The poor quality of drain water reaching “Carson Lake” is not likely to change in the foreseeable future because flood irrigation of alfalfa on the Newlands Project is not likely to change in the foreseeable future. Switching to sprinkler or drip irrigation would not be politically acceptable. Drain water treatment would not be affordable. That leaves dilution.

The 1990 Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Rights Settlement Act in Public Law 100-618 was written with dilution in mind. Section 206(a) authorized the Department of Interior to purchase water rights to maintain 101 square km (25,000 acres) of wetlands on Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, “Carson Lake and Pasture”, and tribal lands, which will be referred to collectively as Lahontan Valley wetlands hereafter. Section 206(f) then established the “Lahontan Valley and Pyramid Lake Fish and Wildlife Fund” to hold money for the acquisitions and allow contributions from non-federal entities. In addition, the Navy was required to phase out irrigation at Fallon Naval Air Station and stabilize the lands with “high-desert plant species”(Section 206(c)). The water saved was to be used for the “Pyramid Lake” fishery and Lahontan Valley wetlands by the Department of Interior. Exercising the acquired water rights would result in deliveries of “Lahontan Reservoir” water directly to “Carson Lake and Pasture” and Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge wetlands and consequently dilute the drain waters also entering the wetlands.

101 square km (25,000 acres) is close to the estimate of the average area of wetlands during the period 1967-1986, which was later published by Kerley and others (1993, p. 19). It is about one-third of the estimated area of wetlands before 1845 (Kerley and others, 1993, p. 12). It is about one-fourth of the combined area of “Carson Lake and Pasture” under state ownership (93 square km, 23,000 acres) and of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge (314 square km, 77,520 acres) (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 1-14; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2008). It is also half the size of the irrigated area of the Newlands Project, which has been in the range of 166-239 square km (41,000-59,000 acres) annually since the 1980s (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 2013, p. 3-56). Back of the envelope, if wetlands use the same amount of water as irrigated crops, the federal and Nevada state governments would need to purchase rights to about half the water used in the Newlands project. Congress conjured up a fantasy.

Authorization of the purchase of water enables dilution but the details of implementation determine the ecosystem consequences. The first big question is how much water do the wetlands need to sustain ecosystems with lots of birds? The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that each 0.4 hectare (1 acre) of wetlands needs 6.17 million liters (5 acre-feet, 1.63 million gallons) of water (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 1-5), or 15.2 million liters per hectare. It and NDOW would need 154.2 billion liters (125,000 acre-feet, 40.7 billion gallons) per year to sustain “wetted playa wetlands, wet meadows, emergent marsh, and open water habitat” for 101 square km (25,000 acres) of “Great Basin wetlands ecosystem”.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

Congress appropriated $10.5 million for acquisition of water rights (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 1-34). In 1990, Nevada voters approved a $5 million bond to buy water rights for “Carson Lake and Pasture”. That supplemented $4 million previously authorized by the Nevada legislature that could be used for the same purpose if certain conditions were met (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 1-34 and 6-153). In its comment on the Final Environmental Impact Statement for water rights acquisition, the Nevada Division of State Lands stated that it had already spent $2,982,295 for 8.57 billion liters (6,951 acre-feet, 2.26 billion gallons) of water rights. At that rate, $9 million could purchase water rights for about 26 billion liters (21,000 acre-feet, 6.8 billion gallons) per year (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 6-153). That’s enough for 17 square km (4,200 acres) of wetlands, which is about 40% of the 40.5 square km (10,000 acres) of “Carson Lake” wetlands estimated by Kerley and others (1993, p. 19) for the 1967-1986 average.

Not all of the 154.2 billion liters (125,000 acre-feet, 40.7 billion gallons) per year needed to support Public Law 101-618’s aspirational goal of 101 square km (25,000 acres) of wetlands has to be purchased. The wetlands continue to receive Newlands drain water. In addition, the wetlands benefit from precautionary releases from “Lahontan Reservoir” during high-water years. Such releases are not diverted for irrigation and are termed “spills”. Delivering water to the wetlands rather than using it for flood irrigation changes drain and, to a lesser extent, spill flows. To estimate how much water needs to be purchased, one needs to estimate drain and spill flows.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service used a hydrologic model to estimate the amounts of drain inflows and spill inflows for the 5 alternative water right acquisition plans it proposed in 1996. Alternative 4 had the largest water rights purchases and no drain or spill inflows to the wetlands. Alternative 1 assumed only 24.7 billion liters (20,000 acre-feet, 6.52 billion gallons) would be purchased and had estimated drain and spill inflows of 37.0 billion liters (30,000 acre-feet, 9.78 billion gallons) and 10.6 billion liters (8,600 acre-feet, 2.80 billion gallons), respectively. For preferred Alternative 5, the model estimated 24.3 billion liters (19,700 acre-feet, 6.42 billion gallons) of drain inflow and 12.0 billion liters (9,700 acre-feet, 3.16 billion gallons) of spill inflow. That leaves 118 billion liters (95,600 acre-feet, 31.2 billion gallons) to be purchased (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 2-22, 2-28, 2-34 to 2-35).

Due to judicial rulings, not all of the purchased water can be used at the wetlands. Because users of water from the Carson and Truckee rivers want more water than is available and because different types of land need different amounts of water to achieve their various purposes, the Alpine Decree specified the maximum amounts of water that could be used for crop irrigation on bench and bottom lands and for wetlands of the Newlands Project even if the irrigator previously had water rights for more. The great majority of irrigated lands in the Newlands Project are bottom lands. These lands are allowed up to 10.7 million liters of water per hectare (3.5 acre-feet, 1.14 million gallons, per acre). Bench lands get 13.7 million liters per hectare (4.5 acre-feet, 1.47 million gallons, per acre). Wetlands get only 9.11 million liters per hectare (2.99 acre-feet, 0.97 million gallons, per acre). The latter figure is the judicially determined annual consumptive use of Carson River irrigation water, or the amount of water presumed to be taken up by crops, no matter what the crops are. The higher water duties for bottom and bench lands take conveyance losses into account. The amount of water needed for the wetlands must be multiplied by 1.17 (3.5 acre-feet / 2.99 acre-feet) to determine the amount of bottom land water rights that must be acquired in order for the desired amount of water to be delivered to the wetlands.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agreed to use the 1.17 conversion factor, or the one for bench lands as appropriate, in order to avoid having NDOW protest its requests to the State Engineer to transfer the water rights to the wetlands (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 2-21). The same principle was formalized for the transfer of “Carson Lake and Pasture” from the federal government to Nevada.

- “Conveyance of Carson Lake and Pasture to the State is subject to the following restrictive covenant. Any water right transferred by the State for use on Carson Lake and Pasture shall be limited to no more than 2.99 acre-feet per acre, except as further provided in this paragraph . . .” (Attachment A: Agreement for the transfer and management of Carson Lake and Pasture, in U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 2009).

Applying the conversion factor to the 118 billion liters (95,600 acre-feet, 31.2 billion gallons) of needed water, the amount of bottom land water rights that must be acquired to maintain 101 square km (25,000 acres) of Lahontan Valley wetlands is 138 billion liters (111,850 acre-feet, 36.4 billion gallons).

Thus, to sustain 101 square km (25,000 acres) of wetlands, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Nevada must purchase bottom-land water rights for 138 billion liters (111,850 acre-feet, 36.4 billion gallons) in order for 118 billion liters (95,600 acre-feet, 31.2 billion gallons) to be delivered to the wetlands so that the wetlands will receive 154.2 billion liters (125,000 acre-feet, 40.7 billion gallons) in combination with 36.3 billion liters (29,400 acre-feet, 9.6 billion gallons) of estimated drain and spill flows. This may not be legal. According to the Alpine Decree, only 92.2 billion liters (74,750 acre-feet, 24.4 billion gallons) of water can be applied to the desired area of wetlands, not 118 billion liters (95,600 acre-feet, 31.2 billion gallons). The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s estimated need of 118 billion liters (total need minus drain and spill inflows) results in an application rate of 11.6 million liters per hectare (3.82 acre-feet, 1.25 million gallons, per acre). This is higher than the permissible rate of 9.11 million liters per hectare (2.99 acre-feet, 0.97 million gallons, per acre).

Are there other sources of water? Probably not. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s (1996) water-rights acquisition Alternative 5 included several options that it thought were feasible. Discussions in the text demonstrated they were not although the Service did not admit that. For the transfer of water rights from the Middle Carson River basin, it was noted that inter-basin transfers involve the loss of the priority date of the water right so the transferred right has a current year priority date (p. 2-31). In over-appropriated Nevada, such a junior water right would only be usable in wet years, which may be few and far-between. Moreover, there is strong local opposition to inter-basin transfers in Nevada based on us versus them framing. This has stymied Southern Nevada Water Authority’s (Las Vegas’s) attempts to acquire water in distant basins in order to compensate for diminishing Colorado River flows.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

Effluent from the City of Fallon’s and Fallon Naval Air Station’s water treatment facilities would not be subject to the Alpine Decree. The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District (2010, Table 8, p. 4-4) has received an annual average of 1.4 billion liters (1,131 acre-feet, 0.37 billion gallons) of Fallon effluent. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1996, p. 2-33) thought that this source could provide up to 3.7 billion liters (3,000 acre-feet, 0.98 billion gallons) at some point in the future due to population growth. The effluent is discharged into Newlands drains and the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District considers it part of the Newlands supply. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or Nevada Division of State Lands would have to make a deal with Fallon and the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District to get the water delivered to the wetlands. There would likely be local opposition to such a deal. In any case, this is a drop in the bucket. Maybe a deal to take Carson City effluent from Carson River or Reno-Sparks effluent from the Truckee would make a difference. “Lake Tahoe” effluent is mentioned in the Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Water Rights Settlement Act and “Lake Tahoe” and Truckee Meadows (Reno-Sparks) effluents are mentioned in the Truckee River Operating Agreement so use of effluent from the Carson or Truckee rivers may come with legal entanglements.

There is moderately good water below the Carson Desert but using it for wetlands would be difficult. The City of Fallon and Fallon Naval Air Station obtain water from a confined, fractured, basalt aquifer northeast of Fallon. A few analyses indicate TDS of about 500 mg/L, less than 100 mg/L sulfate, up to 0.14 mg/L arsenic (treatment required for drinking water), up to 2.1 mg/L boron, about 0.001 mg/L selenium, and up to 0.0036 mg/L uranium (Glancy, 1986, Table 5, p. 22-23). Fallon No. 1 and No. 3 wells can yield about 3,785 liters (1,000 gallons) per minute for about 20 hours (Glancy, 1986, Table 3, p. 18) from a water-bearing zone 122-152 m (400-500 feet) deep with depth to water of less than 18 m (60 feet) (Glancy, 1986, Tables 3 and 4, p. 18, and Table 1, p. 8). The basalt intrusion is no more than 13 km (8 miles) long and 7 km (4 miles) wide (Glancy, 1986, Figure 5, p. 16-17). Any attempt to construct high-yield wells in it for wetland supply would likely ignite a firestorm.

Reasonably good quality water in Lake Lahontan sediments below the depths influenced by evaporation of Newlands water has been found but areal and volumetric extents are poorly known and yields may be generally low. For example, well bcb1 in Township 19 North, Range 27 West, Section 19, had 58 mg/L sulfate, 0.012 mg/L arsenic (treatment required for drinking water), 0.45 mg/L boron, 0.013 mg/L lithium, 0.03 mg/L molybdenum, less than 0.001 mg/L selenium, and 0.001 mg/L uranium (analysis #65 in Whitney, 1994). TDS was not measured but the sum of the major ions was 417 mg/L. The well is 30.2 m (99 feet) deep. Unfortunately, this location is west of Fallon and a long way from “Carson Lake” and Stillwater Marsh. Relatively deep drilling for good water in the vicinity of “Carson Lake” or Stillwater Marsh has not been done because these were federal lands where nobody lives.

Using ground water would be costly. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1996, p. 2-34) estimated that 9 wells yielding 3,785 liters (1,000 gallons) per minute each would cost up to $700,000 to drill and complete and up to $500,000 per year to operate. Such wells could be used to supply 8.39-17.6 billion liters (6,800-14,300 acre-feet, 2.22-4.66 billion gallons) per year (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 2-35). In theory, the supply could be increased with more wells at greater cost to make up the difference between the 118 billion liters needed and the 92 billion liters of water right transfers allowable under the Alpine Decree.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (1996, p. 2-33) regarded groundwater as the least likely option in Alternative 5 to succeed “due to two key issues”. One is the expected poor water quality in the vicinity of “Carson Lake and Pasture” and of Stillwater Marsh. This is reasonable given the nature of Lake Lahontan sediments but it is actually an open question. Drilling has been insufficient to test the water quality in these areas. Drilling has also been insufficient to estimate likely yields. Glancy (1986, p. 54) found only 15 driller’s logs with specific capacity data for the “intermediate alluvial aquifer” (defined as deeper than 15.2 m, 50′). The highest specific capacity was only 3% of that for the high-yielding Fallon No. 1, (Glancy, 1986, Table 3, p. 18).

The second issue is the deal killer. The Lahontan Valley is closed to new ground water appropriations (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 2-33). The State Engineer’s Order 1116 of August 22, 1995 for the Carson Desert Basin stated:

- “. . . it is ordered that, with the following exceptions, applications filed to appropriate water from the groundwater source pursuant to NRS 534.120 within the designated Carson Desert Ground Water Basin will be denied” (http://water.nv.gov/StateEnginersOrdersList.aspx, select Basin number 101).

The exceptions include wells producing less than 15,100 liters (4,000 gallons) per day and geothermal wells.

The geothermal aquifer is an intriguing possibility for Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, which overlaps the Stillwater geothermal resource (Morgan, 1982). Although median TDS of 13 analyses is 4,100 mg/L, sulfate is only 170 mg/L and the trace element concentrations are not too bad. Median concentrations in mg/L are 0.006 for arsenic (below aquatic life standard of 0.15 mg/L and drinking water standard of 0.01 mg/L), 16 mg/L for boron (above Eisler’s, 1990, aquatic life criteria of 10 mg/L for sensitive aquatic animals), 2.0 mg/L for lithium, and 0.006 mg/L for selenium (above Nevada’s aquatic life standard of 0.0019 mg/L). 9 of 9 analyses were below the detection limit of 0.0002 mg/L for mercury (below the aquatic life standard of 0.00077 mg/L and the drinking water standard of 0.002 mg/L). 8 of 9 analyses were below the detection limit of 0.02 mg/L for copper and 7 of 9 analyses were below the detection limit of 0.05 mg/L for zinc (9 analyses from Fosbury and others, 2008; 4 analyses from Morgan, 1982). Molybdenum and uranium concentrations were not determined. High-TDS is not a problem for birds, as demonstrated by “Great Salt Lake” and “Mono Lake”, but a brackish ecosystem would be a significant departure from the pre-settlement ecosystem. If boron and selenium are not the killers in the Carson Desert wetlands, then use of geothermal water might be okay.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

In principle, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Nevada Division of State Lands could buy existing ground water rights and either figure out how to convey the pumped water to the wetlands or transfer the rights to a newly constructed well adjacent to the wetlands. If there are not willing sellers with high-yield wells, it could take hundreds of domestic and stock well water rights to add up to a few wetland water supply wells. Using Newlands drains as a conveyance would subject the pumped water to degradation by the poorer quality shallow ground water seeping into the drains and construction of pipelines or canals or trucking the water are probably cost-prohibitive. Transferring the use and place of use of a purchased ground water right would likely face local opposition even if the State Engineer determined that the transfer would not harm existing ground water users.

At the end of the day, the Alpine Decree may make the water acquisition authority of Public Law 101-618 moot. Regardless of the area stated in the law and regardless of the amount of water rights purchased, the Alpine Decree limits the use of the purchased Newlands water rights to less than what U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service thinks is needed to sustain Great Basin wetlands.

The water volumes mentioned above for delivery to Lahontan Valley wetlands do not include evaporation and canal seepage losses. In 2009, “water available” to the Newlands farmers was 74% of the water supply after accounting for seepage, evaporation, and spills (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2010, Table 6, p. 2-8). Excluding evaporation and seepage losses from “Lahontan Reservoir” (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2010, Table 4, p. 2-5) raises the available water volume to 80% of the below-Lahontan Dam supply. For 118 billion liters (95,600 acre-feet, 31.2 billion gallons) to reach the wetlands, about 148 billion liters (119,500 acre-feet, 39.0 billion gallons) would have to be released from “Lahontan Reservoir” annually. That is about a third of the average annual “Lahontan Reservoir” outflow of 475 billion liters (385,000 acre-feet, 125 billion gallons) for the years 1966-1991 (Maurer and others, 1993, p. 15).

Using Nevada’s pre-1996 acquisition cost of $348,000/billion liters ($2,982,295 / 8.57 billion liters), $19.5 million gets NDOW and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 56.0 billion liters (45,435 acre-feet, 14.8 billion gallons) of water rights. That’s less than half the aspirational goal for 138 billion liters (111,850 acre-feet, 36.4 billion gallons) of purchased water rights.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

The purchase of water rights to serve Lahontan Valley wetlands has proved to be contentious. For example, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the use of Newlands irrigation water at “Carson Lake and Pasture” in 2013. The court said that Newlands water rights can only be used for irrigation and that NDOW using the water to grow duck food at “Carson Lake and Pasture” is not irrigation

(www.nevadaappeal.com/news/2013/jul/30/9th-circuit-court-rejects-using-water-for-waterfow/). Accordingly, the State Engineer should not have allowed the transfer of the purchased water rights. The Nevada Appeal article hinted at who was mad by adding that the court also found that the “Pyramid Lake” Paiute tribe has standing to oppose the transfer because use of water from “Lahontan Reservoir” at “Carson Lake and Pasture” could increase demand for Truckee River water by farmers of the Newlands Project. The “Pyramid Lake” tribe has a strong interest in protecting its lake and the fish in it. This ruling effectively squelched the wetlands aspiration of Public Law 101-618. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and maybe Nevada Division of State Lands have apparently continued to purchase water rights for the wetlands so there may have been other rulings that allowed the State Engineer to transfer the use of the irrigation water rights.

Another bone of contention has been expansion of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge. The 2003 notice for the availability of the Record of Decision for a boundary revision (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2003) identified the preferred alternative as one that would eliminate the Stillwater Wildlife Management Area and transfer much of its area into the refuge for a total of 697 square km (172,254 acres). That didn’t happen as the 2008 brochure for Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge says its area is 314 square km (77,500 acres) and this is what is currently shown on The National Map. This area is the same as before the boundary change plans. The Federal Register notice noted that the Nevada Board of Wildlife Commissioners unanimously supported the chosen alternative but Churchill County opposed it (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 2003, p. 18,257). Federal agencies usually test the political winds before issuing decisions but Congress disregarded this one. Legislation to change the refuge boundary did not pass but Stillwater Wildlife Management Area disappeared anyway.

The above 2 articles suggest that there is powerful local opposition to the expansion and conservation of Lahontan Valley wetlands.

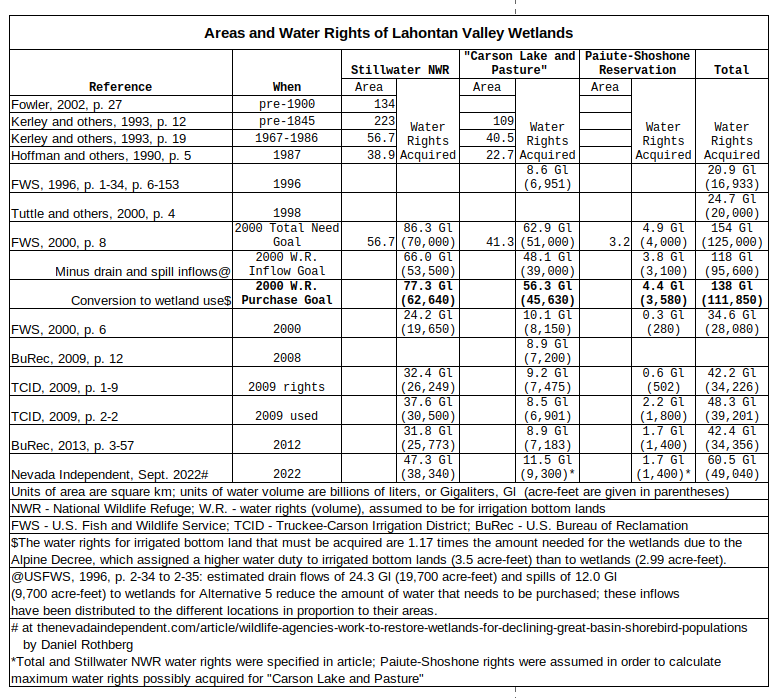

Fortuitously, a 2022 article in the Nevada Independent provided a snapshot of how things recently stood with the acquisition of water rights. According to the article, a total of 60.5 billion liters (49,040 acre-feet) have been purchased by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Nevada Division of State Lands and 47.3 billion liters (38,040 acre-feet) of that are for Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge (thenevadaindependent.com/article/wildlife-agencies-work-to-restore-wetlands-for-declining-great-basin-shorebird-populations). As summarized in the table of Areas and Water Rights of Lahontan Valley Wetlands, the total is less than half of what would be needed to support the aspirational goal for 101 square km (25,000 acres) of wetlands. There are inconsistencies in the estimates of acquired water rights by different sources at different times in the table but a substantial shortfall is clear.

In the case of “Carson Lake and Pasture”, the maximum amount of water rights that can be inferred from the numbers in the Nevada Independent article, 11.5 billion liters, is not even half of the 26 billion liters (21,000 acre-feet, 6.8 billion gallons) that the Nevada Division of State Lands said that it could possibly afford in 1996 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1996, p. 6-153). It is about 20% of the amount needed to support the 41.3 square km (10,200 acres) of wetlands hoped for at “Carson Lake and Pasture”. In the 2009 transfer environmental assessment, the Bureau of Reclamation stated that NDOW “is expected to acquire 12,800-23,000 acre-feet [15.8-28.4 billion liters] from drains, the Carson Division, and upstream of Lahontan Reservoir” (U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, 2009, p. 12). It doesn’t look like Nevada acquisitions will reach the bottom of that range. If Nevada has indeed acquired 11.5 billion liters (9,300 acre-feet) of water rights, that would be enough for 9.5 square km (2,355 acres) of wetlands, assuming a water need of 15.2 million liters per hectare (5 acre-feet per acre) and with drain and spill inflows scaled down from aspirational to 2022 water rights purchases and divided proportionally between “Carson Lake and Pasture”, Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, and Paiute-Shoshone wetlands.

For context, 11.5 billion liters (9,300 acre-feet, 3.03 billion gallons) of water is enough to supply the annual residential indoor water needs of approximately 163,750 people. To arrive at this figure, I used 192 liters/day (50.7 gallons/day) based on the “Correlation-Based 2017-2019 Tract Level” average calculated with the “Rainfall Adjustment Method” by the California Department of Water Resources (2021, p. 44). California Department of Water Resources has put more effort into accurately estimating water use than most others. How long before the populations in Reno-Sparks, Carson City, Fernley, the “Lake Tahoe” basin, and Fallon add that many people? Where will they get their water from?

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

Purchases of water rights are one-time events. Using the water entails annual expenditures. NDOW pays the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District for the water it uses at “Carson Lake and Pasture” every year. Because the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District charges by the acre rather than by the acre-foot, taking the maximum allowed water for 9.5 square km (2,355 acres) would cost about $105,740 at 2009 rates of $44.90/acre ($110.95/hectare) (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2009, p. 1-11). The migratory bird stamp fee of $25 (NDOW, 2022, Small Game Hunting Regulations and Seasons) would cover that if there are at least 4,300 duck and geese hunters annually.

Whether or not NDOW and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reach their water purchase goals, day-to-day and year-to-year water management practices can mitigate the effects of poor quality drain water. 2 extreme choices would be to maximize bird habitat or to maximize ecosystem health. In the first case, dikes and dams would be used to retain all received drain and purchased water as long as possible. This would lead to greater evapotranspiration and poorer water quality but more bird habitat and more birds. In the latter case, drain water would be directed to flow through the ponds or, if possible, diverted into other drains, and predominantly purchased water would be retained only as long as water quality met certain benchmarks. This would lead to smaller wetland areas, less bird food, and fewer birds but better water quality, healthier plants and animals, and maybe more species.

Traditional wetland management at Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge has been “to provide maximum production of aquatic and emergent vegetation for food and nesting habitat for migratory birds” (Tuttle and others, 1996, p. 4). NDOW may be under even greater pressure than U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to maximize bird populations due to the importance of duck hunting at “Carson Lake and Pasture”.

Examples of ecosystem degradation that could continue with an emphasis on bird production were summarized by Tuttle and others (2002, p. 55):

- “In general, the dominant wetland plants currently found in Lahontan Valley are tolerant of saline conditions, whereas some of the historically described saline-intolerant communities are no longer found (Bundy and others, 1996).”

- “Aquatic-invertebrate communities in Lahontan Valley wetlands, particularly in Lead Lake and Sprig Pond, exhibited some characteristics consistent with impaired stream systems, including absence of sensitive taxa, dominance of tolerant taxa, and low taxa richness.”

- “Although at least 5 native and 15 introduced fishes have access to Lahontan Valley wetlands, only 1 native and 4 nonnative fish species were found in the wetlands.”

The alternative is to deliver purchased water to small, selected wetland areas and to flush through or reroute most drain waters around them. Rather than evaporating from the ponds and marshes and further degrading the surface and ground waters, the drain waters would quickly reach the Sump at “Carson Lake and Pasture” or the Carson Sink playa north of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge and do most of their evaporating there. The refuge has 16 main marsh units and a “system of water delivery canals, dikes, and levees” (Tuttle and others, 1996, p. 4) that would make such management relatively easy at Stillwater Marsh. “Carson Lake and Pasture” may not. It might be possible to route drain water from “Carson Lake and Pasture” into the Diagonal Drain – if not by gravity then by pumping – and send it to the refuge where U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service could divert it to the Sink.

Ultimately, the best disposal site for the Newlands irrigation returns is the Fallon Range Training Complex’s B-20 bombing range, which now borders the north end of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge and covers essentially all of Carson Sink. The nasty water can do no harm there as the bombing range will never be used for geothermal plants, solar arrays, salt or lithium mines, water wells, alfalfa fields with center-pivot sprinklers, land sailing, off-highway vehicle recreation, star gazing, Paiute ceremonies, rural living, or anything else. The drain water would spread out on the playa and evaporate quickly. Vegetation would likely remain minimal, as on most Nevada playas. However in wet years, water might linger on the playa long enough for fairy shrimp to hatch – if they can tolerate the water quality.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

The key mitigations for producing healthier birds, though fewer in number, and healthier plants, invertebrates, and fish, are to maximize the ratio of purchased water to drain water, reduce pond sizes, and allow some wetland areas to dry up. Due to the flat topography, large ponds lose more water per unit volume to evaporation than smaller ponds as a result of larger area to volume ratios. At the same inflow rates, a small pond can be refreshed more quickly with less water than a large pond.

- “Measures to reduce water retention time in wetlands should be considered. One method of reducing hydrologic retention time is the reduction of impoundment sizes” (Tuttle and others, 1996, p. 61).

Minimizing use of drain water would likely lead to some ponds or marshes drying up but targeted desiccation could be beneficial on its own.

- “Desiccation of wetlands to volatilize mercury should be further evaluated. Because mercury contamination on Stillwater NWR appears to be confined to a few wetlands, permanent desiccation of mercury-contaminated wetlands should also be considered” (Tuttle and others, p. 61).

The shallow ground water that seeps into drains does not have high mercury concentrations. High mercury concentrations come from the dissolution of mercury in contaminated surficial sediments deposited by Carson River floods since 1860.

Other options for improving water quality in the wetlands, at least indirectly, have fallen by the way side. Section 209(c) of Public Law 101-618 required a study of the feasibility of improving the efficiency of the Newlands Project such that 75% of the water received in “Lahontan Reservoir” reached the headgate where it would be used. This could be done by lining canals to reduce seepage, which would reduce ground water recharge and consequent drain flow. The Truckee-Carson Irrigation District has reduced the use of Sheckler and other reservoirs to lessen evaporation and seepage (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2010, p. 1-4) and has reused drain water (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2010, p. 3-12) to improve project efficiency but in 2009, seepage was still 51.5 billion liters (41,775 acre-feet, 13.6 billion gallons), or 14% of the water supply (Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, 2010, Table 6, p. 2-8). A severe complication for seepage control is that hundreds, if not thousands, of shallow private water wells rely on seepage for much of their yields (Maurer and others, 1994, p. 2). Tellingly, the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District’s (2010) Water Conservation Plan does not state what the efficiency of the Newlands Project is, has been, or should be.

The political impossibility of suggesting that farmers switch from flood irrigation to sprinkler or drip systems is illustrated by Bureau of Reclamation’s forgiveness of project construction costs. The federal government considered 74% of Lahontan Basin construction costs “nonreimbursable” (i.e., $67,104,000 of $90,782,000), gave the irrigators “credits” of $4,578,000, and allocated “other repayments” of $2,045,000 toward construction costs (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2014, Tables 5 and 6, p. 37, 40). “Other repayments” might have included grazing fees or sales from the power plant at Lahontan Dam, which do not come from irrigators. As of 2012, irrigators had paid 5.7% ($4,946,000) of project construction costs other than power project costs ($87,337,000) and 24% of the reimbursable irrigation construction costs ($20,233,000). The federal government still expects to get $166,000 from the Lahontan Valley irrigators but repayment of $8,498,000 has been deferred (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2014, Table 6, p. 40), perhaps indefinitely. Irrigators do not pay interest on what they owe the federal government. The category “Lahontan Basin construction” includes unspecified projects in the area other than the Newlands Project, which may or may not have benefited Newlands irrigators.

A 1994 accounting for the Newlands Project separately indicated that the reimbursable cost for irrigators was $10,729,000 (these are early 1900s dollars) and that repayments of $4,135,000, or 38.5%, had been made (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 1996, Appendix IV, p. 48 and Appendix V, p. 58). The federal government wiped away 44.6% of the cost with a “charge-off” of $4,789,000 (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 1996, Appendix VI, p. 66). Such federal largesse is not unique to the Newlands Project. Irrigators on 41 of 133 projects reviewed in 1996 were charged less than 31% of their reimbursable costs due to financial assistance and charge-offs (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 1996, p. 30). Any mitigation measure that imposes a cost on irrigators is not likely to be proposed or accepted.

What NDOW and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service are doing or are planning to do to manage the water flows and the wetlands of the Carson Desert is not known by me. There is no relevant information on their web sites. I suspect that just as NDOW perpetuates the no-fish-meals-per-month “anglers paradise” of “Lahontan Reservoir”, it will perpetuate a toxic duck farm at “Carson Lake and Pasture”.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

Carson River waters that used to flow to “Carson Lake” via the South Branch, to Stillwater Marsh via Stillwater Slough and New River, or to Carson Sink at Pelican Island via Old River are now delivered to crop lands of the Newlands Project. The consequences have been far reaching.

To recap the problem at “Carson Lake and Pasture”:

-

- The U.S. government built Derby Dam, Truckee Canal, Lahontan Dam, and numerous canals for the Newlands Project in 1900-1920 in order to promote irrigated agriculture in the Lahontan Valley around Fallon (The Newlands Project). As a result, “Lahontan Reservoir” was able to release an average (1975-1992) of 456 billion liters (120.6 billion gallons, 370,000 acre-feet) to an average (1984-1990) of 225 square km (56,000 acres) of irrigated land. All the delivered water is used for flood irrigation and alfalfa is the predominant crop. The Newlands Project is managed by the Truckee-Carson Irrigation District, which collects fees for water use.

- Diversion of water from the Carson River for irrigation caused the wetlands of “Carson Lake” and Stillwater Marsh to dry. They might have withered away almost completely if not for an unforeseen consequence of Newlands irrigation practices. The water table rose so much that fields became waterlogged. To remedy the situation, the Bureau of Reclamation paid to construct drains (“Carson Lake and Pasture”). The drains ultimately ended in the regional low spots of the former “Carson Lake” and Stillwater Marsh. Wetlands were at least partially restored by the drain waters and attracted a lot of wading birds and ducks. The soggy area around the former “Carson Lake” became known as “Carson Lake and Pasture” because it was used for grazing as well as for feeding ducks. “Carson Lake and Pasture” was transferred from the federal government to the State of Nevada in 2021. As part the deal, Nevada pledged to maintain and enhance “shorebird” habitat, which would also be good for ducks.

- Although a high “Carson Lake” level could drain to Stillwater Marsh pre-Newlands, “Carson Lake and Pasture” is now a terminal wetland. The drain water which reaches the area has nowhere else to go (From “Carson Lake” to Newlands Sump). A minor, unquantified portion of the drain waters may sink into the ground but most of the water is used by plants or evaporates. The accumulation of precipitated solids over time could kill off the marsh and submergent vegetation. To avoid that, “Carson Lake and Pasture” has been diked so that water with very high TDS due to evaporation can be drained off to the Sump for final disappearance. All dissolved solutes remain after evaporation is completed. They include potentially harmful trace elements such as mercury and arsenic.

- Use of mercury for milling gold-silver ores of the Comstock district has resulted in contamination at mine and mill sites around Virginia City and above Dayton. Heavy precipitation and snowmelt has carried mercury from these sites into the Carson River and occasional flooding has delivered mercury to everywhere the river goes downstream of Dayton. The resulting Carson River Mercury Superfund Site covers a large area. Particulate mercury in flood sediments dissolves when covered by water. The dissolved mercury is taken up the food chain to fish and birds. Mercury concentrations in fish of “Lahontan Reservoir” are so high that it has been recommended by the Nevada Division of Behavioral and Public Health that people not eat any (according to NDOW’s fishing regulations). Ducks have had similarly high concentrations at times. A health advisory was issued in 1989. Although the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency helped post warning signs for eating fish, it does not now consider eating fish or duck from the Superfund Site a health risk for recreational users (How EPA Ducked the Mercury Risk of Ducks at “Carson Lake”).

- The Carson Desert is floored by sediments that were deposited as Lake Lahontan waxed and waned during recent glacial and interglacial periods. The sediments do not have unusually high concentrations of potentially harmful trace elements but the shaley character of the sediments means they do have higher concentrations than many rock types, like sandstone and granite (Sediments of Lake Lahontan). The trace elements can be mobilized into ground or surface water under the appropriate chemical conditions. The rise of the water table due to flood irrigation exposed previously unsaturated sediments to dissolution and desorption reactions.

- Evapotranspiration removes most of the irrigation water from the crop lands but some runs off into drains (Newlands Farm Run-off). The chemistry of this water is not known but concentrations of most solutes are increased by evapotranspiration. High flows in the drains during irrigation season are mostly farm run-off.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top

- Shallow ground water in the area of the Newlands Project has generally poor quality and, in some cases, very poor quality (Newlands Shallow Ground Water). This is the irrigation water that did not evaporate, transpire, or run-off but seeped below the ground surface and percolated to the water table. The primary cause of the poor water quality is evapotranspiration in reservoirs and canals, on farmers’ fields, in wetlands, and in the pore spaces of the sediments.

- Graphs of various solutes plotted against chloride in shallow ground water (Newlands Shallow Ground Water) indicate that some increase predominantly due to evaporation. Others deviate from this pattern. At chloride concentrations greater than about 200 mg/L, boron and molybdenum are controlled primarily by evaporation. Arsenic, uranium, lithium and selenium are removed by precipitation/adsorption. Patterns for calcium and sulfate indicate various degrees of calcite and gypsum precipitation. Magnesium deviations from the evaporation trend suggest dolomite precipitation but there is no mineralogical evidence for this. There is graphical evidence for the dissolution of halite above about 700 mg/L chloride on the graph of sodium versus chloride although the presence of halite in shallow soils and sediments has not been reported.

- The purpose of drains is to lower the water table (Newlands Drain Water). Over their lengths, drains accumulate ground waters and farm run-off with locally varying chemistry and carry them to terminal wetlands at “Carson Lake and Pasture” and Stillwater Marsh. Concentration profiles for drain waters demonstrate some of the same processes identified in shallow ground water, such as precipitation of calcite, dissolution of halite, and precipitation or adsorption of arsenic. Qualitatively, the chemistry of “Sprig Pond” at “Carson Lake” is very similar to that of “Carson Lake” Drain sampled above “Carson Lake” both in the winter and during irrigation season.

- Experiments by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists showed that some drain and lake waters are toxic to cladocerans and fish (Toxicity of Newlands Drain Water). A “Pintail Bay”-like solution was found to be more toxic than a seawater-like solution of the same TDS. When small concentrations of trace elements were added, death rates increased. In drain waters, high concentrations of TDS, boron, molybdenum, lithium, and selenium had strong correlations with high death rates of fathead minnows. For water collected from drains upstream of “Carson Lake” in March, boron, chromium, copper, uranium, and TDS had the highest correlations with cladoceran mortality while nickel, molybdenum, and lithium also had significant correlations. All these correlations flipped to insignificant and negative in August although cladoceran death rates remained high. Strong correlations between most solutes with TDS due to evaporation make it difficult to determine which solutes are responsible for the deaths.

- Comparison of trace element concentrations in drains and lakes with experimentally determined median lethal concentrations and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or Nevada aquatic life criteria suggests arsenic and boron are the trace elements most likely to cause harmful effects despite the lack of experimental evidence for consistently higher arsenic concentrations in more toxic waters. Arsenic and boron concentrations in plants, insects, fish, and birds exhibit the opposite of biomagnification (The Effects of Water Quality on Wildlife at “Carson Lake”). 21% of algae analyses had arsenic concentrations greater than the adverse effect level of 30 ppm (dry) for bird diets. Muscle and liver samples of birds shot at “Carson Lake” had a maximum arsenic concentration of only 1.05 ppm (dry). 14% of bird analyses had boron concentrations greater than the adverse effect level of 108 ppm (dry) but 72% of algae analyses did. All 27 algae analyses had boron concentrations greater the the bird diet adverse effect level of 30 ppm.

- Drain and lake waters have selenium concentrations below their respective aquatic life criteria but analyses of plants and animals indicate bioaccumulation by plants and biomagnification up the food chain to birds. Most surface water samples from “Carson Lake and Pasture” and upstream drains had selenium concentrations below the detection limit of 0.001 mg/L; the maximum was 0.002 mg/L. Median concentrations (dry weight basis) of selenium were 0.65 ppm for algae and pondweed, 1.10 ppm for insects, 1.95 ppm for fish, 1.10 ppm for duck muscle. 4.70 ppm for duck liver, and 8.70 ppm for avocet and black-necked stilt liver. 36% of stilt and avocet liver analyses exceeded the 10 ppm threshold for harmful effects.

- Bioaccumulation and biomagnification also occur with mercury. Most surface water samples had mercury concentrations below the detection limit of 0.0001 mg/L and the maximum was 0.0003 mg/L. 1 of 27 analyses of algae and pondweed and 5 of 10 insect analyses exceeded the 3 ppm adverse effect threshold for bird diets. Median concentrations (dry weight basis) of mercury were 2.70 ppm for duck muscle, 4.40 ppm for duck liver, and 5.70 ppm for avocet and stilt liver. 44% of duck muscle analyses had mercury greater than the 3.6 ppm (dry weight basis) maximum mercury concentration allowed in fish sold as food in the European Union.

- Poor water quality has not caused widespread deaths or deformities of fish or birds at “Carson Lake and Pasture” The Effects of Water Quality on Wildlife at “Carson Lake”). Sublethal effects, if any, have not been documented. Evidence of ecosystem degradation is widespread nonetheless. Plants that are not tolerant of high-TDS waters have decreased in abundance. Bottom-dwelling and swimming invertebrate communities have few species. Only a few species of forage fish have survived although “Carson Lake” had a thriving fishery before the Newlands Project. River otters, frogs, and turtles have been extirpated and clams have survived in only a few places.

- The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, as manager of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, and NDOW, as manager of “Carson Lake and Pasture”, have been committed to maintain and to partially restore Lahontan Valley wetland ecosystems by passage of Public Law 101-618 and by agreements between Nevada and the United States governing the transfer of “Carson Lake and Pasture” to Nevada (this page). The primary and perhaps only means the agencies have to mitigate the poor quality of Newlands drain waters is to dilute it with water from “Lahontan Reservoir” delivered directly to the wetlands. More than 30 years after passage of Public Law 100-618 in 1990, the agencies are still far short of the law’s authorization to support 101 square km (25,000 acres) of wetlands in Lahontan Valley. As of September 2022, only 60.5 billion liters (49,040 acre-feet) of the 138 billion liters (111,850 acre-feet) needed had been obtained. More troublesome, the Alpine Decree appears to prevent the agencies from using as much water as they think they need, biologically, per area of land.

Snow falls in the Sierra Nevada. Snowmelt flows into the Carson River. The Carson River flows down hill to “Carson Lake and Pasture”. Water dissolves soluble minerals and precipitates insoluble minerals. Water evaporates. Water quality deteriorates. Some species tolerate poor water quality; some don’t. It’s all predictable.

Mitigation of Poor Water Quality at “Carson Lake” – top