2023 Fallon Range Training Complex Expansion

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake

Rawhide Hot Spring Lake

Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond

What Can We Learn from the Ponds in Gabbs Valley?

Gabbs Valley is really 2 valleys: western Gabbs Valley west of Fissure Ridge and eastern Gabbs Valley east of Fissure Ridge. They connect around the south end of Fissure Ridge.

Western Gabbs Valley

Western Gabbs Valley is somewhat round with dimensions of about 20 km (12 miles) north-south and 15-20 km (9-12 miles) west-east. It is bounded to the south and west by the Gabbs Valley Range and hills to the north separate it from Fairview Valley. On the 1:100,000-scale BLM map, there are stipple patterns indicative of wind-blown sand on the margins of the valley but nothing to indicate a large playa. The National Map has a stippled area for a playa in the northeastern part of the valley. The northern part of the valley is labeled “Alkali Flat” on the BLM map. In the northeastern corner of the valley, there is a cluster of “Cold Springs” and, about 1,800 m (5,900′) to the south, “Rawhide Hot Spring”. A small perennial lake is shown about 500 m (1,640′) north of the hot spring.

Elevations in western Gabbs Valley are 1,250-1,350 m (4,100-4,400′).

There isn’t much vegetation in western Gabbs Valley. What there is is desert scrub.

Western Gabbs Valley is mostly public land managed by the Stillwater Office of BLM. There are 2 large blocks of private land in the southeastern part of the valley and south of Fissure Ridge that have extensive hay fields irrigated by center-pivot sprinklers. There is also a square mile (260 hectares) of private land in the middle of the valley, which is undeveloped. There are small blocks of private land at Rawhide Hot Spring and at the cold springs to the north. There are well-maintained roads on the south and west sides of the valley leading to the Don Campbell geothermal plant and to the Rawhide mine. These connect to Nevada 361 to the east or Nevada 839 to the north.

Eastern Gabbs Valley

Eastern Gabbs Valley is up to 25 km (16 miles) wide and 35 km (22 miles) long. Fissure Ridge and the Monte Cristo Range lie on the west side of the valley and the Paradise Range and Lodi Hills on the east side. The 1:100,000-scale BLM map has a stipple pattern on the west side of the valley at the terminus of Phillips Wash.

Elevations range from 1,300 m (4,270′) to about 1,500 m (4,900′). The low spots are on the east side of the valley close to the town of Gabbs and on the west side next to Fissure Ridge.

Vegetation is desert scrub.

Eastern Gabbs Valley is also mostly public land. There are blocks of private land near the town of Gabbs, at the airport northwest of the town of Gabbs, and adjacent to the Phillips Wash stipple area next to Fissure Ridge. Nevada 361 runs along the east side of the valley through the town of Gabbs. A well-maintained road leads across the south end of the valley from Nevada 361 past the ranches south of Fissure Ridge to Ormat’s Don Campbell geothermal plant.

By the end of 2029, parts of eastern and western Gabbs Valley will be closed to the public and fairy shrimp ponds in those areas, if any, will no longer be accessible. The Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Navy’s expansion of the Fallon Range Training Complex’s bombing ranges was completed in January 2020 (links to multiple pdf files under “2020 FRTC Modernization Final EIS” at frtcmodernization.com/Documents). Congress authorized the expansion and related activities when it signed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 (www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ263/PLAW-117publ263.pdf) in December 2022. The expansion moves the southern boundary of range B-17 33 km (20 miles) to the south and widens the range from 14 km (8.4 miles) to about 30 km (18 miles). The new B-17 range covers the eastern end of western Gabbs Valley and most of eastern Gabbs Valley. The new B-17 boundary is 6 km (3.6 miles) from Gabbs at its closest.

Before the expanded area of range B-17 becomes operational, 20 km (12 miles) of Nevada 361 north of Gabbs have to be moved up to 4.5 km (2.7 miles) (minimum without considering terrain or environmental concerns) to the east and 30 km (18 miles) of the natural gas pipeline to the magnesite mine in Gabbs have to be moved 2-14 km (1.2-8.4 miles) to the south of the new boundary of B-17 (2020 FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-50, pdf page 194). In addition, private lands at Rawhide Hot Spring and at the cold springs at the northeastern end of western Gabbs Valley and a block of private land south of Lower Phillips Well in Eastern Gabbs Valley will be purchased by the federal government. According to the “FRTC Modernization Timelines by Ranges” graphic, the replacement of part of Nevada 361 is projected to be completed by July 2029 and the replacement of part of the gas pipeline and the purchase of private lands are projected to be completed by October 2028. Fencing is expected to be completed by July 2029. All of this is contingent on Congress providing sufficient funding in a timely manner. The Navy could conceivably tear up roads or otherwise restrict access to the expanded part of B-17 range at any time. Mining activity and geothermal leasing have already been prohibited on the expansions.

Below, I digress on the Navy’s negligence and willful ignorance as exemplified by the EIS. If you’re not interested, skip ahead.

2023 Fallon Range Training Complex Expansion

In the following discussion, “FEIS” refers to the documents linked in the list under the heading “2020 FRTC Modernization Final EIS” on the frtcmodernization.com/Documents web page.

The locations of Fallon Range Training Complex were not chosen with an eye to resource conflicts or future expansion. Division of the training areas into 5 locations implies an early recognition of the poor suitability of the Fallon area. While the ranges avoided populated and farming areas, B-17 took over most of the Fairview Mining District (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, Mineral Potential Report for the Fallon Range Training Complex Modernization: Technical Report for ManTech International Corporation, Figure 3-3, p. 47), which has produced gold and silver. B-16, B-17, and the Dixie Valley Training Area are in close proximity to several other mining districts with the potential for gold, silver, lead, copper, tungsten, barite, or fluorite production (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, p. 55-76). The potential for additional gold, silver, lead, and tungsten production is considered high, with high certainty (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, Table 4-2, p. 96-97). 8 districts in or near the ranges have high potential for gold. B-20 has moderate potential with high certainty for sodium chloride and moderate potential with low certainty for lithium (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, p. 121-122, 141).

The Fallon ranges also conflict with geothermal resources. B-17, B-20, and the Dixie Valley Training Area are on or adjacent to areas with high potential for geothermal resources with high or moderate certainty (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, Figure 4-16, p. 132). B-19 cannot be expanded to the south because of the Walker River Paiute Reservation or to the west because of US 95. B-17 cannot be expanded to the north because of US 50. B-20 was perversely located on the railroad checkerboard of mixed public and private land so about half of its area had to be purchased from land owners.

Conflicts with highways and pipelines (B-17), private land (B-20), metallic mineral resources (B-16, B-17, Dixie Valley Training Area), industrial mineral resources (B-20), and geothermal resources (B-17, B-20, Dixie Valley Training Area) make expanding the existing ranges a bad idea. Nonetheless, the Navy decided in its 2015 “Ninety Days to Combat” report, if not earlier, to seek expansion of B-17, B-20, and Dixie Valley Training Area. For then on, it singlemindedly pursued that objective.

The Navy’s EIS considered no alternatives other than expanding the existing bombing ranges even though Section 1502.14 of Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations, states that federal “agencies shall:

(a) Rigorously explore and objectively evaluate all reasonable alternatives . . .”

Moreover, U.S. Code, Title 42, Chapter 55, Section 4332, states:

“(2) all agencies of the Federal Government shall-

(E) study, develop, and describe appropriate alternatives to recommended courses of action in any proposal which involves unresolved conflicts concerning alternative uses of available resources . . .”

The Navy used various excuses to justify not analyzing alternatives. Cost was popular. To eliminate the Nevada Test and Training Range as a possible alternative, the Navy wrote: “Converting this range to accommodate Navy training would be technically feasible but not economically feasible” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-59). Similarly, “It would take in excess of 1.5 billion dollars to replicate the required infrastructure of facilities and training systems that are specific to naval aviation and Naval Special Warfare requirements at NAS Fallon and FRTC at the Barry M. Goldwater Range complex” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-62). And, “It would take in excess of 1.5 billion dollars to replicate the required infrastructure of facilities and training systems that are specific to naval aviation and Naval Special Warfare requirements at NAS Fallon and FRTC at the White Sands Missile Range” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-62). As for a new training area, “NAS Fallon and FRTC represent over 1.5 billion dollars in infrastructure development that the Navy cannot replicate easily or affordably at any other known location in the continental United States or abroad” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-62). The figure $1.5 billion was not itemized or explained in the EIS and is not supported by any other document. How much of existing infrastructure, such as radar equipmemt, could be moved instead of purchased anew was not mentioned. For all practical purposes, the Navy made the number up. Even if true, the cost argument is irrelevant to the identification of reasonable alternatives, as explained by the Council on Environmental Quality below.

In dismissing the use of existing bombing ranges as possible alternatives, the EIS invariably cited scheduling conflicts that would preclude the speed and tempo of activity the Navy wants. For the Nevada Test and Training Range: “While developing training systems is possible at the Nevada Test and Training Range, the U.S. Air Force and U.S. Air Force-sponsored training use up nearly all of the complex’s available training time. Without terminating the Air Force’s existing testing and training activities, the range as currently configured would not be able to support the tempo and level of Navy training” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-60). There is no mention of the Tonopah Test Range Airport in the Nevada Test and Training Range, which has been little used since 1992 (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tonopah_Test_Range_Airport). F-117s have been stored in the hangars since 2008 and the airport may be used for drone operations.

Barry M. Goldwater Range: “Additionally, without terminating the existing training activities, the range as currently configured would not be able to support the tempo and level of Navy training, or the scheduling priorities required by the Optimized Fleet Response Plan. Moreover, even if the Navy were to undertake the required conversion, doing so would not eliminate the scheduling conflicts . . .” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-62). Not mentioned is that scheduling conflicts could be greatly reduced by flying out of Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Tucson, which hosts only a fighter wing flying close-air-support A-10 aircraft (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Davis-Monthan_Air_Force_Base), rather than out of Luke Air Force Base west of Phoenix or by using the Gila Bend Auxiliary Field.

For the Navy’s Southern California Range Complex: “Moreover, even if the Navy were to take over the range complexes for Carrier Air Wing training, doing so would not eliminate the scheduling conflicts that would severely impact tempo requirements . . .” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-61).

For the China Lake – Fort Irwin – Edwards Air Force Base complex: “The joint testing primacy of the R-2508 Complex schedule cannot support the tempo and level of Navy training, or the scheduling priorities required by the Optimized Fleet Response Plan” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-61). The 2 China Lake training areas are at least 58 km (35 miles) long. If China Lake doesn’t need the 50 km (30 miles) long weapons danger zones needed by Fallon Range Training Complex (e.g., Joint Direct Attack Munitions in FEIS, v. 1, Table 1-2, p. 1-17, pdf p. 101), then moving some China Lake operations to Fallon and some Fallon operations to China Lake could reduce scheduling conflicts.

While Fallon Range Training Complex management could not force scheduling changes at other bombing ranges, such alternatives are reasonable because the Department of Defense could decide at a higher level to make changes to improve the efficiency of existing bombing ranges. The Department of Defense could even decide that the tempo the Navy wants could be reduced or that schedules could be changed at other ranges without compromising the training objectives.

In the “Forty Most Asked Questions Concerning CEQ’s [Council on Environmental Quality] National Environmental Policy Act Regulations, Memorandum for Federal NEPA Liaisons, Federal, State, and Local Officials and Other Persons Involved in the NEPA Process” (March 16, 1981), question 2b addresses both the cost and scheduling excuses.

“2b. Must the EIS analyze alternatives outside the jurisdiction or capability of the agency or beyond what Congress has authorized?

[Answer.] An alternative that is outside the legal jurisdiction of the lead agency must still be analyzed in the EIS if it is reasonable. A potential conflict with local or federal law does not necessarily render an alternative unreasonable, although such conflicts must be considered. Section 1506.2(d). Alternatives that are outside the scope of what Congress has approved or funded must still be evaluated in the EIS if they are reasonable, because the EIS may serve as the basis for modifying the Congressional approval or funding in light of NEPA’s goals and policies. Section 1500.1(a).”

Although $1.5 billion may sound like a lot of money, the inflation-adjusted cost of a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier is more than $9 billion (en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nimitz-class_aircraft_carrier) and the Navy somehow managed to buy a few. The argument that the federal government could not afford to spend $1.5 billion to move the Navy’s pilot training areas to locations that allow realistic exercises with modern weapons (see below) is not credible. What good is an aircraft carrier without well trained pilots?

The Navy’s irrelevant arguments and failure to consider alternatives that were meaningfully different could be considered a willful violation of the National Environmental Policy Act but I’ll just call it negligence.

The economic analysis in the Navy’s EIS selectively excluded important information. The economic analysis in the EIS considered the effects of reductions in areas available for grazing and hunting but nothing else. The maximum grazing loss was estimated at $12.8 million ($639,400 annually; FEIS, v. 2, p. 3.13-48, pdf page 360) and the hunting loss at $6.6 million over 20 years ($328,740 annually; FEIS, v. 2, p. 3.13-56, pdf page 368).

What is most notable about the economic analysis is what it left out. There is no word on how much the 1,423 civilian and military personnel stationed at Fallon Naval Air Station and the 20,000 annual transients (FEIS, p. 3.13-9, v. 2, pdf p. 321) contribute to the local economy. What does it mean when a military service fails to tell the local community, the host state, and the American public what the economic effects of modifying, moving, or closing a base would be? Base relocation, which is necessarily a reasonable alternative for Fallon Range Training Complex, is usually of great interest to the public and to politicians. Willful ignorance.

The EIS has no estimates of lost economic activity due to mining exploration and production. A gold mine with about 13.6 million tonnes (15 million tons) of ore grading 2.06 grams/tonne (0.06 troy ounces/ton) was considered a “Reasonably Foreseeable Development” (i.e., in the absence of the current and expanded bombing ranges) (FEIS, v. 1, p. 3.3-47, pdf p. 397) but it was not worthy of economic analysis by the Navy. Assuming 90% recovery of gold and a price of $64.31/g ($2,000/ounce), lost gold sales would be worth about $1.6 billion for those reasonably foreseeable 900,000 troy ounces. Mine construction, operating, and reclamation costs could amount to $125 million or more. That was the total cost estimated for the much smaller Isabella-Pearl Mine in Mineral County, which had proven and probable gold reserves of 2.7 million tonnes at a grade of 2.2 grams/tonne (Brown, F.H., Garcia, J.R., Devlin, B.D., and Lester, J.L., 2017, Report on the Estimate of Reserves and the Feasibility Study for the Isabella Pearl Project, Mineral County, Nevada: Technical Report for Walker Lane Minerals Corporation, 264 p.) and began operations in 2019 (Gold Resource Corporation, October 7, 2019 press release, “Gold Resource Corporation Declares Commercial Production at Isabella Pearl Gold Mine, Mineral County, at www.goldresourcecorp.com). Willful ignorance.

In addition, mineral exploration activity on the current and proposed area of range B-17 and the Dixie Valley Training Area could amount to $24 million over 20 years without the bombing ranges. This estimate is based on the 723 mining claims I counted on the proposed additions to B-17 and Dixie Valley Training Area in 2018 (using BLM’s LR2000 database of mining claims at reports.blm.gov/reports/lr2000/#) and 96 claims that I assumed would be staked in the Fairview District when B-17 is opened to the public. 2016 statewide spending on precious and base metals exploration was $286 million (Ressel, M.W. and Davis, D.A., 2017, Nevada Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration Survey, 2015/2016: Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Technical Report, 16 p.). Nevada Division of Minerals Open Data Site showed 193,700 mining claims statewide in October 2018 (at data-ndom.opendata.arcgis.com/pages/mining-claims). Assuming annual expenditures are the same for all claims in Nevada and don’t change from year to year, $1,477 would be spent on each claim annually. 20 years x $1,477/year x 819 claims = $24 million. This is only a ballpark estimate but ignoring mineral exploration is willful ignorance.

The Navy’s EIS also failed to mention economic activity lost due to the exclusion of geothermal exploration and production. The Navy’s consultants considered the discovery of geothermal resources sufficient for the production of 20-30 megaWatts of power reasonably foreseeable (Golder Associates, Inc., 2018, Mineral Potential Report for the Fallon Range Training Complex Modernization: Technical Report for ManTech International Corporation, 215 p.). The Navy reduced the power output to 15 megaWatts for the EIS (FEIS, v. 1, p. 3.3-48, pdf p. 398). Annual sales for a 20 megaWatt plant could be around $12.5 million per year, or $250 million over 20 years, if the sales price is the same as that for Ormat Technologies’ 24-megawatt Tungsten Mountain geothermal plant in Edwards Creek Valley, eastern Churchill County (December 21, 2017 press release at www.ormat.com). According to the Geothermal FAQs on the web page of the Office of Energy Efficiency & Renewable Energy (www.energy.gov/eere), a 20-megawatt plant would have construction and operating costs of $113 million over 20 years, assuming it operates 90% of the time. Lost geothermal exploration expenditures are likely greater than $4 million/year, or $80 million over 20 years. This is based on the $54 million spent state-wide in 2011 (Muntean, J.L., Garside, L.J., and Davis, D.A., 2013, Nevada Mineral and Energy Resource Exploration Survey 2011: Presentation, Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, 48 p. at www.nbmg.urn.eduu) and assumes 7.5% of those exploration dollars would be spent in the area of B-17 and Dixie Valley Training Area, taking into account the number of geothermal resource areas identified in Nevada. This may be conservative as existing geothermal plants in Gabbs Valley and Dixie Valley prove economically viable resources are present. The Navy may allow some geothermal activity in Dixie Valley Training Area if the operator agrees to “required design features” (FEIS, v. 2, p. 5-24, pdf p. 634), like buried transmission lines. Some geothermal exploration expenditures might not be lost but few companies are likely to take the risk. Willful ignorance.

Thanks to the Navy’s omissions, a negative economic impact over 20 years of $19.4 million due to reduced grazing and hunting is more like $2.2 billion when mining and geothermal losses are included.

The Navy’s EIS didn’t mention how much the project would cost or how long it would take. There is no estimate for the cost of “modification of range infrastructure to support modernization” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 2-1, pdf p. 85). The EIS did identify a few projects that would be necessary but provided no estimates of cost. The federal government will have to purchase 264 square kilometers (102 square miles, 65,336 acres) of private land (FEIS, v.1, p. 2-45, pdf page 189) for the expansion. By searching county records, I found that the taxable value of these lands was about $1.7 million in 2018. A fair purchase price could be higher. The federal government will have to move a natural gas pipeline so that 30 km (18 miles) of it do not cross range B-17 (FEIS v. 1, p. 2-50, pdf 194). At an average cost of $75,000 per inch-mile (ICF Foundation, 2009, Natural Gas Pipeline and Storage Infrastructure Projections Through 2030: Technical Report submitted to INGAA Foundation, 100 p.), it would cost $18 million to build at least 50 km (30 miles) of a 20.3 cm (8″) diameter pipeline from Gabbs around the south end of range B-17. The federal government will have to replace 20 km (12 miles) of Nevada 361 (FEIS volume 1, p. 2-50, pdf 194) with at least 22 km (13.2 miles) of new highway that goes outside the eastern boundary of range B-17 north of Gabbs. The web page of the American Road & Transportation Builders Association indicates a new rural 2-lane highway would generally cost $2-3 million per mile to build (www.artba.org/about/faq/). Using the lower limit here because land acquisition costs would probably be less than the national average, the cost would be $26.4 million. That adds up to roughly $46 million of costs that the Navy didn’t attempt to tell the American public about. Willful ignorance.

Federal agencies usually tell those people who will be most affected by a proposed project something about the project. Not the Navy. The Navy made no effort to contact the land owners who would lose their lands or the mining claim owners who would lose their mining claims or inform them of their impending losses. Public meetings in Fallon, Lovelock, and Hawthorne fall a bit short. Negligence.

The Navy also did a poor job of communicating with affected tribes and failed to gain much, if any, support. The Navy’s decision to release the draft EIS without involving tribes did not go over well. In a November 16, 2018 letter, Len George of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe wrote: “We were surprised to learn toward the end of the meeting, and only when asked directly, that the draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) is being published today. This was especially surprising, given that you stated at the meeting that discussions with the Tribes to identify cultural sites, their importance, and possible ways to protect are just underway” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-638, pdf p. 660). In a November 20, 2018 letter, Ronnie Snooks of the Yomba Shoshone Tribe wrote: “The pretense of the meeting was to identify concerns and cultural areas in order to protect these areas from the impacts of the proposed bombing locations. During that meeting it was revealed that the DEIS was due to be released on Friday, November 16, 2018, two days after the meeting scheduled with Indian Tribes. This clearly indicates that the Naval Air Station Fallon will not be including tribal input derived from that meeting into the DEIS” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-664, pdf p. 686).

Comments by tribal leaders on the draft EIS were generally not supportive. For example, the subheadings for “Analytical Flaws” in Len George’s February 14, 2019 letter were “Incorrect Environmental Baseline”, “Failure to Consider Impacts to the Tribe and its Members”, “Improper and Premature Assessment of Impacts to Cultural, Sacred, and Historic Sites”, and “Environmental Justice: The DEIS Fails to Consider Fact That Tribes Will Bear Disproportionate Impacts”. “Specific Additional Concerns” included:

- “The Navy does not provide a reasonable range of alternatives – at least one alternative must completely avoid the Fox Peak ACEC [Area of Critical Environmental Concern, as designated by the BLM]” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-649-650, pdf p. 671-672).

- “The tribe notes that the cultural impacts for purposes of NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] are much broader than those considered under NHPA [National Historic Preservation Act], and the two statutes should not be conflated” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-650, pdf p. 672).

- “The Tribe is concerned that the ‘Site Visit Management Program’ described at DEIS 2-34 would not prioritize use for non-military purposes and would, as a practical matter, severely limit or eliminate access for Tribal members” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-651, pdf p. 673).

- “As discussed further in the appended expert report, the use of speech interference as the measure of noise disturbance fails to take into account the importance of quiet reflection at culturally significant areas and is an overly narrow scope of analysis” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-651, pdf p. 673).

The quotations in the above paragraph should not be considered representative of, and do not do justice to, Mr. George’s 10 page letter.

A February 14, 2019 letter from Amber Torres, Walker River Paiute Tribe, was no kinder:

- “To this day, the Navy has not taken responsibility for encumbering tribal land (est. 6,000 acres) since the 1940’s, which has been contaminated with live and inert ordinance, caused historical damage to range wells and facilities and has left such land useless as this land cannot be totally cleaned of ordinance and bombs” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-669, pdf p. 691).

- “The Tribe opposes the land expansion and believes that the additional training will lead to further negative impacts and bombing to reservation lands” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-669, pdf p. 691).

- “The expansion, and training enabled by the expansion, would eliminate access to hundreds of thousands of acres of ancestral lands and cause irreparable harm to the Tribe’s cultural and spiritual sites” (FEIS, v. 4, p. F-669, pdf p. 691).

The quotations above should not be considered representative of, and do not do justice to, Ms. Torres’s 10 page letter and these selections of tribal comments do not reflect the main points or the entirety of tribal concerns. They are merely meant to illustrate some of the Navy’s failures.

In addition to lapses in the preparation of the EIS, in communicating with affected individuals, and in addressing concerns by affected Tribes, the Navy failed to comply with the recommendations of its own “Ninety Days to Combat” report, which it wrote in 2015 to justify expansion of the bombing ranges in the first place. The sizes needed for the bombing ranges are determined by weapons danger zones, which Figure 1-3 (FEIS, v. 1, p. 1-13, pdf p. 97) suggests are equivalent to the release ranges for the various weapons used by the Navy. When the Navy compared the release ranges to the areas available adjacent to the existing bombing ranges, it found that acquiring such large areas of land “would be both unattainable as a practical matter and undesirable because of the potential level of impacts on the surrounding area and communities” (FEIS, v. 1, p. 1-14, pdf p. 98). Consequently, it reduced the weapons danger zones to “tactically acceptable” distances. These changes are shown in Table 1-2 (FEIS, v. 1, p. 1-17, pdf p. 101). For example, the release range for Joint Direct Attack Munitions is reduced from 14.9 miles (24.8 km) to 11.5 miles (19.2 km) and the range of acceptable attack azimuths is reduced from 360 degrees to 180 degrees. In addition, the tactically acceptable weapons danger zone for Dual-Mode Laser-Guided Bomb was reduced to the area “contained within the Joint Direct Attack Munition WDZ” even though its release range in Table 1-2 is 16.1 miles (26.8 km), i.e., a reduction to 70% of the release range. In essence, the Navy fabricated weapons danger zones to fit within expansions of the current bombing ranges that it thought it could get away with. The Navy sacrificed realistic training to its perverted attachment to Churchill County. That may or may not make a difference in real combat but the pilots can’t complain in any case.

The Navy’s failures could perhaps be overlooked if there were simply no other options. There are, in fact, several realistic options. Moving to an existing bombing range would allow the Navy to achieve full compliance with the release range of Dual-Mode Laser-Guided Bombs. The Nevada Test and Training Range can easily accommodate 360-degree weapons danger zones with radii of 21 miles (35 km). Barry M. Goldwater Range is (130 miles) long with an eastern half mostly about 35 km (21 miles) wide and the western half up to 72 km (43 miles) wide. White Sands Missile Range is approximately a rectangle 165 km (99 miles) long and 65 km (40 miles) wide but with a cut-out for White Sands National Monument. No highways or pipelines would have to be moved. There would be no private land to buy. No additional mineral, geothermal, recreational, biological, or grazing resources would be affected. No new tribal concerns would have to be dealt with. Air space modifications would be minimal. The most significant impacts would probably be the increase in a transient population of trainees and more noise.

There are also at least a few large areas of public land in Nevada that could be converted to bombing ranges with larger weapons danger zones than the expansions of ranges B-17 and B-20. At least one area could provide a circular weapons danger zone 50 km (30 miles) in diameter. Moving to just about any area of public lands outside the railroad checkerboard, where B-20 is located, would result in less private land to purchase. Avoiding paved highways is easy in Nevada but avoiding pipelines and power lines could be a little trickier. Publications of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology and the United States Geological Survey could be used to avoid geothermal resources (e.g., Penfield and others, 2010, Nevada Geothermal Resources, Map 161) and most mining districts that have the potential for the discovery of significant new mineral resources. Recreational and biological impacts would probably be similar in most areas of the state. Grazing impacts would be greater in the north and less in the south. Tribal concerns are unknowable in advance but there probably aren’t many other areas that have the significance of Fox Peak or that are as close to existing reservations. The fact that the Navy didn’t find such areas for a new bombing range is good evidence that it didn’t look for them.

None of the Navy’s failings mattered to Congress. The Navy’s plan wasn’t quite rubber stamped; approval was delayed for a couple of years. When Congress got around to authorizing the expansion of Fallon Range Training Complex in the National Defense Authorization Act for fiscal year 2023 (NDAA, National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 at www.congress.gov/117/plaws/publ263/PLAW-117publ263.pdf), it apparently didn’t try to modify the Navy’s preferred alternative. Instead, Congress created a potpourri of bribes and pay offs that would put a pork barrel to shame. None of it was in the EIS and Congress doesn’t have to consider the human or environmental consequences of its own actions, only federal agencies do. The American public has no recourse and can only marvel at the scope of what has become national defense.

I have no personal interest in the expansion of Fallon Range Training Complex and do not judge whether the pay offs are deserved or not. I merely list them for amusement. One of the most amusing things is how long the list is. The section of interest in the NDAA (aka Public Law 117-263) is Title XXIX “Fallon Range Training Complex”.

Section 2901. “Military Land Withdrawal for Fallon Range Training Complex”. This amends Public Law 113-66 “Subtitle G – Fallon Range Training Complex, Nevada” by adding new sections, as enumerated below.

- Section 2982. Management of Withdrawn and Reserved Land.

(b)(1) Dixie Valley Training Area shall be managed by the Secretary of the Interior but (2)(B) the Secretary of the Navy must approve the use of any “equipment used to transmit and receive radio signals”.

(c)(3) “. . . the Secretary of the Navy shall transfer to Churchill County, Nevada, $20,000,000 for

deposit in an account designated by Churchill County, Nevada, to resolve the loss of public access and multiple use within Churchill County, Nevada.” - Section 2988. Resolution of Walker River Paiute Tribe Claims.

(a) “. . . the Secretary of the Navy shall transfer $20,000,000 of amounts appropriated to the Secretary of the Navy for operation and maintenance to an account designated by the Walker River Paiute Tribe (referred to in this section as the ‘Tribe’) to resolve the claims of the Tribe against the United States for the contamination, impairment, and loss of use of approximately 6,000 acres [24.3 square kilometers, 9.4 square miles] of land that is within the boundaries of the reservation of the Tribe.”

(c)(3)(A) “. . . the land described in paragraph (4) . . . shall be (ii) made part of the existing reservation of the Tribe.”

(c)(4) “. . . the land to be held in trust for the benefit of the Tribe under paragraph (3)(A) is the approximately 8,170 acres [33 square kilometers, 12.8 square miles] of Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Reclamation land located in Churchill and Mineral Counties . . .” - Section 2989. Land to be Held in Trust for the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe.

(a)(1) “. . . the land described in paragraph (2) shall be . . . (B) made part of the reservation of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe.”

(a)(2) “The land referred to in paragraph (1) is the approximately 10,000 acres [40.5 square kilometers, 15.6 square miles] of land administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the Bureau of Reclamation . . .” - Section 2990. Numu Newe Cultural Center.

(a) “. . . the Secretary of the Navy shall provide financial assistance to a cultural center established and operated by the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe and located on the Reservation of the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe . . .”

(b)(1) “$10,000,000 for the development and construction of the Center; and (2) $10,000,000 to endow operations of the Center.” - Section 2993. Treatment of Livestock Grazing Permits.

(c) “If replacement forage cannot be identified under subsection (a), the Secretary of the Navy shall make full and complete payments to Federal grazing permit holders for all losses suffered by the permit holders as a result of the withdrawal or other use of former Federal grazing land for national defense purposes . . .”

(d) “The Secretary of the Navy shall . . . (2) compensate the holders of grazing allotments described in paragraph (1) for authorized permanent improvements associated with the allotments.” - Section 2995. Reduction of Impact of Fallon Range Training Complex Modernization.

(a)(5)(B) “Make payments to the holders of mining claims described in subparagraph (A), subject to the availability of appropriations.”

(a)(10) “Notify affected water rights holders by certified mail and, if water rights are adversely affected by the modernization [e.g., become inaccessible] and cannot be otherwise mitigated, acquire [i.e., buy] [holders’] existing and valid State water rights.”

(a)(15) “Fund 2 conservation law enforcement officer positions at Naval Air Station Fallon.”

(a)(17) “Enter into an agreement for compensation from the Secretary of the Navy to Churchill County, Nevada, and the counties of Lyon, Nye, Mineral, and Pershing in the State of Nevada to offset any reductions made in payments in lieu of taxes.” - Section 2996. Dixie Valley Water Project.

(c) “. . . the Navy shall compensate Churchill County, Nevada, for any cost increases for the Dixie Valley Water Project that result from any design features required by the Secretary of the Navy to be included in the Dixie Valley Water Project.” - Section 2998. Tribal Liaison Office. “The Secretary of the Navy shall establish and maintain a dedicated Tribal liaison position at Naval Air Station Fallon.”

The following sections are new, not amendments of Public Law 113-66.

- Section 2902. Numu Newe Special Management Area [not closed to mining and geothermal leasing].

(b) “To protect, conserve, and enhance the unique and nationally important historic, cultural, archaeological, natural, and educational resources of the Numu Newe traditional homeland, subject to valid existing rights, there is established in Churchill and Mineral Counties, Nevada, the Numu Newe Special Management Area . . .”

(c) “The Special Management Area shall consist of the approximately 217,845 acres [882 square kilometers, 340 square miles] of public land . . .” - Section 2903. National Conservation Areas [closed to mining and geothermal leasing].

(a)(2)(A) “To conserve, protect, and enhance for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations the cultural, archaeological, natural, wilderness, scientific, geological, historical, biological, wildlife, educational, recreational, and scenic resources of the Conservation Area, subject to valid existing rights, there is established the Numunaa Nobe National Conservation Area . . .”

(a)(2)(B)(i) “The Conservation Area shall consist of approximately 160,224 acres [648 square kilometers, 250 square miles] of public land in Churchill County . . .”

(b)(2)(A) “To protect, conserve, and enhance the unique and nationally important historic, cultural, archaeological, natural, and educational resources of the Pistone Site on Black Mountain, subject to valid existing rights, there is established in Mineral County, Nevada, the Pistone-Black Mountain National Conservation Area.”

(b)(2)(B)(i) “The Conservation Area shall consist of the approximately 3,415 acres [13.8 square kilometers, 5.3 square miles] of public land . . .” - Section 2905. Wilderness Areas in Churchill County, Nevada [closed to mining and geothermal leasing].

(b)(1)(A) “Certain Federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, comprising approximately 128,362 acres [519 square kilometers, 200 square miles] . . . shall be known as the ‘Clan Alpine Mountains Wilderness’ “.

(b)(1)(B) “Certain Federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, comprising approximately 32,537 acres [132 square kilometers, 51 square miles] . . . shall be known as the ‘Desatoya Mountains Wilderness’ “.

b)(1)(C) “Certain Federal land managed by the Bureau of Land Management, comprising approximately 7,664 acres [31 square kilometers, 12.0 square miles] . . . shall be known as the ‘Cain Mountain Wilderness’ “.

(f)(4)(B) “. . . neither the President nor any other officer, employee, or agent of the United States shall fund, assist, authorize, or issue a license or permit for the development of any new water resource facility within a wilderness area.” - Section 2906. Release of Wilderness Study Areas.

(a) “. . . the public land in Churchill County, Nevada, that is administered by the Bureau of Land Management in the following areas has been adequately studied for wilderness designation:

(1) The Stillwater Range Wilderness Study Area.

(2) The Job Peak Wilderness Study Area.

(3) The Clan Alpine Mountains Wilderness Study Area.

(4) That portion of the Augusta Mountains Wilderness Study Area located in Churchill County, Nevada.

(5) That portion of the Desatoya Mountains Wilderness Study Area located in Churchill County, Nevada.” - Section 2907. Land Conveyances and Exchanges.

(b)(1) “. . . the Secretary of the Interior shall convey, subject to valid existing rights and paragraph (2), for no consideration, all right, title, and interest of the United States in approximately 6,892 acres [27.9 square kilometers, 10.8 square miles] of Federal land to Churchill County, Nevada, and 212 acres [0.8 square kilometers, 0.3 square miles] of land to the City” [of Fallon] for “a new fire station” [(a)(2)(A)], “expansion of an existing waste-water treatment facility” [(a)(2)(B)], “expansion of existing gravel pits” [(a)(2)(C)], “expansion of an existing City landfill” [(a)(2)(D)], and “public recreational facilities” [(b)(2)].

(c) “The Secretary of the Interior shall seek to enter into an agreement for an exchange with Churchill County, Nevada, for the land identified as ‘Churchill County Conveyance to the Department of Interior’ in exchange for the land administered by the Secretary of the Interior identified as ‘Department of Interior Conveyance to Churchill County’ . . .” - Section 2908. Checkerboard Resolution.

(b)(1) “. . . the Secretary of the Interior shall offer to exchange land identified for exchange under paragraph (3) for private land in Churchill County, Nevada, that is adjacent to Federal land in Churchill County, Nevada, if the exchange would consolidate land ownership and facilitate improved land management in Churchill County . . .” - Section 2922. Conveyances to Lander County, Nevada.

(a) ‘. . . not later than 60 days after the date on which the County identifies and selects the parcels of Federal land for conveyance to the County from among the parcels identified on the Map as ‘Lander County Parcels BLM and USFS’ and dated August 4, 2020, the Secretary concerned shall convey to the County, subject to valid existing rights and for no consideration, all right, title, and interest of the United States in and to the identified parcels of Federal land (including mineral rights) for use by the County for watershed protection, recreation, and parks.”

(b)(1) . . . the Secretary concerned shall convey to the County, subject to valid existing rights, including mineral rights, all right, title, and interest of the United States in and to the parcels of Federal land identified on the Map as ‘Kingston Airport’ for the purpose of improving the relevant airport facility and related infrastructure.” - Part II – Lander County Wilderness Areas, Section 2932. Designation of Wilderness Areas [closed to mining and geothermal leasing].

(a) “. . . the following land in the State of Nevada is designated as wilderness . . .

(1) . . . approximately 6,386 acres [25.8 square kilometers, 10.0 square miles], generally depicted as ‘Cain Mountain Wilderness’ on the Map, which shall be part of the Cain Mountain Wilderness designated by section 2905(b) of this title.”

(2) “. . . approximately 7,766 acres [31.4 square kilometers, 12.1 square miles], generally depicted as ‘Desatoya Mountains Wilderness’ on the Map, which shall be part of the Desatoya Mountains Wilderness designated by section 2905(b) of this title.” - Section 2933. Release of Wilderness Areas.

(a) “. . . the following public land in the County has been adequately studied for wilderness designation:

(1) The approximately 10,777 acres [43.6 square kilometers, 16.8 square miles] of the Augusta Mountain Wilderness Study Area within the County that has not been designated as wilderness by section 2902(a) of this title.

(2) The approximately 1,088 acres [4.4 square kilometers, 1.7 square miles] of the Desatoya Wilderness Study Area within the County that has not been designated as wilderness by section 2902(a) of this title.”

There is more – Title XXIX is 34 pages long – but the above are some of the quantified or easily defined pay offs. Ethnographic and cultural surveys and new management plans were required as were various agreements between the Secretaries of Interior and Navy and Tribes. The monetary pay offs to Churchill County, the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe, and the Walker River Paiute Tribe increase the cost of the Fallon Range Training Complex expansion by $60 million and unquantified pay offs to grazing permittees, water rights owners, and mining claim owners would take millions of dollars more of the federal budget. Americans would also lose at least 102 square kilometers [39.5 square miles, 25,274 acres] of public lands of undetermined monetary or recreational value to the Fallon Paiute Shoshone Tribe, the Walker River Paiute Tribe, Churchill County, Fallon, and Lander County. The land exchange with Churchill County and other land exchanges may or may not result in a loss of value to the American public. Those costs and losses would not have been necessary if the Fallon Range Training Complex had been moved to another bombing range or to a new range. Other alternatives would have their own unique costs but the Navy didn’t bother to look. At a minimum, Title XXIX demonstrates how inadequate the Navy’s plan and EIS were.

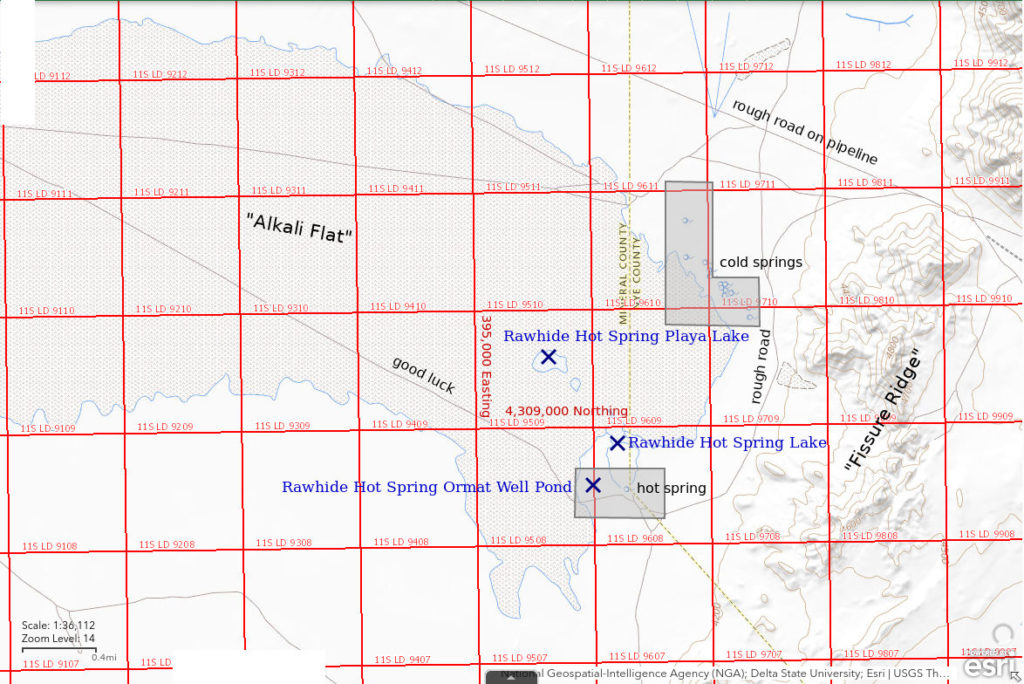

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake (Stillwater BLM Office)

___This map is a screenshot of The National Map (Go to The National Map). The U.S. Geological Survey generally does not copyright or charge for its data or reports (unless printed). A pond location is indicated by an “X”, which corresponds to the coordinates given in the data spreadsheet. Labels in quotations are from 7.5-minute topographic quadrangles.

___Red lines are the U. S. National Grid with a spacing of 1,000 m and intersection labels consisting of the UTM zone (e.g., 11S, 12T), a 2-letter 100-km square designation (e.g., LC, XN), and a 4-digit number. The first 2 digits of the number represent the 1,000-meter Easting and the second 2 digits the 1,000-meter Northing, as seen in the example Easting and Northing. Unlike latitude and longitude, the National Grid is rectilinear on a flat map, the units of abscissa and ordinate have equal lengths, and the units (meters) are measurable on the ground with a tape or by pacing.

___Gray shading represents private land as traced from the PAD-US 2.0 – Federal Fee Managers layer of The National Map. Other lands are public.

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is 57 km (35 miles) northeast of Hawthorne. It is a 200 m by 300 m (660-980′) “intermittent lake” in the northeastern corner of western Gabbs Valley according to the 1:100,000-scale BLM map. The playa here is mostly a salt marsh, like Rhodes Salt Marsh and Teels Marsh. It has very irregular, mineral-encrusted, grayish-brown, popcorn soil with 1-3 m wide polygonal patterns locally. However, within this area of crusty soil, there is a white, non-crusty, smooth-floored basin a few hundred meters across. This is Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake.

Roads to Rawhide Hot Spring provide access to the pond, which is about 1,300 m (4,270′) northwest of the spring. From the south, a road to the hot spring turns off the road to the geothermal plant just west of the big ranch but because it goes through private land, I haven’t tried it. A variety of roads which are not accurately represented on the 1:100,000-scale BLM map extend from the well-maintained road on the west side of the valley around the north side of the valley to the gap between Fissure Ridge and the Monte Cristo Mountains. These include a road along a natural gas pipeline, which is in reasonably good shape. The pipeline road may be passable from the Fissure Ridge – Monte Cristo gap all the way to Gabbs but I have not tried that part. There are other roads from the east on the BLM map. A road leads to the hot spring from the gas pipeline. All of the roads in the area could become impassable due to deep sand or mud, depending on wetness and location. Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is 2,000 m (6,560′) west of a road from the pipeline to Rawhide Hot Spring.

This pond will no longer be accessible once the Navy’s expanded B-17 bombing range is closed to the public.

Elevation: 1,255 m (4,120′)

May 25, 2021

“Cold Springs” at the east edge of “Alkali Flat” on the 1:100,000-scale BLM map raised my hopes for cold spring ponds like those in Smith Creek Valley. There are marshy areas at the springs but no ponds. I walked out onto the dry playa from there and eventually stumbled into the white, smooth-floored basin of Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake. Its floor was much easier and quieter walking. The playa was dry but could be a good place to look for a pond after a snowy winter, abundant spring rains, or a big thunderstorm.

- Dry.

View west across western Gabbs Valley toward Pilot Cone in the Gabbs Valley Range on the horizon at left. Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is the white area above the right end of the green area at right. Most of the playa at this end of “Alkali Flat” has a grayish-brown color indicative of mineral-encrusted soil. Rawhide Hot Spring is in the green area at left. Rawhide Hot Spring Lake is adjacent to the upper right end of the green area at right but is about the same color as the pale gray basin floor next to it.

August 8, 2022

Thunderstorms have been active, off and on, across most of Nevada over the past 3 weeks. Maybe there has been enough rain for water to collect on western Gabbs Valley playa.

- Dry.

The playa is quite dry and crunchy. There is clear evidence of water flowing along and across roads in some places on the approach to Gabbs Valley but the storms weren’t enough for Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake.

Rawhide Hot Spring Lake (Stillwater BLM Office)

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake map

Rawhide Hot Spring Lake is a “perennial lake” feature on the 1:100,000-scale BLM map about 500 m (1,640′) north of Rawhide Hot Spring. On The National Map, it is about 300 m (980′) long and up to 175 m (570′) wide. The lake is also shown as perennial on the Mount Annie 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle. The general appearance and steady (at least in May) stream inflow support that interpretation but the lake is dry on the USGS imagery for The National Map. Rawhide Hot Spring Lake is on public land north of the 80 or so acres (32 hectares) of private land at Rawhide Hot Spring. The private land is not fenced or signed.

The presence of a purported perennial lake at the edge of the playa in western Gabbs Valley requires an explanation. A small stream of cool water flows into the lake from the east. The stream does not connect to the cluster of cold springs to the northeast. Water takes a circuitous route from Rawhide Hot Spring to a boggy area northeast of the hot spring. The stream to the lake issues from this boggy area and so is apparently sourced from the hot spring. It is also possible that there is a cold spring among the reeds that contributes to the flow from the hot spring.

For access, see see Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake.

This pond will no longer be accessible once the Navy’s expanded B-17 bombing range is closed to the public.

Elevation: 1,256 m (4,120′)

May 25, 2021

There really is a lake here. There is cool water flowing into the lake from the east. The avocets are sweeping their bills back and forth through the water and the phalaropes are spinning in circles on the water surface. Maybe they are eating fairy shrimp.

- 150 m x 300 m; depth greater than 20 cm.

- Water murky brown.

- No fairy shrimp.

- Common backswimmers (sub-order Heteroptera, family Notonectidae) less than 8 mm long, very small red swimming spheres that may be water mites, locally numerous gray swimming specks less than 1 mm long may be copepods several avocets, a few Wilson’s phalaropes, a flock of what could be white-faced ibis, killdeer, 1 duck-like bird.

Looking southwest across the east end of the western portion of Gabbs Valley with Rawhide Hot Spring Lake in middle distance to right of center. The lake is the thin strip of blue to the right of the green area. The hot spring is located at the leftmost cluster of trees at the left edge of the green area. The dark object on the far side of the basin above the right-most cluster of trees is the geothermal plant. Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is off the right edge of the photograph. The road from the gas pipeline to Rawhide Hot Spring is in the foreground. The Gabbs Valley Range is in the distance and Mt. Grant is the snow-covered peak on the horizon.

Rawhide Hot Spring Lake, with rushes along the southern shore and Fissure Ridge in the distance to the east. The 2 wakes in the water are from avocets walking toward the left with their heads in the water. There is a third stationary avocet to their left.

August 8, 2022

Although a dry Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake at this time of year was not surprising, it will be interesting to see who the summer inhabitants of Rawhide Hot Spring Lake are.

- Dry.

Looking southeast across a dry Rawhide Hot Spring Lake. The hot spring is to the left of the trees at right and the bog north of the hot spring is the green area at left. The green grass in the foreground would have been on the northwestern shore of the lake before it started drying up. Fissure Ridge is in the background.

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is not perennial after all. Water is still flowing from the hot spring so why has the lake dried up? Could there be seasonal variations in the flow from the hot spring? Are there other contributors to the lake, such as winter/spring groundwater flow to the bog, that have decreased or dried up?

It’s possible that evaporation alone made the lake disappear. The average July pan evaporation rate (for more on evaporation see “Pond Duration” on the About page) at Fallon Experimental Station is 8.0 mm/day while that at Lahontan Reservoir is 11.3 mm/day (0.31-.44 inches/day). Both stations are less than 100 km (60 miles) to the northwest. Assuming Rawhide Hot Spring Lake started July as an ellipse with radii 75 m and 150 m (245′ x 490′), as on May 25, 2021, its area was 35,340 square meters (380,260 square feet). A volume of 283 (Fallon rate) or 400 (Lahontan rate) cubic meters (9,995 or 14,128 cubic feet; 74,770 or 105,680 gallons) could evaporate from a pond of that size every day, on average, through July, if the decrease in evaporation due to the decrease in area as the pond evaporates is neglected. 283-400 cubic meters per day (52-73 gallons/minute) is the same order of magnitude as the flow into Rawhide Hot Spring Lake observed in May 2021. The stream flowing into the lake then was more than a garden hose but much less than a fire hose. Given the uncertainties of pond size and depth, evaporation rates, and spring flow rates, the possibility that evaporation alone was sufficient to dry up the lake this year cannot be ruled out.

The Mount Annie 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle, which shows the lake as perennial, was based on 1974 aerial photographs. Maybe evaporation or spring flow rates have changed in the past 48 years. A seasonal lake is more prospective for fairy shrimp than a perennial lake but I haven’t found any fairy shrimp. Is the colonization process just slow or is there something else keeping them out?

Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond (private)

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake map

Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond is a couple hundred meters (few hundred feet) west of Rawhide Hot Spring. It is a sump, or mud pit, about 10 m (33′) wide, about 55 m (180′) long, and about 1.5 m (5′) deep. This is the maximum size of the pond. There is a big pile of white dirt next to the pond, which is visible from a distance. As natural flow into the sump is negligible, water for the pond is from precipitation.

Sumps are used to control drilling fluids. There is a capped geothermal well nearby that was constructed by Ormat according to the plaque on the well. Ormat operates the Don Campbell geothermal plant about 15 km (9 miles) to the southwest. Sumps are usually back-filled soon after completion of well construction. This sump is on private land and the landowner may not care.

The sump provides a serendipitous experiment in how long it takes fairy shrimp to colonize new habitat, assuming Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond is suitable habitat. Ormat Technologies, Inc., conducted geothermal exploration in the Gabbs Valley area in 2007-2011 and began construction of the Don Campbell Geothermal Plant in 2013 (Orenstein and Delwiche 2014, see the References page). Consequently, it is likely that the pond has existed as potential fairy shrimp habitat since 2011 and possibly since as early as 2007. A “Permitted Geothermal Well” shown at Rawhide Hot Spring on the 2010 map of Nevada Geothermal Resources (Penfield and others, 2010) indicates a pre-2010 construction date. It has been 11 years since 2010 and no fairy shrimp. Although the sump could be back-filled and reclaimed at any time, if that hasn’t happened in over 10 years, it may never happen.

For access to the Ormat Well Pond, see Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake. The road to the well from the hot spring has been built up with gravel as has the large well pad. There are no gates but the hot spring and geothermal well are on private land.

This pond will no longer be accessible once the Navy’s expanded B-17 bombing range is closed to the public.

Elevation: 1,256 m (4,120′)

May 25, 2021

The dirt pile is visible from far away. A dirt pile suggests a hole nearby. Could there be a pond in the hole? I am surprised to find water though. Maybe the water is from the May 21 storm in western Nevada but 15 cm seems a bit deep to have come from one storm.

- About 10 m x about 40 m; depth less than 15 cm.

- Murky pale brown water.

- No fairy shrimp.

- Long wriggly larvae, flies, 1 avocet poking around.

Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond, looking east toward Fissure Ridge. The hot spring is on the far side of the vegetation in the distance. The pit has probably been here since 2007-2010 but there are no fairy shrimp yet (based on this one visit). If the water is from the May 21 storm, any fairy shrimp that hatched wouldn’t be big enough to see yet.

What Can We Learn from the Ponds in Gabbs Valley?

No fairy shrimp have been found in western Gabbs Valley but potential habitat is present. No ponds have been visited in eastern Gabbs Valley.

There is a large, spring-fed lake, Rawhide Hot Spring Lake, in western Gabbs Valley. It is visited by dispersal agents such as avocets and other birds and dries up by August in some years.

Rawhide Hot Spring Playa Lake is a clay-floored flat amid the salt-encrusted soil of most of western Gabbs Valley. It looks like it fills with water at times and could receive overflow from Rawhide Hot Spring Lake.

Rawhide Hot Spring Ormat Well Pond provides an ongoing experiment in fairy shrimp colonization. The pond was dug as the sump for a geothermal exploration well at some time during the period 2007-2010.

Ponds suitable for fairy shrimp do not occur near the cold springs in the northeastern part of western Gabbs Valley.

The northeastern part of western Gabbs Valley and all but the southeastern part of eastern Gabbs Valley will be closed to the public as a result of expansion of the Navy’s B-17 bombing range, probably by the end of 2029.