The Carson River Mercury Superfund Site is large. It has been divided into 2 parts. Operable Unit 1 includes mine and mill sites in the Virginia Range near Virginia City and Dayton. Operable Unit 2 includes the Carson River from east of Carson City past Dayton and Fort Churchill to “Lahontan Reservoir”; the reservoir; Newlands canals, drains, and reservoirs below “Lahontan Reservoir”; “Carson Lake” and surrounding wetlands; lakes, wetlands, and channels of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge; and even the Carson Sink northeast of Old River and Pelican Island (Aptim Federal Services, LLC, 2020, Figure 1-1, pdf page 213).

The mercury is from the milling of gold and silver ores of the Comstock Lode near Virginia City and nearby mines from 1860 to about 1880 (https://www.nps.gov/places/virginia-city-historic-district.htm). Mercury was used in the amalgamation process of refining the ores. Gold and silver dissolve in liquid mercury metal, which was mixed into finely ground ore. Due to its high density, the mercury amalgam was easily separated from the ground rock by gravity methods. On heating, the mercury vaporized, leaving the gold and silver. The mercury was recovered by condensation and used again. The process is simple and cheap but mercury can be lost by inefficient separation, spills, or escape of mercury vapor. It has been estimated that about 6.8 million kilograms (7,500 tons) of mercury were not recovered (Hoffman and Thomas, 2000, p.8).

Most of the mills were near Virginia City, which is about 80 km (48 miles) west of “Carson Lake”, in the foothills to the south, or along the Carson River near Dayton.

There was minimal effort to stabilize mill tailings or the soils around mine and mill sites and the Virginia Range has steep slopes. Snow melt or rain has at times washed the tailings into tributaries of the Carson River and floods have carried the fine tailings particles down the the South Branch to “Carson Lake”, down New River to Stillwater Marsh, or down Old River to Pelican Island, depending on the main channel at the time. Mercury tends to stick to organic and inorganic particles (Hoffman, 1994, p. 23) so it goes along for the ride. As an example of how this happened, the August 12, 1867 Gold Hill News reported that “[t]he storm of yesterday afternoon washed away Carpenter and Birdsall’s Dam, at Dayton, and the Ophir Mill Dam, and did the same job for the Kelsey Mill. A large number of tailing sluices, in the canon, from Devil’s Gate to Dayton, were washed out . . .” (McQuivey, 2005, p. 9). The earlier spring flood in 1867 had created New River so this summer flood might be a cause of the high mercury concentrations in sediment along Stillwater Slough near Stillwater below the confluence with New River (e.g., 14 ppm, Hoffman and others, 1990, p. 113).

The mercury contamination is significant. Hoffman and others (1990, p. 43) cited a baseline mercury concentration for soils in the western United States of 0.25 ppm. Above the Superfund site, mercury concentrations are low. Total mercury concentrations in river bottom sediment at Deer Run Road near Carson City were 0.078 ppm (78.4 nanogram per gram) (Hoffman and Thomas (2000, p. 5). Concentrations increase downstream to 4.13 ppm in the river at Fort Churchill. Below “Lahontan Reservoir”, there are wide variations from 0.204 ppm to 13.10 ppm in 10 sediment samples from Newlands canals and drains. 7 samples had greater than 1.0 ppm (Hoffman and Thomas (2000, p. 5). Previously, Hoffman and others (1990, p. 113) had collected 3 samples from various locations in “Carson Lake” with mercury concentrations of 3.8 to 18.0 ppm. The contaminated sediments provide a ready supply of inorganic mercury which can be converted to the more biologically harmful methylmercury by sulfate-reducing bacteria as conditions permit (Hoffman and Thomas, 2000, p. 2).

The U.S. Geological Survey and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service analyzed samples of detritus to better characterize potential biological pathways for mercury in the vicinity of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge. Detritus samples were collected from the upper 2 cm (0.8″) of the canal or lake bottom surface with a suction device (Rowe and others, 1991, p. 11). Detritus has a high proportion of organic matter and could indicate whether mercury is being accumulated in plants and small animals. The data of Rowe and others (1991) are shown on a map in Figure 15 of Hallock and others (1993, p. 53). “Carson Lake” Drain detritus had a mercury concentration of 4.70 ppm, which is higher than the sediment concentration. Other results for detritus from drains and ponds in “Carson Lake” are 0.58 (“Sprig Pond”) to 14.50 (Yarbrough Drain). The Pierson Drain, at the northeast edge of “Carson Lake” had 18.0 ppm. Mercury concentrations greater than 1.0 ppm extend upstream to the west and northwest of “Carson Lake”. There is a hot spot of mercury in detritus less than 5 km (3 miles) southwest of Fallon with 38.6 ppm (South Carson River Drain), 35.3 ppm (Upper Diagonal 2 Drain), and 13.6 ppm (Upper Diagonal Drain). This hot spot is probably due to tailings settling from floodwaters in and near the South Branch channel. According to Tuttle and others (2000), citing Persaud and others (1993), aquatic sediment mercury concentrations greater than 2 ppm can have severe effects on wildlife.

Mercury concentrations in detritus analyzed in the study of Rowe and others (1991) are strongly correlated with copper and lead. Bastin (1922, p. 44) wrote that “nearly all” the specimens of Comstock ore that he examined under the microscope had abundant galena, which has lead, and chalcopyrite, which has copper (N.B. a geologist could consider 10% by volume of these minerals “abundant” because they are so commonly rare). This is additional evidence for the transportation of mercury in mill tailings. However, the highest concentrations on the map of Hallock and others (1993, p. 53), 52.6 ppm and 97.8 ppm, are in the “Indian Lakes” area northeast of Fallon, where there is no known river channel.

Mercury has not generally been analyzed in waters of rivers, drains, or lakes of the “Carson Lake” and Stillwater Marsh areas because it is typically below the detection limits of the methods commonly used at the time. Moreover, the usual analysis of filtered water misses most of the mercury due to its tendency to adhere to particles (Hallock and others, 1993, p. 44). In the “Carson Lake” area, a filtered (“dissolved”) sample of “Carson Lake” Drain water collected in March 1987 had a concentration of 0.0002 mg/L mercury (Hoffman and others, 1990, p. 105) whereas an unfiltered (“total recoverable”) sample collected in May 1987 had 0.0024 mg/L (Hoffman and others, 1990, p. 107), more than 10 times higher.

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site – top

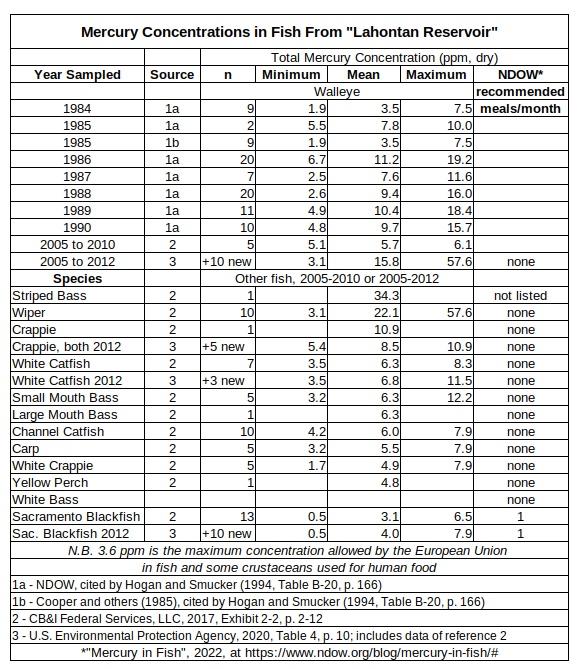

Mercury became a human health concern after studies in the 1970s and 1980s documented high concentrations of mercury in soils, fish, and ducks. The Nevada Health Officer issued a warning for consumption of fish from the Carson River and “Lahontan Reservoir” in 1987 and a warning for consumption of shoveler ducks from “Carson Lake” in 1989 (Ekechukwu, 1991, p. 4). NDOW had determined mercury concentrations of 1.9-19.2 ppm in walleye from “Lahontan Reservoir” with annual averages of 3.5-11.2 ppm for the years 1984-1987. 10 shoveler ducks collected in October 1987 had mercury concentrations in muscle of 2.1-55.7 ppm and a mean of 21.3 ppm (Rowe and others, 1991).

There are no plans to clean up the Carson River Mercury Superfund Site. It’s too big and the perpetrators are long dead. At most, Nevada Division of Environmental Protection has a Long-Term Sampling and Response Plan to warn people from living on or near the old mill sites in Operable Unit 1. This is to prevent incidental soil ingestion, particularly by those under the age of 6 (Nevada Division of Environmental Protection, 2018, p. 2). The “action level” for mercury in soil is 80 ppm (Nevada Division of Environmental Protection, 2018, p. 3). Mercury concentrations in sediment samples from the “Carson Lake” area (Hoffman and others, 1990) and in most of the Carson Desert (Tidball and others, 1991) are less than that.

The preferred alternative for the Environmental Protection Agency’s planned involvement in Operable Unit 2, which includes “Carson Lake” and the lakes of Stillwater National Wildlife Refuge, calls for land use controls to reduce exposure to soil with 80 ppm mercury or more (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021, p. 11-12). This assumes that residents planning dirt moving activity and prospective property buyers will get their soil tested. Eating game fish is not considered a health risk for recreational users in subarea B of Operable Unit 2, which includes “Lahontan Reservoir”, unless they are children. The only 2 human health risks in subarea D, which includes “Carson Lake”, are consumption of game fish by those practicing a traditional tribal lifestyle in areas off of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Reservation and consumption of sacramento blackfish caught in “Indian Lakes” and sold in Asian markets in California (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021, Table 1, p. 7). Consequently, there are no remedial action objectives for recreational anglers other than children or for any recreational duck hunters in Operable Unit 2.

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site – top

The Environmental Protection Agency has limited its involvement in Operable Unit 2. Due to high concentrations of mercury in fish (see the table of Mercury Concentrations in Fish From “Lahontan Reservoir”; wet weights in the original sources were multiplied by 3.6 to convert them to dry weights for consistency on this web site and with Hoffman and others, 1990, Table 7, p. 26), the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Nevada Division of Environmental Protection have posted warning signs within the Carson River Mercury Superfund Site since 2015. One such sign reads

- “”Health Advisory: Fish in these waters contain high levels of mercury and should not be eaten. (small print) Mercury is known to cause birth defects in infants and nerve damage in adults” (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2020, p. 14).

“State governments have the primary responsibility for protecting their communities from the risks associated with eating contaminated fish” (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2020, p. 13). Consequently, Nevada residents are protected from fish with high mercury concentrations by NDOW. Although NDOW merely repeats the health warnings of the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health, I haven’t been able to find mercury warnings or any additional information on a web page of the Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health or anywhere else.

NDOW has a conflict of interest when it comes to mercury-contaminated fish. The 2022 Nevada Fishing Regulations (at www.ndow.org) declared “Lahontan Reservoir” as a “warmwater anglers [sic] paradise” (p. 10). In the “Special Regulations” sections there are mercury warnings for those who read the fine print. For Churchill County, the line for the Carson River below “Lahontan Reservoir” has:

- “Health Advisory: The Nevada Division of Public and Behavioral Health has issued a health advisory recommending no consumption of any fish from the Carson River from Dayton to Lahontan Dam and all waters in Lahontan Valley due to elevated mercury levels in their flesh” (p. 45).

NDOW also has a “mercury in fish” web page (www.ndow.org/blog/mercury-in-fish/). It gives “recommended meals per month” as “none” for all species in “Lahontan Reservoir” except sacramento blackfish, for which 1 meal per month is okay.

In spite of the health advisories, NDOW regularly stocks “Lahontan Reservoir” and Carson River with fish that then grow up and become contaminated with mercury. The 2022 Nevada Fishing Regulations (p. 10) made a point to tell prospective anglers about the easy access from I-80 and the abundant camping opportunities at the “RV-friendly” “Lahontan Reservoir”. The fish possession limit there is 15 and it’s 25 for the Carson River. The limit allows up to 5 walleyes and up to 2 white bass or wipers. Depending on luck, a person could catch and possess 5 walleyes and 2 wipers averaging more than 7 ppm mercury each (refer to the means in Mercury Concentrations in Fish From “Lahontan Reservoir”) in 1 day. Because “It is unlawful for any person to cause through carelessness, neglect or otherwise any edible portion of any game bird, game mammal, game fish or game amphibian to go to waste needlessly” (p. 32; NRS 503.050), anyone who possesses mercury contaminated fish has to eat, or give to others to eat, all the “fillet meat” from the gill plates to the tail fins (p. 32) and all the methylmercury therein. Would that be dangerous?

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site – top

As an example, consider catching 5 walleye and 2 wipers at “Lahontan Reservoir”. Because there is mercury data for wipers but not white bass and weight data for white bass but not wipers, assume wipers weigh the same as white bass. Then, with an average walleye weight of 1,495 g (3.3 pounds) and an average wiper weight of 195 g (0.43 pounds) (Hogan and Smucker, 1994, Table B.20, p. 164-165), the weight of these 7 fish would likely be about 7,865 g. The edible weight is half that (Hogan and Smucker, 1994, p. 69), or 3,933 g. At a concentration of 7 ppm mercury, the edible portion of the 7 fish has 0.0275 g, or 27.5 mg, mercury. If those were the only mercury-contaminated fish eaten in a year, the daily consumption rate averaged over a year would be 0.0754 mg/day.

The same amount of mercury is more harmful in a light-weight person than in a heavy-weight person so the amount of mercury eaten per kg of body weight needs to be considered in determining dosage. For a person weighing 70 kg (154 pounds; Hogan and Smucker, 1994, Table E.1, p. 180, “adult resident”), the mercury dose would be 0.00108 mg mercury per day (averaged over the year) per kilogram of body weight.

The means in the table of Mercury Concentrations in Fish From “Lahontan Reservoir” are based on concentrations of dried samples. Dividing by 3.6 to convert to the mercury dose as measured in a biological sample that hasn’t been dried gives a dose of 0.000300 mg mercury (wet weight) per day per kilogram of body weight.

The Environmental Protection Agency’s reference dose for chronic oral exposure to methylmercury is 0.0001 mg mercury (wet weight) per day per kilogram of body weight. “An RfD is determined to be a rate of exposure that a person can experience over a lifetime without appreciable risk of harm” (“Technical Information on Development of FDA/EPA Advice about Eating Fish for Those Who Might Become or Are Pregnant or Breastfeeding and Children Ages 1-11 Years”). Eating those 5 walleyes and 2 wipers in 1 year would result in the consumption of about 3 times the amount of the Environmental Protection Agency’s reference dose for methylmercury. And that is just 1 day’s allowable catch. For those not carrying a fetus, eating those mercury-contaminated fish from “Lahontan Reservoir” in 1 year might be okay as long as no similarly contaminated foods were eaten year after year.

The mercury risk for duck hunters at “Carson Lake” is also worth considering. “Carson Lake is one of the most popular duck hunting areas in the state” (CBandI Federal Services, LLC, 2017, p. B-6-7, pdf page 321). Due to large year-to-year changes in the mercury concentrations in ducks and paucity of data, a single estimate of “average” mercury risk is not tenable. Consequently, I have calculated estimated mercury consumption for a hunter who bagged only shovelers and mallards at “Carson Lake” in 1987 (no green-winged teal data; high mercury in duck concentrations) and for a hunter who bagged only shovelers and green-winged teals in 1989 (no mallard data; low mercury in duck concentrations) using the hunter statistics and average duck weights in Hogan and Smucker (1994). 1973-1992 statistics provided by NDOW indicated hunters took an average of 11 ducks per year with 32% green-winged teals, 28% pintails, 22% mallards, and 18% shovelers (Hogan and Smucker, 1994, p. 70). Average weights were 340 g (0.75 pounds), 906 g (2.0 pounds), 1,261 g (2.8 pounds), and 612 g (1.3 pounds), respectively (Hogan and Smucker, 1994, p. 70). Hoffman and others (1990) and Rowe and others (1991) do not have mercury data for pintails. Mercury concentrations vary by species.

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site – top

Assuming the average hunter shot 11 shovelers and mallards in 1987 in the same ratio as in the 1973-1992 NDOW data, the hunter took home 5 shovelers and 6 mallards. The median mercury concentrations in 1987 were 21.5 ppm for shoveler muscle (n=10, mean 21.3, range 2.1-55.7, dry weight basis) and 2.4 ppm for mallard muscle (n=16, mean 2.9, range 0.13-7.9, dry weight basis). For a hunter who weighs 70 kg (154 pounds; Hogan and Smucker, 1994, Table E.1, p. 180) and doesn’t share the ducks and assuming 50% of the duck weight is edible, the mercury dose from the shovelers is 0.00129 mg per day per kg body weight and the dose from the mallards is 0.00036 mg per day per kg body weight. The total dose is 4.6 times the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s reference dose for methylmercury of 0.00036 mg per day per kg body weight (dry weight basis). If the hunter hunted ducks at “Carson Lake” only once every 5 years, had no other exposure to mercury, and was not pregnant, that might be okay. However, such high mercury concentrations in ducks are present in what little subsequent data I have found.

Assuming the average hunter shot 11 shovelers and green-winged teals in 1989 in the same ratio as in the 1973-1992 NDOW data, the hunter took home 4 shovelers and 7 green-winged teals. The median mercury concentrations in 1989 were 3.55 ppm for shoveler muscle (n=20, mean 7.1, range 0.86-36.0, dry weight basis) and 1.15 ppm for green-winged teal muscle (n=10, mean 2.70, range 0.18-13.0, dry weight basis). For a hunter who weighs 70 kg (154 pounds; Hogan and Smucker, 1994, Table E.1, p. 180) and doesn’t share the ducks and assuming 50% of the duck weight is edible, the mercury dose from the shovelers is 0.00017 mg per day per kg body weight and the dose from the green-winged teals is 0.000087 mg per day per kg body weight. The total dose is 70% of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s reference dose for methylmercury of 0.00036 mg per day per kg body weight (dry weight basis). This result makes it clear that measurements of annual mercury concentrations in ducks are critical for the effective management of mercury risk to duck hunters. Results for 2 years are poor estimators of the upper and lower limits of year-to-year changes in mercury in ducks. Most years could be better or most years could be worse.

In the 2022-2023 Nevada Small Game Hunting Regulations and Seasons, the daily limit for ducks is 7. There are no restrictions on duck hunting at the new “Carson Lake Wildlife Management Area”. The duck and coot seasons for 2022-2023 there are the usual mid-October to late January. The words “mercury” and “health” do not appear in the regulations.

The health risks identified by the Environmental Protection Agency in its plan for Operable Unit 2 mentions waterfowl consumption as a potential risk only for those practicing a traditional tribal lifestyle and only in the subareas upstream of Lahontan Dam (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2021, p. 7). I don’t know why the agency reached such an unsupportable conclusion but I can lay out how the Environmental Protection Agency minimized the risk to duck hunters. If you’re interested, read this. Otherwise, skip to Sediments of Lake Lahontan.

Carson River Mercury Superfund Site – top