponds on the Yellowstone plateau or coal-bed methane ponds in the Powder River Basin. I didn’t check out alpine lakes and ponds in the southern Beartooth Mountains, the Absaroka Mountains, the Tetons, or the Sierra Madre. There are certainly more fairy shrimp discoveries to be made in Wyoming and worldwide.

B. – genus Branchinecta; S. – genus Streptocephalus

* In an August 13, 1991 letter, DB hypothesized that the specimens are an unrecognized species rather his original identification as B. lindahli. He confirmed this in an August 2, 1992 letter.

^ In an August 2, 1992 letter, DB stated that the specimens are an unrecognized species.

1. The lindahli-like branchinectid was later named Branchinecta constricta by Rogers (2006).

2. The paludosa-like branchinectid was later named Branchinecta serrata by Rogers (2006).

3. The species identified as B. campestris by DB was later determined to be a new species by Rogers (2006), which he named Branchinecta lateralis.

If my samples averaged 12 specimens each (EIGWUU), that means I killed 768 fairy shrimp, not including any I killed inadvertently while netting or splashing through ponds. Was the information gained worth it?

Recently, species-specific qPCR assays of environmental DNA in pond water samples have been developed to monitor fairy shrimp of “conservation concern” in California. Such assays obviate the need to collect and kill fairy shrimp for species identification. Perfect agreement with dip-net surveys was achieved in 56 sampling events for 1 species but 13 sampling events for another species gave poor results with 38% of assay detections as false positives and 60% of non-detections as false negatives (Kieran and others, 2021). For the 3 ponds that produced the false positives, the target species was found on a later sampling event. In ponds with very young fairy shrimp, environmental DNA assays could yield more reliable results than net surveys due to the difficulties of seeing, netting, and identifying immature fairy shrimp. Development of qPCR assays is probably costly and the costs of such assays could be expensive if developed commercially.

Recently, species-specific qPCR assays of environmental DNA in pond water samples have been developed to monitor fairy shrimp of “conservation concern” in California. Such assays obviate the need to collect and kill fairy shrimp for species identification. Perfect agreement with dip-net surveys was achieved in 56 sampling events for 1 species but 13 sampling events for another species gave poor results with 38% of assay detections as false positives and 60% of non-detections as false negatives (Kieran and others, 2021). For the 3 ponds that produced the false positives, the target species was found on a later sampling event. In ponds with very young fairy shrimp, environmental DNA assays could yield more reliable results than net surveys due to the difficulties of seeing, netting, and identifying immature fairy shrimp. qPCR assays is no doubt more costly than using a net and a microscope.

It is also now possible to conduct genetic analyses of very small samples. Rogers and Aguilar (2020) were able to conduct detailed genetic analyses of single fairy shrimp specimens. Moorad and others (1997) described a method to analyze individual eggs. Analyzing eggs has the advantage of not depending on environmental factors for a hatch and could identify different species that might not hatch at the same time. I would never have guessed “Coyote Lake” would have Branchinecta mackini (renamed B. readingi) in addition to Branchinecta paludosa until DB identified them. With egg analyses, I could have found Branchinecta gigas in “Lost Creek Lake” in 1 trip rather than 4. Moorad and others (1997) didn’t discuss costs.

During my off-and-on fairy shrimp adventure from 1985 to 1995, I had learned a lot about fairy shrimp with the help of Denton Belk and for that I will always be grateful. He, is what a man of science should be. They, are amazing animals.

Since 1995, I haven’t collected any fairy shrimp samples. I nonetheless continued searching for fairy shrimp off and on in Wyoming through 2010 and in Nevada after 2012.