The base map is provided by OpenTopoMap’s volunteer servers.

Previous Reports of Fairy Shrimp in the Sierra Nevada

Glaciation of the Sierra Nevada

Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

___ What Is Fish-stocking?

___ Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

___ Why Is Fish-stocking Important to Fairy Shrimp?

___ How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

___ How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Sierra Nevada?

___ What is the Experimental Evidence of the Effects of Fish-stocking

___ What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Invertebrates in the Sierra Nevada?

___ What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been Beyond the Sierra Nevada?

___ What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Vertebrates?

___ Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Virginia Divide Double Ponds

Virginia Creek Pale Green Pond

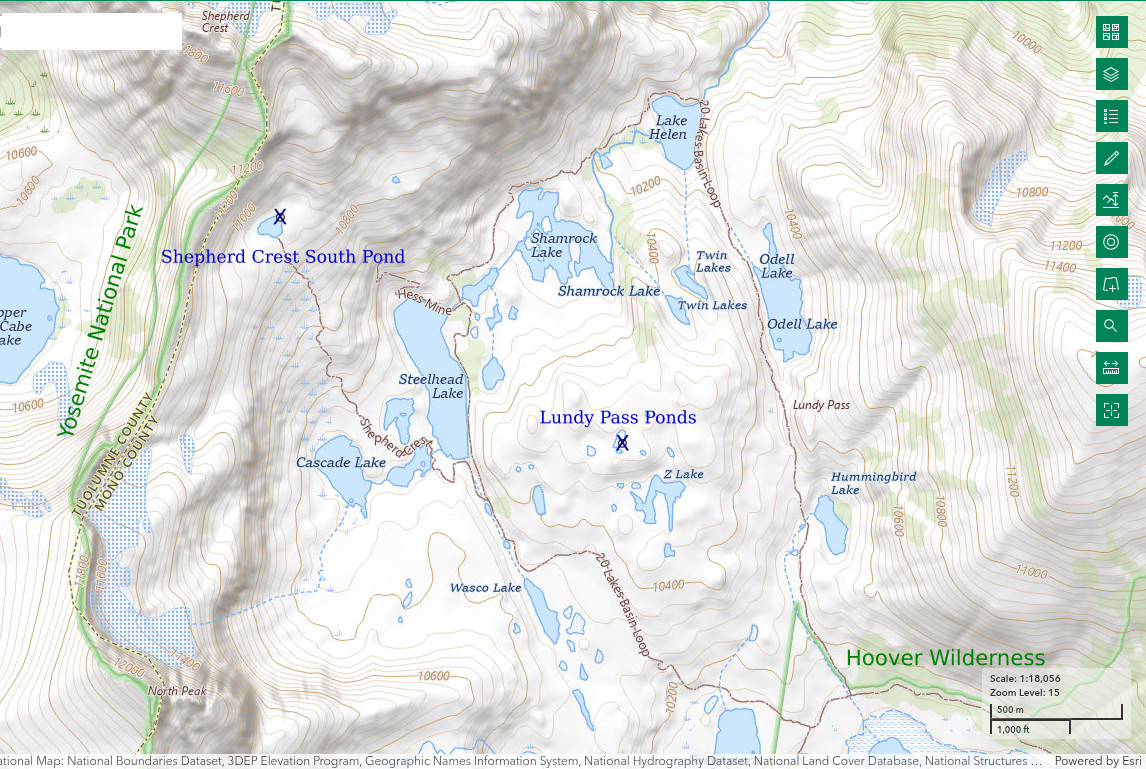

Lundy Pass Ponds

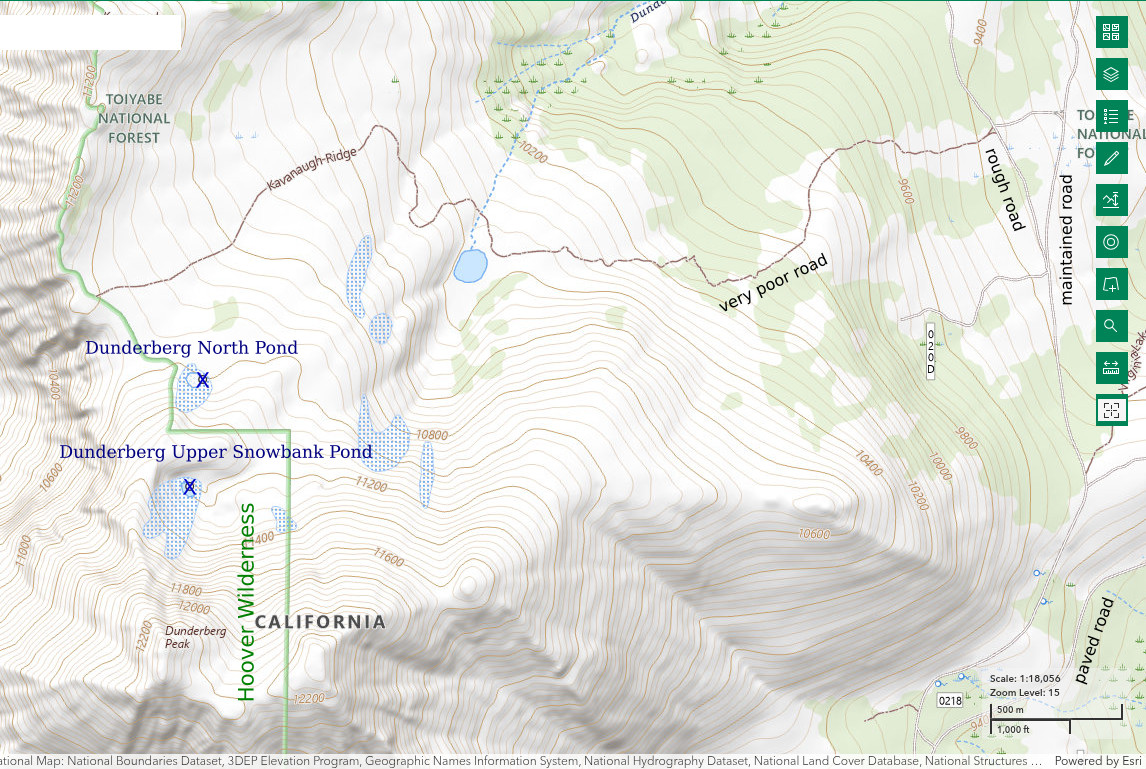

Dunderberg North Pond

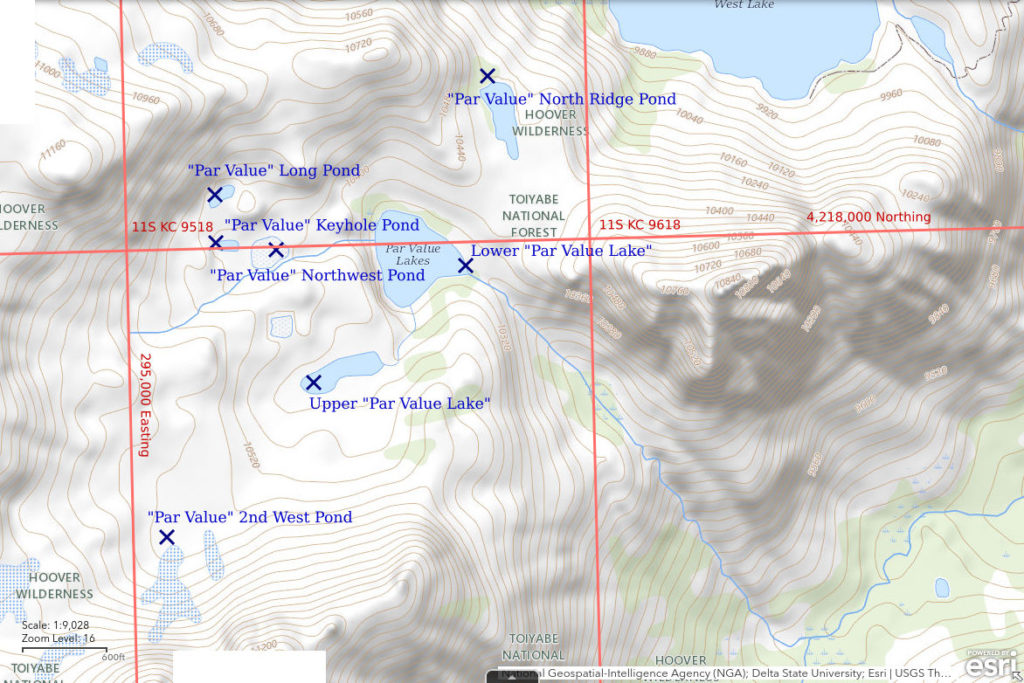

Lower “Par Value Lake”

Upper “Par Value Lake”

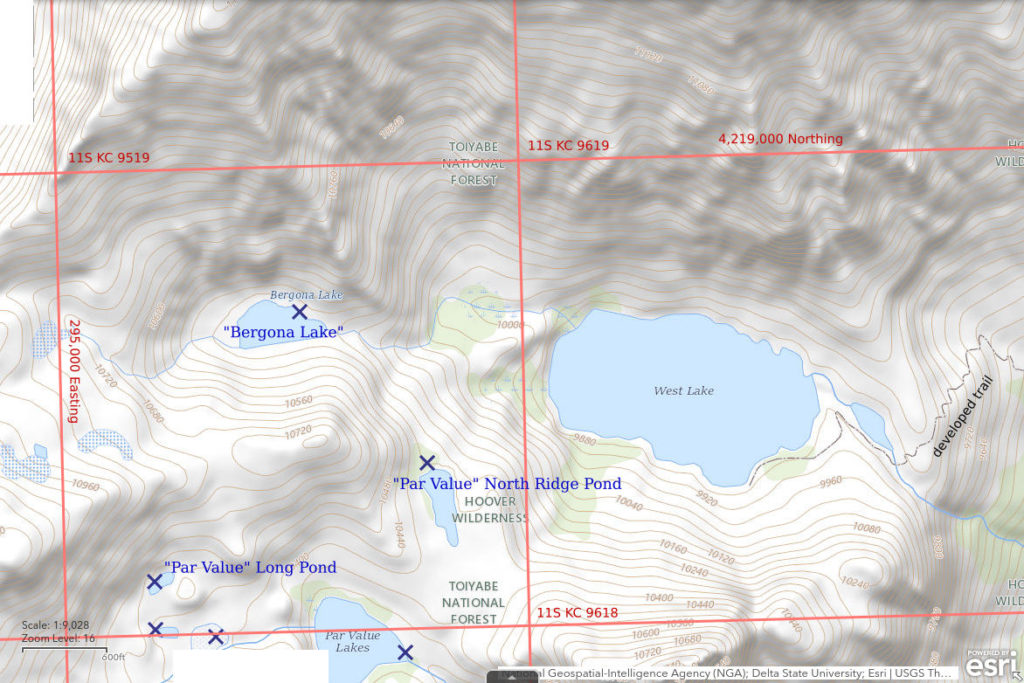

“Par Value” 2nd West Pond

“Par Value” Long Pond

“Par Value” Keyhole Pond

“Par Value” Northwest Pond

“Par Value” North Ridge Pond

“Bergona Lake”

“Burro Lake”

Burro Cirque Pond

Shepherd Crest South Pond

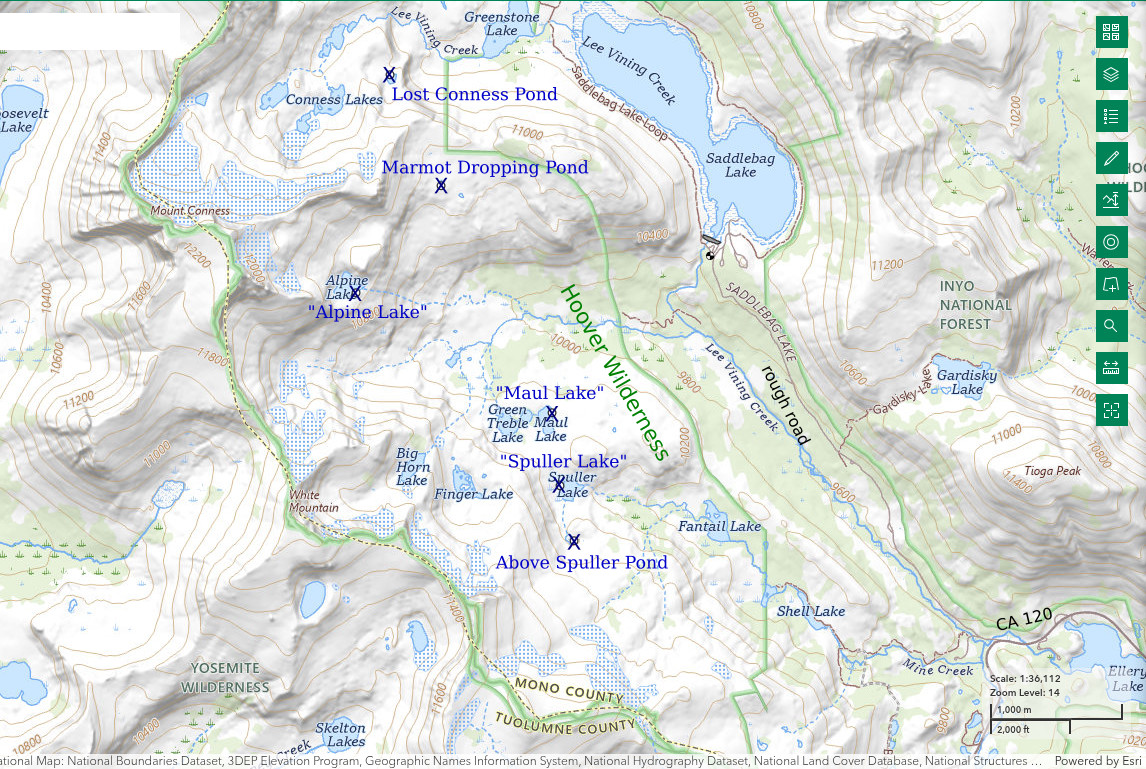

“Maul Lake”

“Spuller Lake”

Above Spuller Pond

Marmot Dropping Pond

“Alpine Lake”

Lost Conness Pond

Dunderberg Upper Snowbank Pond

What Can We Learn from the Ponds in the East-Central Sierra Nevada?

I have looked for fairy shrimp in only a small part of the Sierra Nevada between highways 108 (over Sonora Pass) and 120 (over Tioga Pass) and east of the crest of the range. The distance between Sonora and Tioga passes is only about 56 km (35 miles). To avoid giving the impression that I have visited ponds throughout the range, I use the term East-Central Sierra Nevada but this term could well encompass a larger area in many people’s minds. The Sierra Nevada is much steeper on the east side than the west side so the area east of the crest is much smaller than the area to the west. For example, it is about 12 km (7.5 miles) from Lee Vining to Tioga Pass but another 48 km (30 miles) to El Portal.

Where I have hiked in the East-Central Sierra Nevada, elevations range from about 2,250 m (7,380′) on the eastern flank to highs of around 3,150 m (10,330′) along the crest (e.g., at “Summit Lake”). The peaks, of course, are higher. Mt. Warren is 3,757 m (12,330′), Dunderberg Peak is 3,772 m (12,370′), and Matterhorn Peak is 3,738 m (12,260′).

Vegetation in the East-Central Sierra Nevada includes sagebrush, pine, aspen, fir, and alpine tundra. I don’t know many of the species.

The Sierra Nevada are a recreational wonderland due in large part to the nearly complete coverage by public lands managed by the National Park Service or by the U.S. Forest Service. However, there are private in-holdings along many of the access roads and the Marine Corps Mountain Warfare Training Center east of Sonora Pass should also be avoided. There are many reasonably well-maintained hiking trails in the east-central Sierra Nevada. The trailheads are accessible on bumpy roads from US 395 to the east, California 108 to the north, and California 120 to the south. The towns of Bridgeport and Lee Vining are nearby on US 395.

East-Central Sierra Nevada – top

Previous Reports of Fairy Shrimp in the Sierra Nevada

3 species of fairy shrimp were recorded in the Sierra Lakes Inventory Project (Knapp and others, 2020): Branchinecta coloradensis, Branchinecta oriena, and Streptocephalus seali. The survey has a few records of “Branchinecta sp.”, where only the genus was identified. Eng, Belk, and Eriksen (1990) listed 2 occurrences of Branchinecta coloradensis in the Sierra Nevada at elevations of 3,050 m (10,010′) and 3,500 m (11,480′), 9 occurrences of Branchinecta dissimilis between Lake Tahoe and Bishop at elevations of 2,440-3,506 m (8,010-11,500′), and 35 occurrences of Streptocephalus seali in coniferous forest from Lassen Volcanic National Park to Mammoth Mountain at elevations of 2,100-3,032 m (6,890-9,950). The Branchinecta dissimilis occurrences may include the 2 of Stoddard (1987). Some of the fairy shrimp identified as B. dissimilis may have been misidentified B. oriena (Belk and Rogers, 2002, abstract only).

There are no doubt reports by others of fairy shrimp in the Sierra Nevada but I haven’t found them online.

How common fairy shrimp are in the Sierra Nevada has not been well determined.

Stoddard (1987) found fairy shrimp in 2 of 17 fishless lakes, or 12%. Stoddard (1987) claimed his 75-lake sample was “representative of the geological and ecological diversity of the Sierra Nevada”. Surface areas ranged from 0.3 to 578 hectares (0.7-1,430 acres) and depths from 0.5 to 90 m (1.6-295′). Elevations ranged from 1,900 m to higher than 3,000 m (6,230 to >9,840′).

Bradford and others (1998) didn’t see fairy shrimp in the 18 fishless lakes they surveyed. This implies an occurrence rate of less than 5.5%. Bradford and others’ (1998) 33 surveyed lakes were in Kings Canyon National Park. They had areas of 0.12 to 30.5 hectares (0.3-75 acres), depths of 0.3 to 10.0 m (1-33′), and elevations of 3,130 to 3,672 m (10,270-12,050′).

In Lassen Volcanic National Park in the northern Sierra Nevada, the fairy shrimp Streptocephalus sealii [sic?] occurred in 1 of 32 fishless lakes, for an occurrence rate of 3.1% (Parker, 2008).

The Sierra Lakes Inventory Project (Knapp and others, 2020; database available online at doi.org/10.6073/pasta/d835832d7fd00d9e4466e44eea87fab3) surveyed 7,863 lakes in Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia National Parks and the John Muir Wilderness in the central and southern Sierra Nevada. The survey was designed to detect the presence of amphibians and fish but also collected zooplankton samples with vertical tows of a plankton net (not effective for fairy shrimp) and benthic macroinvertebrates. Surveyors were also instructed to “be on the look out for schools of fairy shrimp”. Fairy shrimp were found at 258 locations (3.6% of fishless lakes). However, 16 of the fairy shrimp locations had fish. It is more likely that for these locations, the fairy shrimp were found in ponds near lakes with fish rather than in the same water body. The survey protocol called for recording fairy shrimp if they are in “lake-associated pools” within 2 m of the lake or in “other locations”. The Sierra Lakes Inventory Project survey is strongly biased toward large lakes. Only 1% of the lakes were smaller than 36 hectares (89 acres).

The above surveys indicate fairy shrimp aren’t common in fishless lakes of the Sierra Nevada. They are half as common in all lakes given that more than 60% of lakes there have fish (Knapp and Marine Science Institute, 1996). Too few fairy shrimp populations have been found (i.e., less than 300) and described (i.e., none) to say with any confidence where the best places to look are.

East-Central Sierra Nevada – top

Glaciation of the Sierra Nevada

The Sierra Nevada is famous for its glacial features, such as those in Yosemite National Park. In addition to the cliff-bordered glacial valleys, the crest of the range is often a sharp ridge with horns, such as Matterhorn Peak. Broad valleys such as the upper part of Virginia Creek valley are obviously good for lakes and ponds. The Sierra Nevada also has uplands with moderate, rolling topography that are also good for ponds. One example is the upland from Lundy Pass to California 120 along the west side of “Saddlebag Lake”. Unlike the Wind River Mountains, where cirques with lakes are not uncommon (e.g., Silas Headwall Lake, Upper “Ice Lakes” First Lake, and North Tayo Cirque Upper Pond), cirques along the crest of the Sierra Nevada are small and may have snow fields but generally lack lakes (e.g., the cirque above Shepherd Crest South Pond and the cirque south of Virginia Creek Pale Green Pond). Instead, features that have high, arcuate cliffs above lakes are generally well below the crest of the range. Examples are “Alpine Lake” and the hanging valley of “Bergona Lake”).

All the higher elevation ponds and lakes of the Sierra Nevada were covered by glaciers of an extensive ice cap by the end of the last glacial advance about 25,000 years ago (Fig. 1 of Rood and others, 2011; Fig. 2 of Phillips, 2017). The maximum extent of ice is marked by so-called Tioga (or Tioga 3, as in Phillips and others, 2009) moraines. Moraines are piles of rock that accumulate at the fronts and along the margins of glaciers. Although Tioga moraines are generally in deep valleys among the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, they imply that ice also covered the higher elevations. Consequently, there was no fairy shrimp habitat until the glaciers melted back from the Tioga moraines. The timing of ice melting can be determined using radioactive isotopes that are formed when cosmic rays impinge on various elements such as silicon, oxygen, aluminum, potassium, calcium, and carbon in rock minerals. Samples for such dating are collected from moraine boulders and from polished bedrock that was also covered by ice. For more on moraines and their exposure ages, see “Glaciation of the Wind River Mountains” on the Wind River Mountains page.

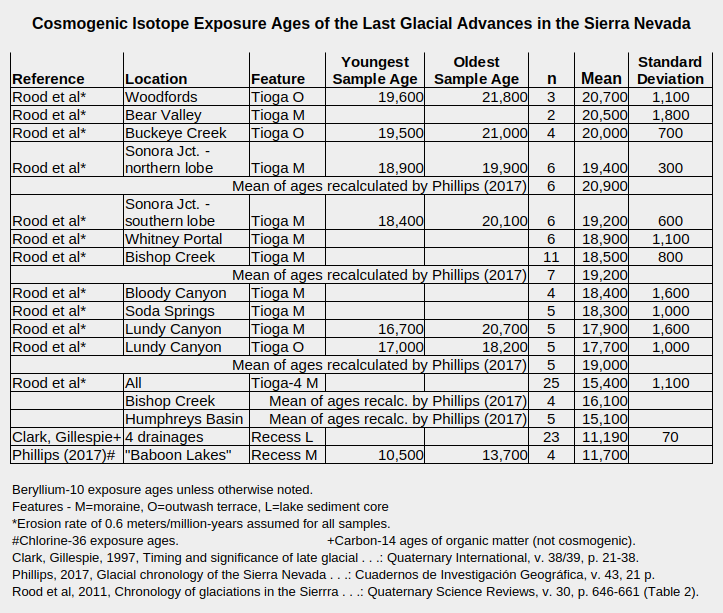

Rood and others (2011) have compiled exposure ages for Tioga moraines at several locations in the Sierra Nevada and have recalculated the ages with updated isotope half lives, production rates, and scaling factors. This makes the ages from different studies comparable. Phillips (2017) also presented recalculated ages for some of the same studies used by Rood and others (2011). These exposure ages are summarized in the table of Cosmogenic Isotope Exposure Ages of the Last Glacial Advances in the Sierra Nevada below. Phillips’s (2017) newer recalculated ages for the northern lobe of the Tioga moraine at Sonora Junction, the Tioga moraine at Bishop Creek, and the Tioga outwash terrace at Lundy Canyon are 1,500, 700, and 1,300 years older, respectively, than those of Rood and others (2011). Other ages presented by Rood and others (2011) would probably also be older by the same magnitude if recalculated using the parameters of Phillips (2017). Rood and others (2011) calculated the mean of all the Tioga 4 ages determined by Phillips and others (2009) but Phillips (2017) broke these out into 2 geographically specific ages that he considered more meaningful.

Paraphrasing the conclusions of Phillips (2017) to summarize the timing of the most recent major glacial activity in the Sierra Nevada, the Tioga glaciers reached their maximum extent by about 21,000 years ago. By 18,000 years ago, they had begun to retreat. The retreat continued at least as far up valley as where the Tioga 4 moraines were subsequently deposited. Figure 2 of Phillips (2017) shows that Tioga 4 moraines in Bishop Creek, Rock Creek, and South Fork San Joaquin River valleys were approximately 7.5 km, 7.0 km, and 12.4 km (4.5, 4.2, 7.4 miles) up valley from the Tioga 3 moraines, respectively (as measured from the figure by me). Other authors haven’t distinguished Tioga 3 and Tioga 4 moraines and have considered the moraine farthest down valley as simply Tioga. The Tioga 4 moraines were deposited by 16,200 years ago (Phillips, 2017). The glaciers then melted relatively quickly and had withdrawn to the crest of the Sierra Nevada by 15,500 years ago. Although this age choice is older than the 15,100 years mean age for Humphreys Basin, it is within the standard deviations of single boulder ages, which are 1,200-1,600 years (Phillips, 2017). By 14,000 years ago, glaciers began to form again and advanced a short distance from the crest of the Range. The Recess Peak moraines had been deposited by 12,000 years ago (i.e., “Baboon Lakes” age rounded to 2 significant figures). The glaciers then retreated rapidly “to positions that were probably less extensive than historical glaciers” in the Sierra Nevada (Phillips, 2017).

East-Central Sierra Nevada – top

What does this chronology mean for potential fairy shrimp habitat? 18,000 years ago there was none in most of the Sierra Nevada. Although a few Tioga 4 moraines have been identified in major valleys, the extent of glaciers at higher elevations has not been addressed. My guess is that the Tioga 4 advance didn’t cover lower elevation lakes (that now have fish), such as “Twin Lakes”, southwest of Bridgeport; “Green Lake”, southeast of “Twin Lakes”; and the “Virginia Lakes”, southeast of “Green Lake”. It may well have covered higher elevation areas, such as “Par Value Lakes” and nearby fishless ponds, above “Green Lake”; the hanging valley with “Burro Lake” and the fishless Burro Cirque Pond, above Lundy Canyon; and the Lundy Pass area, south of Lundy Canyon. Because the ponds least likely to have been stocked with fish are mostly small and at relatively high elevations, much, if not most, of currently available fairy shrimp habitat would have been frozen in until 16,200 years ago.

A Little Ice Age advance during the period 1300 to 1850 has been widely inferred, particularly by geomorphologists, but absolute dates in the Sierra Nevada are few. Beryllium-10 exposure ages of 100-400 years ago from boulders of moraines below East Lyell, West Lyell, and Conness glaciers support this interpretation (Jones and others, 2025). Boulders with ages older than 800 years on moraines below Maclure and Palisade glaciers do not. Assuming no inheritance, Jones and others (2025) determined mean exposure ages of 1,700 years (n=4) and 3,400 years (n=4) for inner and outer moraine ridges at Maclure and 1,000 years (n=6), 2,100 years (n=5), and 1,500 years (n=6) for the inner, middle, and outer moraine ridges at Palisade. Consequently, the Maclure and Palisade moraines formed well before the Little Ice Age, possibly during multiple asynchronous glacial advances.

However, at no time since 12,000 years ago did the glaciers get far from the crest of the Sierra Nevada. The detailed maps of Jones and others (2025, Fig. 3) show that the moraines they dated are quite close to the 2013 ice margins of historical glaciers, i.e., about 125 m (410′) at Conness Glacier, 140 m (460′) at West Lyell Glacier, 275 m (900′) at Maclure Glacier, and 350 m (1,150′) at East Lyell, which is almost gone. Of these 4, the longest post-Recess Peak glacier would have been Maclure, at about 525 m (1,720′). I couldn’t determine the distance from the ice margin of Palisade Glacier to its moraine but the total length is about 1,250 m (4,100′). Given the short glacier lengths and the steep slopes above the most recent moraines, these post-Recess Peak advances had negligible impacts on the availability of fairy shrimp habitat. Figure 3 of Jones and others (2025) shows small ponds below the moraines at West Lyell, Maclure, and Conness but only Palisade has a pond above its moraine.

How far did the Recess Peak glaciers get by 12,000 years ago? Jones and others (2025) stated, “The Recess Peak advance occupied roughly twice the area of the Matthes advance”. As summarized in the previous paragraph, Matthes advances were generally less than 1 km (0.6 mile). That suggests that the Recess Peak glaciers also had minimal impacts on available fairy shrimp habitat and that the key date is 16,200 years ago for the maximum of the Tioga 4 advance. Figure 3 of Jones and others (2025) shows that the uppermost of the “Conness Lakes” wouldn’t have been covered if the Conness Glacier doubled in size from its Little Ice Age moraine but that a small pond at the base of the ridge north of Conness Peak would have been. Judging from the 7.5-minute topographic maps I have used for the east-central Sierra Nevada (i.e., Dunderberg Peak and Tioga Pass), “Bergona Lake”, the “Par Value Lakes”, Virginia Divide Double Ponds, Burro Cirque Pond, Lost Conness Pond, “Alpine Lake”, and Above Spuller Pond would not have been affected by Recess Peak glaciation. Shepherd Crest South Pond would not have been buried with ice if the moraine in the cirque above it is Recess Peak. If that moraine is younger than Recess Peak, the pond could have covered by the Recess Peak advance. Because Dunderberg North Pond and Dunderberg Upper Snowbank Pond are both adjacent to perennial snowbanks, expansion of those snowbanks during the Little Ice Age advance would have buried the ponds.

I have 1 photograph that illustrates a pond that was close to, but was not covered by the Recess Peak advance, I think. Burro Cirque Pond lies on moraine material at the base of a steep slope below a higher cirque. It lies on a broad hummocky area of boulders and smaller glacial debris that extends almost 600 m (1,970′) from the base of the steep slope southwest of the pond to almost half the way to “Burro Lake”. This material has subterranean drainage between the boulders rather than surface streams. The debris becomes discontinuous down valley and is not bounded by a terminal moraine ridge. The 7.5-minute topographic map shows a perennial snowbank adjacent to the cliffs of the cirque but no pond. It is 540 m (1,770′) from the top of the snowbank to the lip of the cirque on the map. The snowbank itself was only about 250 m (820′) long in 1985, when the aerial photograph for the map was shot. To me, the most plausible explanation is that the 1985 snowbank occupies almost all of any post-Recess Peak ice extent (e.g., Little Ice Age) and that the Recess Peak advance stopped before the glacier got to Burro Cirque Pond. The rubble at the cirque lip could be Recess Peak-age moraine. There are 2 small ridges of boulders a little more than halfway down the steep slope to Burro Cirque Pond. They could mark the lowest extent of any Recess Peak moraine. The distances satisfy the Jones and others (2025) criterion of Recess Peak ice being twice the area of post-Recess Peak ice. The steep slope between the upper cirque and Burro Cirque Pond could have been carved by either a Tioga or Tioga 4 glacier. The moraine from the base of the steep slope down the valley is best explained as a recessional moraine of Tioga 4 age. If it had been deposited by a Tioga glacier, then the upper cirque could be Tioga 4 age and there would be no place to squeeze in Recess Peak ice. This analysis allows me to claim that fairy shrimp have had no more than 16,200 years to colonize Burro Cirque Pond. Allowing 1,000 years for Tioga 4 retreat gives them 15,200 years. Their absence from Burro Cirque Pond and from all the other ponds I have visited in the east-central Sierra Nevada indicates that fairy shrimp colonization has been hampered in this area by something other than time.

View to the southwest at Burro Cirque Pond showing the steep slope above it and the lip of a higher cirque at upper right. For another view of the pond, see Burro Cirque Pond 2021 #29.

East-Central Sierra Nevada – top

Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What Is Fish-stocking?

Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

Why Is Fish-stocking Important to Fairy Shrimp?

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Sierra Nevada?

What is the Experimental Evidence of the Effects of Fish-stocking

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Invertebrates in the Sierra Nevada?

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been Beyond the Sierra Nevada?

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Vertebrates?

Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What Is Fish-stocking?

Fish-stocking is the dropping of 1 or more live fish into a body of water. Fish management agencies typically dump a couple hundred to a few thousand, small (7-18 cm, 2-7″) fish at a time into a mountain lake from a helicopter. The dumped fish are species that people like catching and are usually obtained from a state-supported fish hatchery. They are exotic to the receiving lake unless the fish management agency is trying to restore a native species that was wiped out by exotic fish. Larger fish that don’t need to grow as much before they become “catchable” are dumped in some cases. Most mountain lakes that are currently being stocked in the western United States are stocked repeatedly on periodic (e.g., every 2-4 years) or irregular schedules because the fish populations don’t reproduce. Individuals have also stocked lakes on their own initiative using the means at their disposal. Before helicopters, this included packing large cans of water with fish on horses. Individuals have also dumped bait fish, such as minnows, into lakes rather than carry them home or back to their water body of origin.

The effects of fish-stocking extend beyond the lakes where the fish were dropped. If one lake in a basin with several lakes above the fish-blocking topography were stocked, the fish would move to adjacent lakes through connecting streams to the extent possible. Those lakes could also be considered “stocked”.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Why Is Fish-stocking Needed?

Most of the high mountain lakes and ponds in the Sierra Nevada are above topographic barriers like waterfalls or rapids that prevent natural access by fish. Some people get bored in the mountains and want something to do other than climbing, hiking around, or just admiring the scenery and natural plants and animals. Fishing gives them something else to do. For that to be possible, somebody has to put fish in the mountain lakes. If the introduced fish population doesn’t reproduce, then the lakes have to be stocked again.

Additionally, fishing is a well regarded recreational activity that is good for advertising. State and local governments and businesses in towns near the mountains can use photos of lakes and the possibility of fishing to attract tourists who may rent rooms, buy meals, buy gas, buy stuff at sporting goods stores, and maybe even hire an outfitter.

To those fishing the mountain lakes, the fish seem free. What better draw than free food? The cost of a fishing license is not connected to the economic or environmental costs of stocking a lake with fish. There is no sign that says that a lake has been stocked. Those fishing at an alpine lake don’t know what animals were there before. Even if they did, they would probably consider large aquatic invertebrates creepy creatures that the lake is better without.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Why Is Fish-stocking Important to Fairy Shrimp?

Fish eat fairy shrimp. The 2 animals have been found in the same body of water in only a very few instances (“Fish Predators” on the Predators of Fairy Shrimp page) and those instances were characterized by very rare conditions. Fish use their visual senses to find prey. Adult fairy shrimp are easily visible. They are not brightly colored but they are large in the context of aquatic invertebrates, generally longer than 10 mm (0.4″). They also swim throughout the daytime as well as nighttime hours. They don’t hide in vegetation as that would interfere with their filter-feeding.

Size preferences of rainbow trout and yellow perch were tested in 2 lakes in Michigan. By collecting zooplankton samples and examining the contents of fish stomachs, Galbraith (1966) found that both species ate larger than average cladocerans of the genus Daphnia (Branchiopoda: order Anomopoda, family Daphniidae). 96% of the Daphnia eaten by trout and 82% of those eaten by perch were longer than 1.3 mm (0.05″) even though 58% of Daphnia in 1 lake and 46% of those in the other were smaller than this. The range of Daphnia sizes was 0.4-2.9 mm (0.016-0.11″). The good news is fish eat animals as small as 1.3 mm and that could mean reduced predation pressure on fairy shrimp. The bad news is those were the biggest prey available and the preference for larger prey could apply across the spectrum of prey sizes.

The fishing industry knows this. I would wager that it doesn’t make lures smaller than 2 mm (0.08″). Many lures have bright colors and reflective surfaces. Many of the millions of people who fished in fresh waters over the past several millennia also knew this.

Other aquatic animals use various strategies to avoid predators. Some cladocerans, which are also branchiopods, migrate down to deep, dark water during the day so predators can’t see them. They return to shallow water at night for feeding on non-migrating algae. I haven’t read of daily vertical migrations by fairy shrimp.

Most amphipod populations survive in the presence of fish. Amphipods are crustaceans, like fairy shrimp, that live in lakes, streams, and oceans. Some species grow to be as big as fairy shrimp. Amphipods have stiff exoskeletons that make them less palatable but that doesn’t stop fish, or ducks, from eating lots of them if they can. Amphipods can recognize predators using chemical cues and use various methods to avoid them but responses differ between species. Pontogammarus robustoides recognizes predators by the presence of its fellow species in their feces (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). Dikerogammarus villosus (DV), a very successful invasive amphipod, recognizes all the fish species it has been tested with, even tropical fish from a different continent (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). In what may be a unique or uncommon adaptation, DV distinguishes between hungry and satiated predators. It avoids the hungry ones but may move toward the satiated ones in anticipation of feeding on fish feces or on the prey the fish is feeding on (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). In contrast, Gammarus minus reduced its swimming activity in the presence of bluegills and striped shiners even though striped shiners didn’t eat the amphipods (Wooster, 1998). I have not read of fairy shrimp detecting fish or other potential predators chemically.

DV uses a few simple strategies to avoid predators. It spends most of its time sheltering on the river or lake bottom (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). If the bottom has good stony (or comparable) shelter, DV stays there more than 80% of its time even in the absence of hungry predators. In other experiments with evidently less appealing shelter, DV reduced its swimming in the water column from 55% of its time to 20% in the presence of predators (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). On a sandy bottom without shelter, DV swims away from a predator rather than seeking shelter. Alternatively, DV forms aggregates on the bottom with other DV when no shelter is available. Due to the stiff exoskeletons and strong clinging abilities of DV, aggregates are hard to eat. Some fish species (e.g., racer goby) avoided aggregated DV and preferred eating singletons (Jermacz and Kobak, 2018). I have not read of fairy shrimp taking refuge in vegetation or rocky pond bottoms and doubt that it would be feasible.

The lack of obvious defense mechanisms may make fairy shrimp seem ecologically incompetent but that is not the case. The order Anostraca has survived for more than 300 million years (Taxonomy and Origin of Anostraca page) not by engaging in a predator-prey arms race but by adapting to ponds where fish can’t survive. This strategy must have been adopted early as there are fish fossils in non-marine sediments as old as the earliest known fairy shrimp ancestors. Fairy shrimp populations aren’t utterly helpless. They seem to co-exist fine with invertebrate predators, such as dytiscids, backswimmers, and amphipods, and with birds. You can find numerous examples in the pond descriptions on this web site. Whether they need, or have, specific defense mechanisms for such co-existence is an open question. If fairy shrimp were ultimately eliminated from all alpine lakes globally due to human recreational preferences, they would carry on as usual in many other fishless environments.

It may be possible for fairy shrimp to survive fish predation if the pond has abundant alternative prey that fish like. In theory, a fairy shrimp population could hatch and produce eggs in a short time before alternate prey is depleted by predation. Maturity would take longer in cold alpine ponds but the fairy shrimp may not have to live all summer long in order for the population to persist. Thus, it is worth looking at the fates of other aquatic animals that have been victimized by fish-stocking. If populations of other large invertebrates can survive fish-stocking, maybe there is hope for fairy shrimp.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Western United States?

A 1988 compilation of estimates supplied by fish and wildlife agencies in the western United States (Colorado and states west) indicated that of approximately 16,000 mountain lakes, 60% (9,600) have fish but less than 5% (800) had fish before fish-stocking began (Bahls, 1992). Even lakes with native fish have been stocked. Fish and wildlife managers thought that only 1% (160) of lakes have only native fish. Larger lakes are more likely to sustain populations of exotic trout. Fish and wildlife managers guessed that less than 5% of lakes larger than 2 hectares (5 acres) and deeper than 3 m (10′) remained free of fish.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

How Extensive Has Fish-stocking Been in the Sierra Nevada?

Fish-stocking in the Sierra Nevada started earlier than in most mountains of the western United States. Gold and silver miners could have started stocking alpine lakes in the Sierra Nevada as early as the 1850s. Native cutthroat trout populations in “Lake Tahoe” were severely depleted to feed the Comstock silver boom near Reno in the 1860s and finally extirpated in the 1930s after relentless predation by stocked lake trout and competition with stocked brown trout and rainbow trout (Truckee River Basin Recovery Implementation Team, 2003). Within the Truckee River watershed upstream of Pyramid Lake, native cutthroat populations have survived only in “Independence Lake”.

Knapp and Marine Science Institute (1996) discussed evidence that the percentage of lakes with fish in the Sierra Nevada above 1,800 m (5,910′) in elevation and greater than 1 hectare (2.5 acres) in area has increased from less than 1% before the mid-1800s to about 63% in the 1990s. This does not include “Lake Tahoe”, the upper Truckee River watershed, or other areas which are outside the inferred fishless area in Figure 2 of Knapp and Marine Science Institute (1996). Of 649 lakes within a California Department of Fish and Game database for Region 5 in the central Sierra Nevada, all were originally fishless but 85% now contain fish (Knapp and Marine Science Institute, 1996). California Department of Fish and Game regularly stocked 46% of the lakes at the time of the report. For better and worse, fish-stocking in the Sierra Nevada has been pervasive.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What is the Experimental Evidence of the Effects of Fish-stocking

Experiments which put fish and fairy shrimp, or other large invertebrates, in the same body of water provide evidence for what would happen when fish are added to a lake with fairy shrimp. The few that I have found are summarized in “Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Wind River Mountains” on the Wind River Mountains page. Trying to extrapolate the results of experiments to the Sierra Nevada is not necessary because several studies have documented the post-fish-stocking faunal differences between stocked and not stocked lakes.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Invertebrates in the Sierra Nevada?

After-the-fact comparisons of fish-stocked and fishless lakes in the Sierra Nevada offer considerable insight into the effects of fish-stocking. Such studies provide correlations between various invertebrate species populations and the presence of fish but are not proof of what fish-stocking actually did. Nevertheless, if similar results are obtained by many studies, then the effects of fish-stocking can be ascertained with high confidence.

Zooplankton in Central and Southern Sierra Nevada:

Copepods (Crustacea: class Maxillopoda, subclass Copepoda)

Cladocerans (Crustacea: class Branchiopoda, orders Anomopoda, Ctenopoda, Onychopoda, Haplopoda)

The relatively large copepods Diaptomus shoshone and Diaptomus eiseni and the cladoceran Daphnia middendorffiana have a strong negative correlation with fish across the 75 lakes in the Sierra Nevada sampled by Stoddard (1987). 58 of those lakes had fish. These species were present in only 8, 7, and 14 lakes, respectively. It’s possible one or more of these species never occurred with fish but Stoddard (1987) did not publish presence-absence data by lake. D. shoshone is commonly 2.5-3.5 mm (0.10-0.14″) long (Wilson, 1953). Conversely, smaller zooplankton such as the cladocerans Daphnia rosea and Bosmina longirostri and the copepod Diaptomus signicauda, were positively correlated with the presence of fish. Their small sizes offer some protection against fish predation and they likely benefited from the absence of large copepod and cladoceran predators. Their presence in fish-hosting lakes further supports a fish preference for large prey.

Chaoborids (Insecta: order Diptera, family Chaoboridae) in Central and Southern Sierra Nevada

The phantom midge, Chaoborus americanus, is usually common in high-elevation lakes but was not found in any of Stoddard’s (1987) 75 lakes. Chaoborid larvae are morphologically similar to mosquito larvae and are 4-20 mm (0.16-0.79″) long (Borkent, 1979, p. 136). Predation by the copepod Diaptomus shoshone could partly explain the absence of C. americanus but the copepod was found in only 8 of the lakes. The highest elevation lakes surveyed may have been too cold for C. americanus but there were only a few of those. The most likely explanation for the absence of C. americanus from Stoddard’s (1987) lakes is that all populations, whether a few or many, were eliminated by fish.

Fairy Shrimp in in Central and Southern Sierra Nevada

2 of the lakes in Stoddard’s (1987) survey had the fairy shrimp Branchinecta dissimilis. Those ponds were small and shallow. Stoddard (1987) grouped zooplankton species into communities and put B. dissimilis in a community with Daphnia middendorffiana and Diaptomus eiseni (see Copepods above). At least 2 of these 3 species occurred in 6 ponds. On average, the 6 ponds had an area of 0.9 hectare (2.2 acres) and a depth of 2.7 m (9′). Standard deviations of only 0.3 hectare (0.7 acres) and 1.3 m (4.3′) suggest none were big. Does that mean the B. dissimilis community was incapable of surviving in larger, deeper lakes? No. I have observed fairy shrimp in ponds that looked deeper than 3 m to me although I couldn’t measure such depths. Area is probably not an issue. A different species of fairy shrimp occurs in relatively large lakes in the Wind River Mountains (e.g., Bivouac Lake, Upper and Lower Indian Pass Lakes, and “Island Lake” Pond #2). Other species occur in large lakes in sagebrush steppe, like “Coyote Lake” and Big “Lewiston Lake”(Antelope Hills). The fact that B. dissimilis was present only in small ponds could mean any populations in larger lakes were eliminated by stocked fish. Small ponds would not have been stocked because they are not suitable for fish or are not of interest to anglers searching for the “big one”.

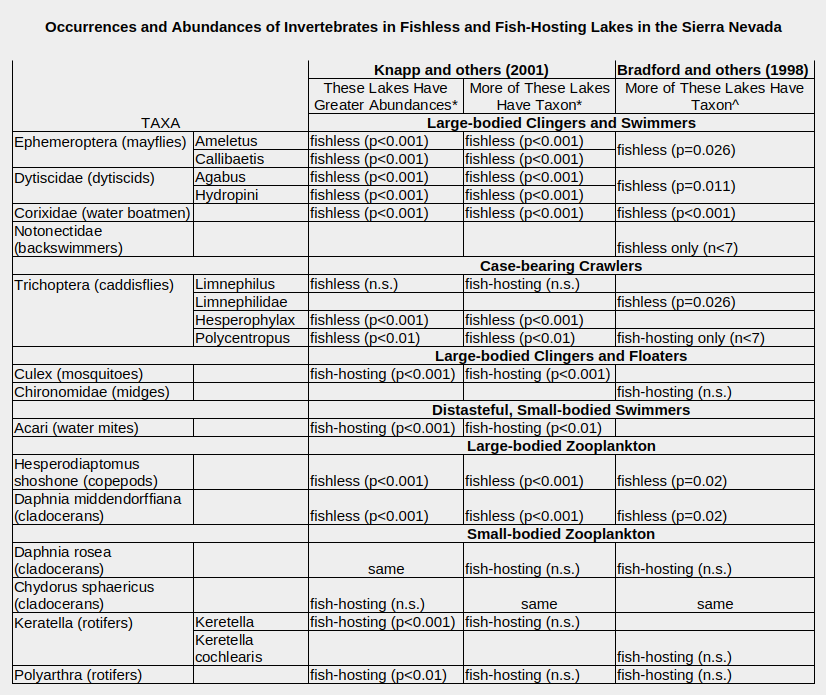

Zooplankton and Benthic Invertebrates in Kings Canyon National Park and John Muir Wilderness

Bradford and others (1998) and Knapp and others (2001) considerably extended the comparisons of large invertebrates in fishless and fish-bearing lakes, as shown in the table “Occurrences and Abundances of Invertebrates in Fishless and Fish-Hosting Lakes in the Sierra Nevada”, below. The table does not include fairy shrimp. Bradford and others (1998) didn’t mention them. Knapp and others (2001) explicitly ignored rare species. The table below does not include Bradford and others’ (1998) results for 8 lakes with pH less than 6.0. None of those acidic lakes had fish. Thus, “fishless” for Bradford and others’ (1998) results in the table means non-acidic lakes without fish. Of the non-acidic lakes, 7 had fish and 16, 17, or 18 did not (according to the caption of Figure 3). Including the acidic lakes, the 33 surveyed lakes of Bradford and others (1998) had areas of 0.12-30.5 hectares (0.3-75 acres) (median=1.4 hectares, 3.5 acres), maximum depths of 0.3-10.0 m (1-33′) (median=2.6 m, 8.5′), and elevations of 3,130-3,672 m (10,270-12,050′) (median=3,470 m, 11,385′). Bradford and others (1998) also published means and standard deviations of pH and major ion concentrations.

*Previously stocked lakes without fish at time of survey not included; “fishless lakes” were never stocked.

^Only lakes with pH > 6.0.

n.s. – not significant (p > 0.05 for Knapp and others (2001) and p > 0.10 for Bradford and others (1998))

same – bars for fishless and fish-hosting lakes in the graphs have about the same height.

Bradford, D. F., Cooper, S.D., Jenkins, T.M., Kratz, K., Sarnelle, O., and Brown, A.D., 1998, Influences of natural acidity and introduced fish on faunal assemblages in California alpine lakes: Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, v. 55, p. 2478-2491.

Knapp, R.A., Matthews, K.R., and Sarnelle, O., 2001, Resistance and resilience of alpine lake fauna to fish introductions: Ecological Monographs, v. 71, no. 3, p. 401-421.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Knapp and others (2001) distinguished between “never-stocked”, “stocked-fish-present”, and “stocked-now-fishless” lakes. The “stocked-now-fishless” results are not included in the table as the presence of species in such cases is controlled by recolonization as much as by original presence. Thus, “fishless” for Knapp and others’ (2001) results in the table means “never-stocked”. Their benthic macroinvertebrate samples were from 67 “never-stocked” lakes and 100 “stocked-fish-present” lakes. Benthic macroinvertebrates are large enough to be seen and spend at least part of their time on the bottom of the pond. Their zooplankton samples (animals that mostly swim or float) were from 62 “never-stocked” lakes and 89 “stocked-fish-present” lakes. The surveyed lakes of Knapp and others (2001) had areas of at least 0.5 hectare (1.2 acres), depths of at least 3 m (10′), and elevations of 2,870-3,600 m (9,420-11,810′).

Potentially confounding variables were considered. Knapp and others (2001) looked at elevation, area, depth, solar input (important for estimating damage by ultraviolet light), sampling day, and percent silt and, because of their interest in amphibians, the numbers of other lakes within 1 km (0.6 mile) and of other ponds within 250 m (820′). Bradford and others (1998) considered elevation, area, and depth along with pH, conductivity, and the concentrations of major ions. Although there were some significant differences in these variables between fishless and fish-hosting lakes, “the strong effects of lake category [e.g., never-stocked] on faunal assemblage structure were independent of the confounding influences of habitat variables” (Knapp and others, 2001). Bradford and others (1998) found that fishless lakes had smaller areas and shallower depths, on average, than lakes with fish but that is because smaller lakes are less likely to be stocked. An inverse correlation of lake size with presence of an invertebrate species has no biological significance.

Neither Bradford and others (1998) nor Knapp and others (2001) published their data but they did show bar graphs of the percentages of lakes with various taxa (species groups) and of the average abundances (individuals of a taxon per the number of net sweeps for the samples) in the lakes along with levels of statistical significance, or p values. The negative correlations between fish and large zooplankton species found by Stoddard (1987) were confirmed. Both Hesperodiaptomus shoshone and Daphnia middendorffiana were much more commonly found in fishless lakes than in lakes with fish. Those collected in samples were commonly longer than 2 mm (Bradford and others, 1998). D. middendorffiana wasn’t found by Bradford and others (1998) in any lakes with fish. Daphnia rosea and Chydorus sphaericus were shorter than 1 mm (Knapp and others, 2001) and weren’t significantly affected by fish predation. Rotifers were even smaller and the genera Keratella and Polyarthra were significantly more abundant in fish-hosting lakes. Because fish eat most of the large copepod predators, rotifers can proliferate.

Both Bradford and others (1998) and Knapp and others (2001) demonstrated that greater percentages of fishless lakes have mayfly larvae, dytiscids, water boatmen, and backswimmers than fish-hosting lakes do. Although quite low, the p values don’t do justice to the visual impact of the bar graphs. On the graphs of Bradford and others (1998), the percentages of fishless lakes that have mayfly larvae and water boatmen is about 50% and 85%, respectively, while the percentages of fish-hosting lakes that do looks close to 0%. The contrast isn’t quite as dramatic for dytiscids. Bradford and others (1998) also reported that they found backswimmers only in fishless lakes.

The abundance data of Knapp and others (2001) complements the percentage of lakes data and indicates that some invertebrate populations that are free from fish predation are much, much larger than those in lakes with fish.

Knapp and others (2001) were surprised to find that the great preponderance of caddisfly larvae were found in fishless lakes. Caddisfly larvae are protected by cases they construct of local materials like sand or small bits of vegetation. Some such cases are good camouflage. Caddisfly larvae can also crawl between pebbles and rocks to hide from fish. Nonetheless, they generally weren’t present in fish-hosting lakes. For the species found by Knapp and others (2001), neither cases nor camouflage were adequate protection from fish.

Smaller size can’t explain the different results for the Limnephilus, Hesperophylax, and Polycentropus genera of caddisflies (Knapp and others, 2001). Caddisflies of the genus Limnephilus are about 10 mm long, the same as Polycentropus (Knapp and others, 2001). They may have some behavioral advantage that makes them less visible or less appealing to fish and allows them to survive in lakes with fish. Or there may have been some idiosyncrasy of the fish-hosting lakes where Knapp and others (2001) found the genus, such as bottom type. An unspecified species of the same family was rarely found in fish-hosting lakes by Bradford and others (1998).

Mosquito larvae, genus Culex, are not relatively small but Knapp and others (2001) offered an explanation for their common presence in fish-hosting lakes. They suggested that Culex could better hide from fish than the other large invertebrates because they prefer to hang out in aquatic vegetation. Moreover, they could benefit from the near disappearance of large insect predators such as dytiscids. A similar explanation might apply to chironomids.

The more common presence of Acari in fish-hosting lakes was expected by Knapp and others (2001). They taste bad. Water mites can also be smaller than 1 mm. A tiny graph in Knapp and others (2001) suggests that those collected were less than 2 mm and possibly less than 1 mm long, on average.

It is not that there is some physical or chemical characteristic in the fish-hosting lakes that is inimical to aquatic invertebrates. Some caddisfly species and small-bodied cladocerans and rotifers do have similar distributions in fishless and fish-hosting lakes. Either fish predation is the cause of the different distributions or it is a coincidence. The statistics prove it is not a coincidence at the 99.9% confidence level (for the larger data set of Knapp and others, 2001). Strong correlations between the large-bodied invertebrates also rule out a coincidence. The coincidence would have to affect mayflies, water boatmen, and dytiscids similarly. These species have similar correlations of 0.44, 0.48, and 0.63 with the principal component axis 1 for macroinvertebrates derived by Bradford and others (1998). It would also have to affect Hesperodiaptomus shoshone and Daphnia middendorffiana similarly. They have correlations of 0.78 and 0.80 with the principal component axis 2 for zooplankton.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

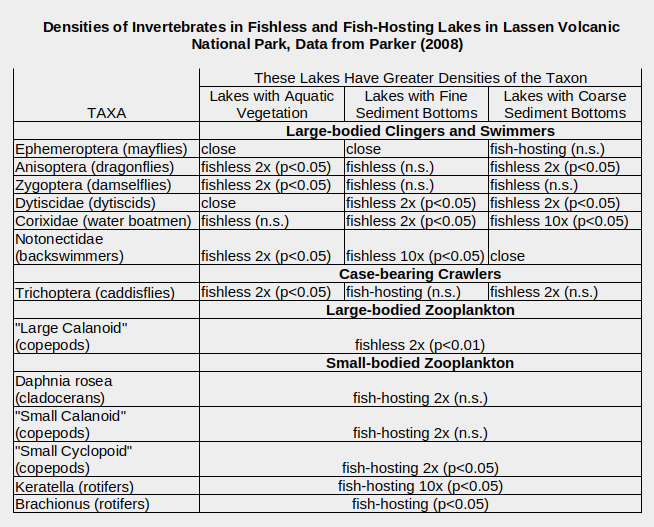

Zooplankton and Benthic Invertebrates in Lassen Volcanic National Park

Like Bradford and others (1998) and Knapp and others (2001), Parker (2008) sampled a large variety of aquatic animals to determine fish impacts. He surveyed 32 fishless lakes and 10 lakes with fish in Lassen Volcanic National Park in the northern Sierra Nevada. Lake areas ranged from less than 1 to 256 hectares (less than 2.5 to 632 acres), depths from 2 m to greater than 64 m (6.5′ to greater than 210′), and elevations of 1,700-2,700 m (5,580′-8,860′). Fishless lakes were no deeper than 32 m (105′) or larger than 32 hectare (79 acres). Fish-bearing lakes did not occur above 2,500 m (8,200′). As for the data of Knapp and others (2001), these confounding habitat variables are unlikely to control the distribution of invertebrate species. Data by lake were not published but the dragonfly Sympetrum, giant water bugs of the family Belostomidae, the water scorpion Ranatra brevicola, 5 species of dytiscid, a Gyrinux whirligig beetle, a Tropisternus water scavenger beetle, the cladoceran Holopedium gibberum, mosquitoes, the copepod Hesperodiaptomus kenai, the chironomid Chaoborus americanus, and the fairy shrimp Streptocephalus seali were absent from lakes with fish but present in fishless lakes. With the possible exception of H. gibberum, these are all large-bodied species. H. kenai is typically 2 mm (0.08″) long (Wilson, 1953).

Parker (2008) presented bar graphs of macroinvertebrate densities (individuals per net sweep) by lake type – either vegetated, with fine sediment bottom, or with coarse sediment bottom. The table “Densities of Invertebrates in Fishless and Fish-Hosting Lakes in Lassen Volcanic National Park”, below, shows results similar to those for Knapp and others (2001) except for mayflies. Some species of mayfly can maintain stable populations in the presence of fish even if the populations would be larger without fish (e.g., Caudill, 2005).

“fishless” lakes include an unknown number of lakes that were stocked but don’t currently have fish.

For other taxa that were completely absent from fish-hosting lakes, see text.

2x, 10x – heights of bars for fishless and fish-hosting lakes look at least 2 or 10 times different.

n.s. – not significant (p > 0.05).

close – bars for fishless and fish-hosting lakes have somewhat different heights in the graph.

Parker, M. S., 2008, Comparison of limnological characteristics and distribution and abundance of littoral macroinvertebrates and zooplankton in fish-bearing and fishless lakes of Lassen Volcanic National Park: National Park Service, Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/KLMN/NRTR—2008/116, 26 p.

Dragonflies, damselflies, dytiscids (except those in vegetated lakes), water boatmen, and backswimmers (except those in coarse-sediment lakes) were more abundant in fishless lakes, although not always significantly so. Caddisflies were more abundant in fishless lakes that were vegetated or had coarse sediment but not in those with fine sediment. The pattern for zooplankton also fits the expected consequences of fish predation with large-bodied species more abundant in fishless lakes and small-bodied species more abundant in lakes with fish.

Parker’s (2008) data could have underestimated the negative effects of fish on large-bodied invertebrates. Fish-stocking in the park was stopped in the 1970s. Records of previous fish-stocking are incomplete but Parker (2008) inferred that all the lakes surveyed had been stocked. Because of that, some now fishless lakes may not have been recolonized by some invertebrate species or may have been recolonized only recently. If that is the case, they would look more like fish-hosting lakes where such species have been eliminated or reduced by predation.

Confirmation that Fish Diets Include Benthic Invertebrates

Finlay and Vredenburg (2007) used a different approach but their results also support the conclusion that fish predation reduces or eliminates populations of large invertebrates. They surveyed 20 fishless lakes and 21 lakes stocked with fish in Kings Canyon National Park at elevations of 3,000-3,500 m (9,840-11,480′). They stated “invertebrate predators, common only in fishless lakes”. The predators were “primarily” dytiscids (order Coleoptera, family Dytiscidae) and corixids (sub-order Heteroptera, family Corixidae – water boatmen). As Finlay and Vredenburg (2007) were interested in the food competition between fish and frogs for Ephemeroptera, they didn’t provide details on the distribution of invertebrate predators. Instead, they used carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios to demonstrate that the prey of introduced fish consisted entirely of “benthic grazers”, “primarily” Ephemeroptera (mayflies) and Trichoptera (caddisflies). Small-bodied cladocerans and copepods were eaten very sparingly or not at all.

Wrap-Up Sierra Nevada

Knapp and Matthews (2000) summarized the effects of fish on benthic invertebrates by stating “large conspicuous species are eliminated, while burrowing or otherwise inconspicuous species are relatively unaffected”. As a result, “several conspicuous taxa of mayfly larvae (Ephemeroptera), caddisfly larvae (Trichoptera), aquatic beetles (Coleoptera) and true bugs (Corixidae)” dominate fishless lakes but “are rare or absent in lakes with introduced trout”. Similarly, for water-column invertebrates, fish-stocking “shifts the zooplankton community from one dominated by large-bodied species to one dominated by smaller-bodied species”. If fish predation has had such large impacts on so many invertebrate species in the Sierra Nevada, it must also have impacted fairy shrimp populations for the worse. How many populations were eliminated will never be known.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been Beyond the Sierra Nevada?

Negative correlations between fish and various invertebrate taxa would be more convincing if they were seen in other areas and in other ecosystems.

in Utah

Stocked trout in the mountains of Utah severely reduced populations of large-bodied invertebrates there. “Densities of large benthic (e.g., caddis larvae, Hemiptera, and amphipods) and planktonic (Chaoborus and some Diaptomidae) taxa were 3- to 7-times less abundant in lakes with trout than without” (Carlisle and Hawkins, 1998, abstract only). There was nothing wrong with the water. The small cladoceran Daphnia rosea and cyclopoid copepods did fine in the trout lakes. The differences in invertebrate densities could not be explained by different sand, cobble, or vegetation bottom types. Trout ate them: “differences in habitat did not appear to mediate effects of trout predation on benthic invertebrate assemblages”.

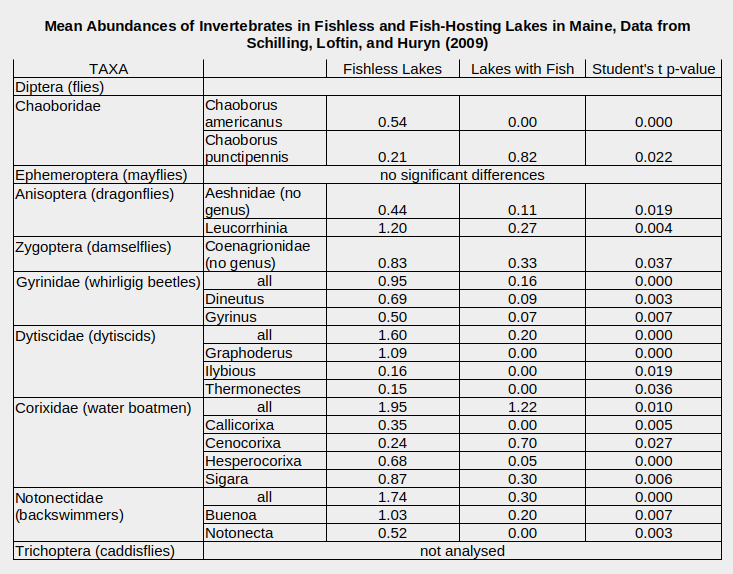

in Maine

A comprehensive study of 16 fishless and 18 fish-hosting lakes in the Eastern Lowlands and Foothills and in the Central and Western Mountains in Maine documented major differences in the aquatic communities with or without fish (Schilling and others, 2009). Fishless and fish-hosting lakes had mean areas of 2.8 and 3.8 hectares (6.9 and 9.4 acres) and depths of 6.3 and 6.7 m (20.7′ and 22.0′), respectively. As shown in the table “Mean Abundances of Invertebrates in Fishless and Fish-Hosting Lakes in Maine”, below, the fishless lakes had significantly greater abundances of some dragonflies, some damselflies, some whirligig beetles, some water boatmen (Cenocorixa was more abundant in fish-hosting lakes), and some backswimmers, which all have relatively large bodies. Tellingly, the water boatman genus Callicorixa, the backswimmer Notonecta insulata, the dytiscid Graphoderus liberus, and Chaoborus americanus were widespread in fishless lakes but absent from lakes with fish. An additional 7 species were absent from fish-hosting lakes and present in only a few fishless lakes. There wasn’t much difference in the distribution of mayflies. Water striders of the family Gerridae were only found on lakes with fish. Overall, Schilling and others (2009) found that “Fish presence or absence was a stronger determinant of community structure in our study lakes than differences in lake origin and physiography”. Schilling and others (2009) did not identify any of the fish-hosting lakes as stocked. Whether the fish were native or not, the results indicate that the long-term presence of fish drives the composition of compatible aquatic communities far from those found in fishless lakes and completely excludes some species, which would likely include fairy shrimp.

Only the taxa with significant differences between fishless and fish-hosting lakes are listed.

p values of 0.05 or less indicate 95% or better confidence that the abundance difference between lake types is not due to chance.

Schilling, E.G., Loftin, C.S., and Huryn, A.D., 2009, Macroinvertebrates as indicators of fish absence in naturally fishless lakes: Freshwater Biology, v. 54, p. 181-202.

in the Tatra Mountains, Poland

Cladocerans and most copepod species have been extirpated from stocked lakes in the Tatra Mountains of Poland while smaller rotifers have increased in abundance over several decades (Gliwicz and Rowan, 1984). The cladocerans Daphnia pulicaria and Holopedium gibberum are abundant in a fishless lake in the same region. These cladocerans are certainly larger than rotifers but their sizes were not given. They are likely larger than the copepod Cyclops abyssorum tatricus, which continues to survive in lakes with fish. The mean body length of that cyclopoid is 0.77 mm (0.03″). Samples of fish stomachs indicated Cyclops abyssorum tatricus accounted for less than 1% of food over most of the year. However, copepods bearing more visible dark eggs became a major food item when they appeared in April. As a result, fish diets changed to about 40% copepods (but with a huge standard deviation). This is the same story of fish predation severely reducing populations of more visible zooplankton.

in the Alps, Slovenia

In the Alps of Slovenia, the relatively large copepod Arctodiaptomus alpinus was eliminated within 7 years of the introduction of alpine charr into a previously fishless lake (Brancelj, 1999).

In a study of copepods in a wide variety of 160 lakes and ponds of the Alps of Italy, Slovenia, and Austria, Jersabek and others (2001) stated that stocked fish “normally excluded the occurrence of calanoid copepods”. Specifically for Arctodiaptomus alpinus, the “different intensity of fish-stocking” “reflected” its distribution. Calanoids are commonly larger than cyclopoids but sizes weren’t given. Moreover, “the distribution pattern of all planktonic species, including C. abyssorum tatricus, was negatively associated with that of fish.”

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

in the Alps, Italy

The zooplankton in 12 alpine lakes of a national park in the western Alps of Italy have low species diversity and most species are little affected by the presence of fish (Magnea and others, 2013). The exception is Daphnia gr. pulicaria. It was the only species with an average body length greater than 2 mm (0.08″). It was present in 4 of 6 fishless lakes and in none of the 6 lakes with fish. Smaller species were widespread. The calanoid copepod Arctodiaptomus alpinus (average body length 1.25 mm, 0.05″), the cyclopoid copepod Cyclops abyssorum (1.26 mm, 0.05″), and the cladoceran Daphnia gr. longispina (1.15 mm, 0.045″) occurred in 5 or all of the fishless lakes and in 5 or all of the lakes with fish. Very small rotifers (0.12 mm, 0.005″) inhabited all of the fishless and fish-hosting lakes. The small cladoceran Chydorus sphaericus (0.34 mm, 0.013″) was more common in lakes with fish (5 of 6) than in fishless lakes (2 of 6) (Magnea and others, 2013).

Fish predation on zooplankton by species was elucidated by a different sampling of trout stomachs from 7 lakes (Tiberti and others, 2014). Rotifers were not found in the stomachs. Smaller fish ate all the copepod and cladoceran species but fish longer than 20 cm (7.9″) ate only the largest, i.e., Daphnia gr. longispina and Cyclops gr. abyssorum. Although only about 6% of the stomachs of large trout had zooplankton, that was nevertheless sufficient to reduce the densities of the largest species. 3,100 Daphnia gr. longispina individuals were found in the stomach of a single trout (Tiberti and others, 2014).

An analysis of the ecological impact of fish in the same area of Italy found the “local extinction in stocked lakes of both more vulnerable taxa (in particular Ditiscidae, Corixidae, Tricoptera, and Acari), as well as, entire groups of organisms sharing the same modes of existence, such as clinger and swimmer macroinvertebrates” (Tiberti and others, 2013). In contrast, burrowing species such as chironomids and oligochaetes were more abundant in lakes with fish.

in the Pyrenees, Spain

Both size and behavior affect the ability of dytiscid species to survive in lakes with fish in the Pyrenees. The 4 most common dytiscid species found in 45 lakes (17 fishless) in the Pyrenees were Agabus bipustulatus, Platambus maculatus, Hydroporus foveolatus, and Boreonectes ibericus (De Mendoza and others, 2012). Percentages of host lakes that were fishless were 86% (12 of 14 lakes) for Agabus, 0% for Platambus (0 of 7), 43% for Boreonectes (3 of 7), and 47% (9 of 13) for Hydroporus. Due to strong correlations of temperature, fish, and vegetation with altitude and, hence with each other, the data were analyzed using canonical correspondence analysis, which generated some nice splatter diagrams. Further, generalized additive models demonstrated that fish presence explained more of the variance than temperature for Agabus. Vegetation and, by implication, hiding in vegetation was most important for Boreonectes and somewhat important for the other species. “[W]hen partialling out the effects of temperature, it was found that salmonids and macrophytes indicated that predation may explain the current overall distribution of dytiscids better than temperature” (Mendoza and others, 2012).

Mean body lengths can explain most of the differences in dytiscid distributions but were not tested statistically. Mean lengths were 9.6 mm for Agabus, 7.6 mm for Platambus, 4.0 mm for Boreonectes, and 3.4 mm for Hydroporus (not measured by Mendoza and others, 2012, but taken from Ribera and Nilsson, 1995). The lesser impact of fish on Boreonectes and Hydroporus and strong effect on Agabus could be attributed to the fish dietary preference for larger prey.

The occurrence of Platambus only in lakes with fish cannot be a result of size-selective predation because it is almost as big as Agabus (assuming sizes were the same as those in the cited work). Platambus occurs in streams as well as lakes and is a poor swimmer whereas Agabus is a good swimmer (De Mendoza and others, 2012). A tendency to cling to the bottom and swim less may reduce its chances of being eaten by fish. It may also benefit if fish eliminate competition or predation by Agabus (my suggestion). Platambus does not occur in any lakes that have Agabus.

in Patagonia, Argentina

For lakes of the Patagonian steppe, 1 figure says it all. For the 6 lakes with fish (5 stocked, 1 natural), the medians and 10th and 90th percentiles of body lengths of the dominant cladoceran species are all less than 1.0 mm (0.04″) (Reissig and others, 2006, Figure 5). For 12 fishless lakes, they are all greater than 1.7 mm (0.07″) except for 2 lakes which lacked any large cladoceran. The gap between sizes in fishless and fish-hosting lakes was not as clear for copepods because the fishless lakes had 2-4 species ranging from the smallest to the largest and 1 lake with fish had the 2 largest species as well as 2 smaller ones (Reissig and others, 2006, Figures 3 and 4). Even so, the difference of the maximum sizes of copepods between lakes with and without fish was significant (p = 0.005). Rotifers, which are smaller than copepods, were considerably more abundant in lakes with fish than those without. Reissig and others (2006) also noted that the largest copepod had been extirpated from 1 lake.

Fish have also affected the phytoplankton in Patagonian lakes. Stocked lakes have much higher concentrations of phytoplankton than fishless lakes: 102,642-5,493,620 cells per milliliter compared to 226-7,603 cells per milliliter (Reissig and others, 2006). The ratio of phytoplankton less than 0.02 mm to that greater than 0.02 mm is far lower in stocked lakes: 0.0003-0.0338 compared to 0.6964-2.3037. The types of phytoplankton also differ dramatically. By volume, stocked lakes have mostly Cyanophyceae and “others” whereas fish-free lakes are dominated by Chlorococcales and Zygnematales with smaller amounts of Cryptophyceae + flagellated Chrysophyceae less than 0.02 mm. The 1 lake with native fish is in a phytoplankton class by itself. The predominance of cyanobacteria in stocked lakes may be a result of fish feces recycling phosphorus or to the elimination of the cladoceran genus Daphnia, which has high phosphorus requirements, or both (Reissig and others, 2006). The preponderance of phytoplankton less than 0.02 mm in fishless lakes could be due to preferences of large omnivorous or herbivorous copepods for larger plankton. With fewer large copepods, fish-hosting lakes would allow large phytoplankton species to flourish.

Data summarized above indicate that the effects of fish-stocking observed in the Sierra Nevada are not the result of unique local conditions.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

What Have the Effects of Fish-stocking Been on Vertebrates?

Amphibians in the Sierra Nevada

Except for Stoddard (1987), the Sierra Nevada studies summarized above were not supported by a specific interest in entomology or a general interest in aquatic biology. They were supported by alarm over decreasing numbers of mountain yellow-legged frogs. A 1994 resurvey of the Sierra Nevada lakes surveyed in 1915 found that only 15% of the lakes previously reported to have the frogs still had the frogs (Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2003). During the Sierra Lakes Inventory Project’s 1995-2002 survey, mountain yellow-legged frogs were found in 566 lakes and fish in 662 lakes. Of the lakes with mountain yellow-legged frogs, 86% lacked fish and 14% had fish. It is thanks to the frogs we now also know that many invertebrate populations have disappeared.

A “dramatic decline and possible extinction” in populations of Cascades frog in Lassen Volcanic National Park “and the surrounding region” was reported by Parker (2008), citing previous studies. Parker (2008) observed that his study “clearly showed a negative association between fish and certain amphibian species within all lentic [lake] habitats”.

Amphibians in the Cascade Mountains, Oregon and Washington

Concern about amphibians has been global. Negative effects of fish-stocking have been documented for the Cascade frog in Washington; the Pacific tree frog in California and Oregon; the long-toed salamander in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington; the northwestern salamander in Washington; and the tiger salamander in Colorado (Dunham and others, 2004, Table 2). In the North Cascade National Park Service Complex, larvae of long-toed salamander were significantly less abundant in lakes with fish than in lakes without fish on the east slope of the Cascade Mountains (Liss and others, 1995). On the west slope, tiger salamander is more common and survives in some lakes with fish but larvae are less abundant than in lakes without fish.

Amphibians in the Cantabrian Mountains, Spain

Stocked fish affect the distributions of several amphibian species in the Cantabrian mountains of northern Spain. Of 8 “large and permanent pools and lakes” with fish, 3 lakes had no amphibian species, 3 had 1 species, and 2 had 2 species (excluding Ercina, which was reportedly stocked but lacked fish) (Braña and others, 1996). 7 fishless lakes each have 3-5 species of amphibians. Rana temporaria was the only amphibian which occurred in more than 1 stocked lake (excluding lake Ercina). 6 species were found only in fishless lakes. Another study found that the toads Bufo bufo and Alytes obstetricans were widespread regardless of fish but the newts Triturus helveticus, Triturus alpestris, and Triturus marmoratus were negatively affected by introduced fish (Orizaola and Braña, 2006, abstract only). Bufo bufo and Alytes obstetricans had been found only in fishless lakes by Braña and others (1996).

Amphibians in the Neila Mountains, Spain

In the Neila Mountains of central Spain, reproducing populations of the 4 species Bufo calamita, Triturus helveticus, Triturus marmoratus, and Hyla arborea were found in all 3 sample years in 3 fishless ponds (Martínez-Solano and others, 2003). The latter 3 were also found in 2001 in the one pond with cyprinid but not salmonid fish. None of the 4 species were found in 3 ponds with salmonid fish. The exclusion of these species from ponds with fish is at least partly due to amphibian preferences for shallow ponds with submerged vegetation and muddy bottoms. Lakes and ponds favored by trout tend to be deep and rocky. Bufo bufo, Alytes obstetricans, and the frog Rana perezi inhabited both fishless and fish-hosting ponds. 3 fishless ponds had all 7 species of amphibians for all 3 sample years but for 2 different years in 2 different ponds. Salamandra salamandra was found in 5 fishless ponds (2 of these ponds had only S. salamandra) and 1 pond with fish in 1981, in 2 fishless ponds (both the S. salamandra only ponds) in 1991, and in no ponds in 2001 (Martínez-Solano and others, 2003). Populations of S. salamandra in other areas of Spain have also disappeared. Stocked fish are likely partly responsible for the disappearances (Martínez-Solano and others, 2003).

Amphibians in the Alps, Switzerland

The newt Ichthyosaura alpestris (previously Triturus alpestris) in the Alps of southern Switzerland is strongly affected by fish predation but has the resilience to bounce back (Denoël and others, 2016). Fish were present in “Pianca Lake” in 1972 and newts were absent. In 1989, newts were present but fish were absent. The lake was again stocked with fish in 2009, 2011, and 2012. Newts were not found in the lake in 2014. However, at that time they were found in small pools without fish nearby. They were also present in another lake and adjacent pools that had a low density of minnows but not in a lake with abundant brook trout (Denoël and others, 2016). The key to newt persistence in the presence of fish was pools acting as refuges while the lake had fish. However, persistence is not guaranteed. Pool populations are much smaller than those of lakes and are more sensitive to drought. Of course, if the fish don’t die out again, the newts will never return to the lake.

Reptiles in the Sierra Nevada

The effects of fish-stocking extend from the aquatic realm to the terrestrial and avian realms. This is important for fairy shrimp because such effects can bounce back to impair the ability of fairy shrimp to colonize new ponds. Terrestrial animals and birds serve as dispersal agents for fairy shrimp eggs.

Mountain garter snakes feed on mountain yellow-legged frogs, among other species. Of about 1,000 lakes in Kings Canyon National Park, where there has been no fish-stocking since 1970, garter snakes were found in 62. Among a similar number of lakes in the John Muir Wilderness, where fish-stocking continues, no mountain garter snakes were found (Pacific Southwest Research Station, 2003).

Finches in the Sierra Nevada

Fish-stocking has negative effects on some bird populations. The food gray-crowned rosy finches use to feed their young in the Sierra Nevada is “primarily” insects (Epanchin and others, 2010) and much of that is mayflies. Fish eat mayfly larvae. In the study area, all 12 fishless lakes had mayfly larvae but only 2 of 12 lakes with fish did. Moreover, the densities of larvae were about a factor of 10 less in the 2 lakes with fish than in the lakes without fish. Rosy finches were 4 to 10 times more abundant at fishless lakes than at lakes with fish during mayfly hatches (for the lakes with fish and no mayflies, timing of hatching was determined by a nearby fishless lake). Whether fish-stocking reduced populations of rosy finches or not was beyond the scope of Epanchin and others’ (2010) study.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Lesser Scaup in southern Saskatchewan, Canada, and the upper Midwest, U.S.A.

2 studies have identified strong links between the numbers of migrating lesser scaup and the densities of amphipods, a dominant food, at wetlands on the prairies north and south of the Canada – United States border (Lindeman and Clark, 1999; Anteau and Afton, 2009). Fish eat amphipods. A 3rd study in the region found strong negative correlations between amphipod densities and fish densities and referred to a decades long decline in lesser scaup numbers (Carleen and others, 2024). Due to climatic and human factors, fish have become much more common over the same time frame and threaten to turn North America’s “duck factory” into a “fish factory” (McLean and others, 2016).

Ducks in Norway

In Norway, goldeneyes were found more often at lakes without fish than at lakes with fish (Eriksson, 1979, abstract only). Experimental removal of fish from 1 lake increased numbers of mayfly larvae, Odonata larvae (e.g., damselflies, dragonflies), water bugs (e.g., water boatmen, backswimmers), dytiscids and Chaoborus larvae. Ducks subsequently increased their use of the experimental lake.

Ducks in Finland

A survey of 38 lakes in Finland found a negative correlation between the numbers of common goldeneyes and green-winged teals at a lake and the abundance of yellow perch in the lake (McParland, 2005). The same did not hold true for mallards.

Ducks in Sweden

Mallards were most common at Swedish lakes with low fish densities and mallard ducklings were able to eat the most invertebrates at lakes with the fewest fish (McParland, 2005).

Flamingos in the Andes, Peru

Surveys of the flamingo, fish, and zooplankton populations in 20 high-elevation lakes of southern Peru found a negative relation between flamingos and fish (Hurlbert and others, 1986). At the 8 lakes without fish, the numbers of flamingos (total visual counts) ranged from 0 (4 of 14 surveys) to 4,457 with an average (average of mean and median) of 245 per survey. At the 12 lakes with fish (either native or exotic), the range was 0 (10 of 24 surveys) to 205 birds with an average of 25 per survey. The reason flamingos prefer lakes without fish is that these lakes have much greater abundances of the large zooplankton that they eat, specifically calanoid copepods and cladocerans (commonly Daphnia in fishless lakes). The average (average of mean and median) biomass of calanoids in fishless lakes was 1,292 micrograms per liter and in lakes with fish it was 54 micrograms per liter. In all surveys of fishless lakes (other than 2 saline lakes inhabited by fairy shrimp of the genus Artemia), close to 100% of the copepods were calanoids. In most surveys that found fish, close to 0% of copepods were calanoids but a minority of surveys had 50-100% calanoids. Conversely, the small species of cyclopoid copepods and rotifers were more abundant in lakes with fish by factors of 17 and 6, respectively.

Fish diets overlap with those of flamingos. Native fish of the genus Orestias “feed primarily on cladocerans, copepods, amphipods, and insect larvae, but also on fish eggs, filamentous algae, and phytoplankton” (Hurlbert and others, 1986). Introduced Basilichthys bonariensis have a similar diet but larger individuals also eat other fish. Introduced rainbow trout mostly eat other fish but they also eat amphipods, insects, snails, tadpoles, copepods, and cladocerans (Hurlbert and others, 1986).

Coots and Swans in Patagonia, Argentina

In “Laguna Blanca” National Park in northern Argentina, there is a negative relation between the presence of fish and the abundance of black-necked swans and coots (Ortubay and others, 2006). Fish were introduced in 1965 to “Laguna Blanca”. Bird densities were not quantified but the effects of fish on aquatic communities were determined by comparing benthic macroinvertebrate populations in the large, eutrophic, fish-hosting “Laguna Blanca” with those in 3 much smaller, shallower, fishless ponds nearby. Graphically (Ortubay and others, 2006, Figure 2), amphipods (genus Hyalella) and copepods were much more abundant in the fishless ponds than in “Laguna Blanca”. Ostracods were more abundant in “Laguna Blanca” and the smallest, most saline fishless pond than in the other 2 fishless ponds. Acari (mites) were present only in “Laguna Blanca”. “Laguna Blanca” had the least benthic biomass. Percichthys colhuapiensis fish collected from “Laguna Blanca” ate abundant snails (Planorbidae), copepods, chironomid larvae, amphipods (May only), cladocerans (March only), and ostracods (January only) in addition to terrestrial insects (March only) (Ortubay and others, 2006, Figure 4). The size of the ostracods was not given but the other prey species were probably large. Other possibly fish-related impacts include the disappearance of the amphibian Atelognathus patagonicus between 1984 and 1986 and of tadpole shrimp (Notostraca) more recently than 1991. Negative effects across populations of birds, amphibians, amphipods, copepods, and notostracans are most easily explained by fish predation.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

Most alpine fairy shrimp are as large as, or larger than, the amphipods, water boatmen, dytiscids, backswimmers, and caddisfly larvae and much larger than the cladocerans and copepods that suffered from fish predation in the studies summarized above. Making matters worse, fairy shrimp don’t hide in vegetation, don’t cling to the pond bottom (except for brief feeding), swim slowly, and are always available to be eaten by visual predators because they swim throughout the daylight hours. Consequently, the effects of fish on pre-stocking fairy shrimp populations would be at least as bad as those on the benthic macroinvertebrates and zooplankton considered above. The absence of long-lived, co-existing populations of fish and fairy shrimp anywhere in the world further suggests that fish introduced into Sierra Nevada lakes extirpated every population of fairy shrimp that they encountered.

Summing up, the stocking of fish in the Sierra Nevada has exterminated or drastically reduced some unknown number of populations of amphibians, large-bodied insects, amphipods, cladocerans, and copepods. The examples above demonstrate that these effects are not unique to the Sierra Nevada or to alpine lakes in the western United States. Even ignoring fairy shrimp, the effects have been geographically and biologically far-reaching. Fish-stocking is a human choice. The intentional, extensive elimination of a species (analogous with human ethnic group) from lakes (analogous with country) or the reduction of populations to less than half of what they were before is what I call “zooicide”. Exterminating numerous populations of several species at the same time is more zooicide. Continuing to stock lakes with fish and thereby preventing previously eliminated species from recolonizing their home waters is long-term zooicide.

Back to Fish-stocking Zooicide in the Sierra Nevada

East-Central Sierra Nevada – top

Virginia Divide Double Ponds (Bridgeport Ranger District, Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest; Hoover Wilderness)

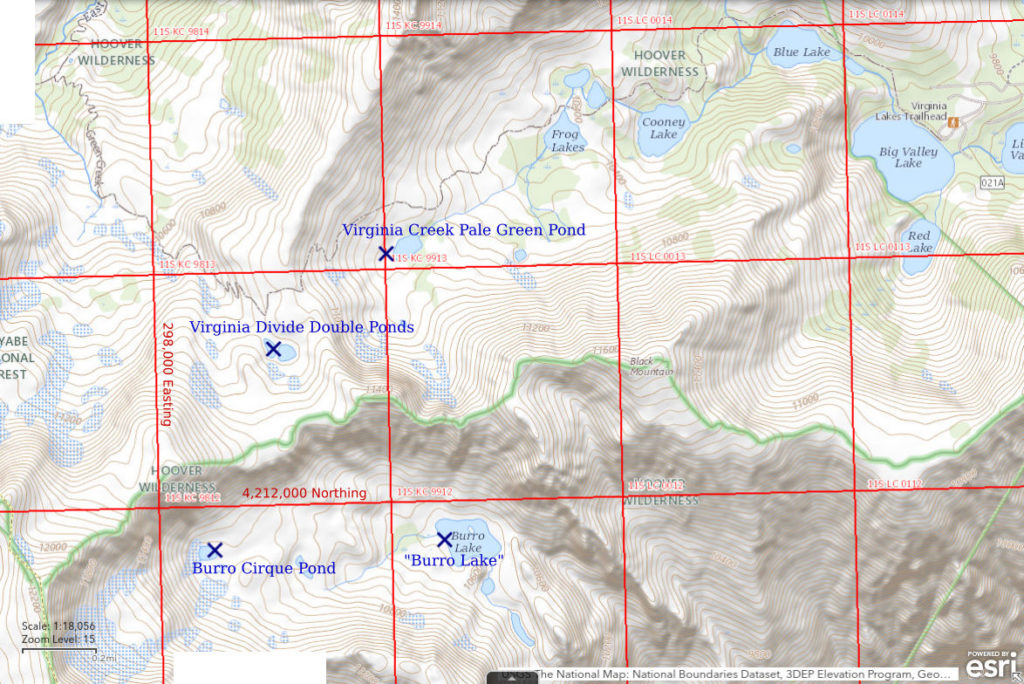

___This map is a screenshot of The National Map (Go to The National Map). The U.S. Geological Survey generally does not copyright or charge for its data or reports (unless printed). A pond location is indicated by an “X”, which corresponds to the coordinates given in the data spreadsheet. Labels in quotations are from 7.5-minute topographic quadrangles.

___Red lines are the U. S. National Grid with a spacing of 1,000 m and intersection labels consisting of the UTM zone (e.g., 11S, 12T), a 2-letter 100-km square designation (e.g., LC, XN), and a 4-digit number. The first 2 digits of the number represent the 1,000-meter Easting and the second 2 digits the 1,000-meter Northing, as seen in the example Easting and Northing. Unlike latitude and longitude, the National Grid is rectilinear on a flat map, the units of abscissa and ordinate have equal lengths, and the units (meters) are measurable on the ground with a tape or by pacing.

___There is no private or state land on this map. All the lands are public.

Virginia Divide Double Ponds are a little more than 24 km (15 miles) southwest of Bridgeport. They are in a low spot on the broad ridge that forms the drainage divide between Virginia Creek and East Fork Green Creek. There are 2 ponds which are close together and a couple hundred meters south of the hiking trail. They are not on the Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest’s recreation map for the Bridgeport Ranger District but are on the 7.5-minute topographic quadrangle. The slope to the west of the ponds probably collects a lot of snow.

Access is the hiking trail from the “Virginia Lakes” trailhead. There is an elevation gain of about 450 m (1,480′) but the distance is less than 5 km (3 miles).

Elevation: 3,376 m (11,075′)

September 8, 2016

Water levels are well below the high-water mark but it may not be too late for fairy shrimp.

- Bigger pond is 20 m x 40 m, smaller one is less than 20 m both ways; depths not estimated.

- Water clear.

- No fairy shrimp.

- Caddisfly larvae (Trichoptera).

Virginia Divide Double Ponds, looking north along the ridge between East Fork Green Creek Canyon (left) and Virginia Creek Canyon (right). The hiking trail can be seen faintly to the left of the rocky knoll at center.

August 26, 2021

Stopped by on the way to “Burro Lake”. It’s been another dry year but there is some water.

- Bigger pond is 15 m x 40 m and up to 50 cm deep; smaller pond less than 15 m across and less than 15 cm deep.

- Clear water.

- No fairy shrimp.

- Sparse backswimmers (sub-order Heteroptera, family Notonectidae), few caddisfly larvae (Trichoptera), rare mayfly larvae (Ephemeroptera).

Virginia Divide Double Ponds. This view is looking more to the northwest across East Fork Green Creek canyon than photograph Virginia Divide Double Ponds 2016-09-08, #38.

October 4, 2022